A tale of two crises – metals in the year of covid-19

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

It’s been a tumultuous year for industrial metal markets, both the worst of times and the best of times.

Prices collapsed during the first three months of 2020 as first China, then the rest of the world, went into covid-19 lockdown, bringing manufacturing activity to a near standstill.

The subsequent rebound has been nothing short of spectacular with copper, bellwether of the pack, currently trading at its highest level since 2013.

Echoes of the Global Financial Crisis ten years ago ring loud. Once again, it seems, China has come to the rescue thanks to a massive stimulus package flowing down the metals-heavy channels of construction and infrastructure.

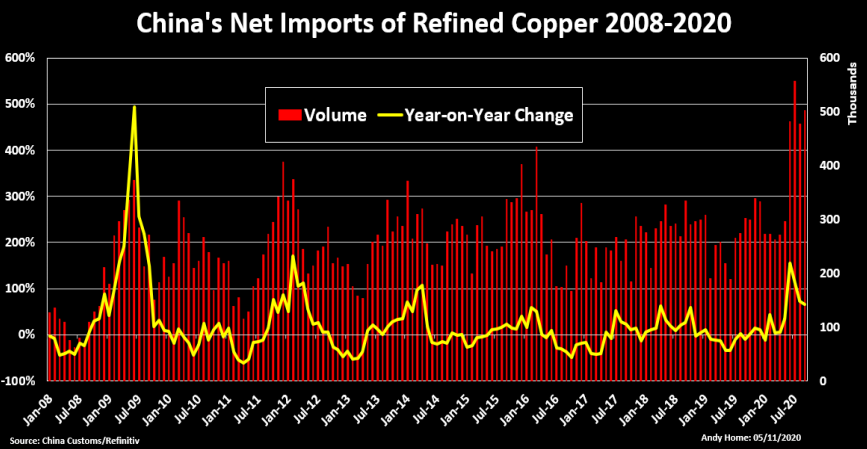

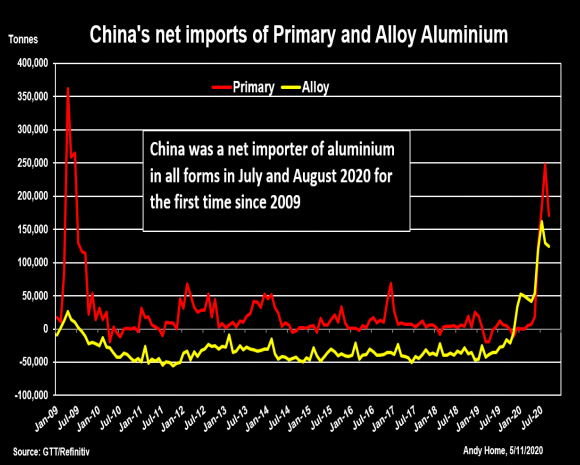

The country is importing record amounts of copper, effectively clearing the rest of the world’s surplus, and has turned net importer of aluminum for the first time since, you guessed it, 2009.

But there are two critical differences between now and then, and both of them are bullish.

Moreover, the last crisis is shaping how the world responds to the current crisis. The result is an acceleration of two mega-trends.

Not just a demand crisis

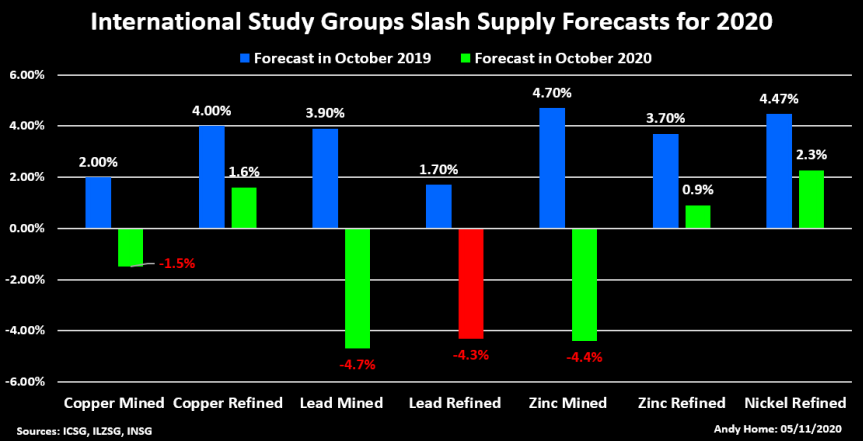

The first key difference between this year’s pandemic and the financial crisis is that it has impacted both metals demand and supply.

Lockdowns devastated demand in key end-use sectors such as automotive and aerospace production but they also caused multiple mine closures around the world.

Even harder hit has been the scrap supply chain as lockdowns froze both local collection networks and disrupted international flows

The lockdown lottery impacted each metal differently depending on its particular supply characteristics. Zinc and copper have been especially hard hit because of the severity of quarantine measures in important producer countries such as Peru.

The stress on raw material supply chains is evident in smelter treatment terms.

Spot copper treatment charges slumped to eight-year lows in the third quarter as smelters struggled to source enough mine concentrate.

The impact will spill over to 2021, judging by the annual benchmark just negotiated by Freeport McMoRan, the lowest since 2011.

Spot zinc treatment charges have slumped to under $100 per tonne, a long, long way off the 2020 benchmark of $299.75.

Even harder hit has been the scrap supply chain as lockdowns froze both local collection networks and disrupted international flows.

Scrap is the world’s biggest copper mine and plunging imports to China, historically the world’s largest buyer of sea-borne scrap, have been a major driver of the country’s record refined copper imports this year as users replaced secondary feeds with refined metal.

The simultaneous hit to both mine and scrap supply has helped mitigate the demand hit and left markets looking far healthier than they did in 2009, when the supply response was purely economic and slow to play out.

Not a credit crisis

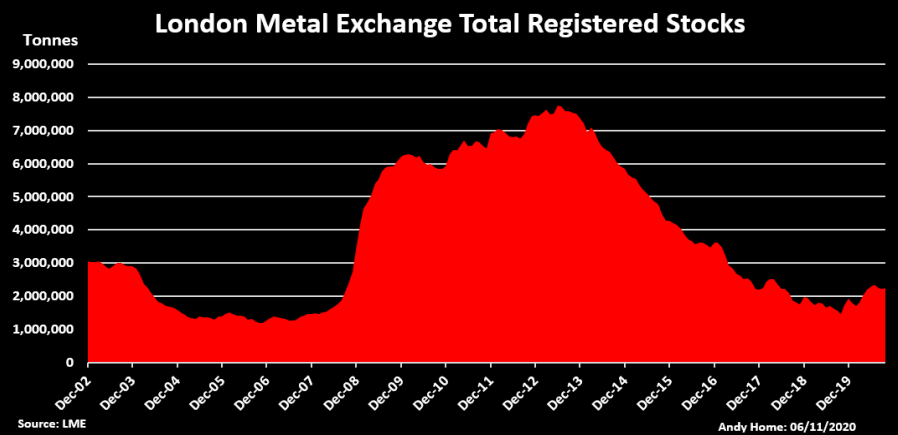

The second key difference between 2020 and 2009 is that this has not been a crisis of credit.

London Metal Exchange (LME) stocks mushroomed by 82% to more than six million tonnes in 2009 as the implosion of credit markets left the physical supply chain with no option other than to deliver surplus metal to the market of last resort.

As of the end of November this year LME stocks had risen by just 9%, or 180,000 tonnes, to 2.13 million.

Surplus metal in markets such as aluminum and zinc is sitting off-market thanks to easier financing conditions for both producers and physical traders.

LME aluminum stocks have actually fallen this year to the tune of 102,000 tonnes. Shadow LME aluminum stocks, by contrast, were up by 790,000 tonnes in October relative to February, which is when the exchange started publishing this new data series.

These “off-warrant” stocks are just the partially-visible tip of a bigger metal mountain being stored deeper in the statistical shadows.

The absence of exchange stock build has left market optics looking far more bullish than they were ten years ago.

Mega-trends

The last crisis was at heart a financial crisis and it got a financial fix. The European Commission has estimated that European countries had by 2015 spent almost 750 billion euros in bailing out 114 banks.

The populist anger that governments were saving Wall Street not Main Street fed the “Occupy” movement. It proved relatively short-lived. The last “occupation”, technically a reoccupation, was in the U.S. city of Portland in July 2013.

But the populist anger didn’t go away. Rather, it morphed into two contradictory forces that have shaped government responses to this year’s pandemic.

The poster-child for the first has been Greta Thunberg and the “Extinction Rebellion” movement, a youthful call for accelerated decarbonisation to save the planet from global climate catastrophe.

The message has been heard. The European Union, which responded to the last crisis by rolling bail-outs of weaker nations, has just agreed a 750-billion “green” recovery fund with the priority on electric vehicles, renewable power and low-carbon housing.

All three of the world’s economic super-powers – China, Europe and, after the election of Joe Biden, the United States – are now committed to carbon neutrality.

This is immensely positive for metals consumption since the green revolution is going to need a lot of metals, both new ones such as cobalt and lithium and old ones such as copper and tin.

The supply of all this metal, however, is going to be disrupted by the second mega-trend flowing from the populist anger that followed the last crisis.

It’s not just the United States looking to bring supply chains closer to home

Donald Trump has been the poster-boy for a surge in nationalist protectionism. “Tariff Man” has lived up to his name, particularly in the world of metals with U.S. tariffs on aluminum and steel disrupting trade flows.

The United States under the Obama administration was already moving towards a more critical approach to sourcing critical minerals, but the move to reduce foreign dependency has appreciably accelerated in the last four years.

Moreover, it’s not just the United States looking to bring supply chains closer to home.

The European Union is doing the same under the mantle of “strategic autonomy” with metals again at the forefront in the form of the European Battery Alliance and the Raw Materials Strategic Alliance. A carbon wall is due to be erected next year with significant implications for supplier nations with higher carbon footprints.

China is now committed to its “dual circulation” model with the emphasis on domestic resilience, meaning all three economic power-houses are on the same deglobalisation track.

The immediate impacts of covid-19 on metals will fade over the course of 2021. The longer-term impacts are here to stay.

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments