A new commodity squeeze could soon rival lumber’s recent historic shortage

Tin is in the grips of one of the longest-running squeezes ever seen in commodities markets, and there’s little sign of it letting up.

A relatively small market — used mainly for soldering in electronics — tin is often overshadowed by metals like copper and aluminum that are more widely used in manufacturing, infrastructure and the green-energy transition.

This year, though, tin has been red hot. Demand is booming and supply is sputtering, creating a chronic shortage of metal that’s been exacerbated by global logistics snarl-ups. Tin has surged more than 90% to all-time highs on the London Metal Exchange, while near-dated contracts have been trading above futures for almost an entire year on the LME, in a condition known as backwardation that’s a hallmark sign that spot demand is exceeding supply.

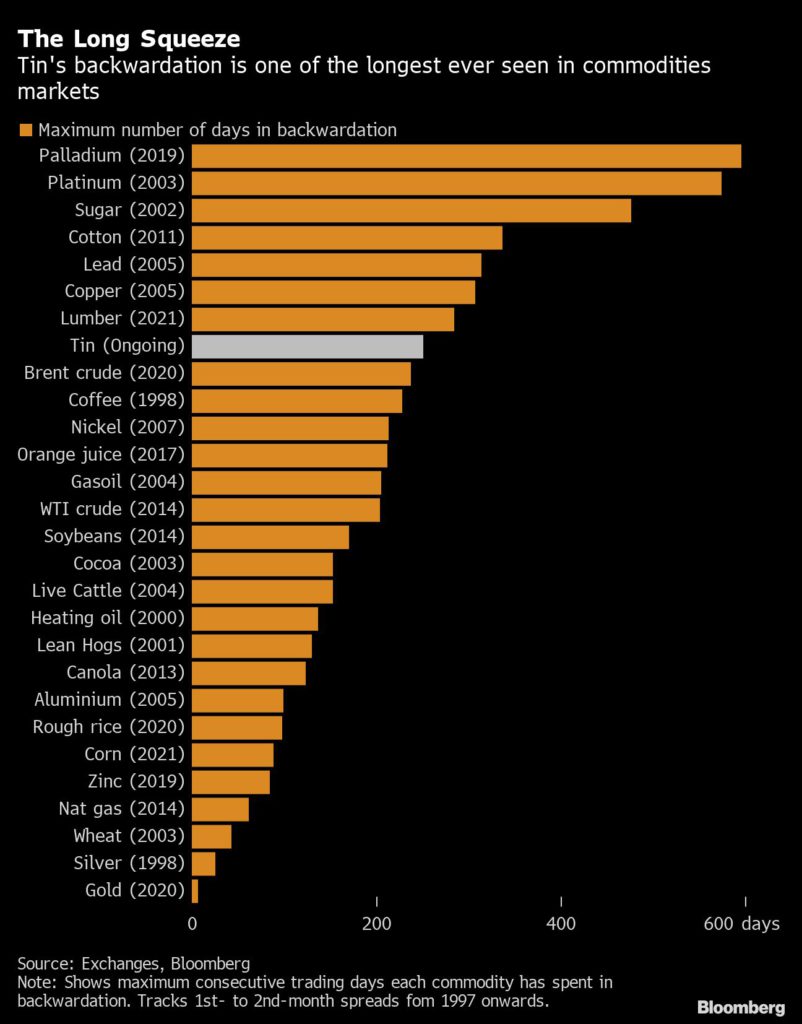

Front-month LME tin prices have now been trading at a premium to the second-month contract for more than 250 consecutive trading days, the longest-running backwardation in at least 24 years, according to data analyzed by Bloomberg. That’s longer than the most protracted backwardations seen in crude oil, nickel and coffee over the same period, and comes close to surpassing a historic 285-day squeeze in the lumber market that ended earlier this year.

Like lumber, tin’s supply-and-demand dynamics have been thoroughly upended by the pandemic. But while the backwardation in lumber ended in July as demand crested and production ramped up, it’s less clear where the supply relief will come from in the tin market.

Typically, backwardations tend to be fairly short-lived, as high spot prices encourage producers and traders to deliver cargoes into exchanges, replenishing supplies and helping to push spot prices back below futures. But the unrelenting surge in demand and logistical challenges in getting metal where it’s needed have created a rare long-running squeeze that’s dragged inventories lower and helped lift prices sharply higher.

“Normally you’ll get a big backwardation, and then it will take a bit of time, but producers or traders will deliver,” Tom Mulqueen, head of metals research at Amalgamated Metal Trading, said by phone from London. “This year’s just been so extreme, in terms of the inability to do that.”

While investors have piled into the tiny tin market during its rally to all-time highs, exchange data suggests that many have now taken profits on their positions. Yet the backwardation and broader supply tightness has endured, suggesting that the latest leg of the rally has been driven by core industrial users and real demand for metal.

The premiums that consumers pay over LME prices to obtain physical shipments of tin remain at sky-high levels, indicating that supply remains tight and record prices aren’t yet putting a dent in demand. And with the omicron Covid variant spreading rapidly, the challenges involved in producing metal and shipping it to consumers are in danger of getting worse.

The outlook for supply from major producer Myanmar is worsening as the country battles a new Covid-19 outbreak, while in Indonesia, top producer PT Timah’s output was down 49% in the first nine months of the year, according to the International Tin Association. On a positive note, Malaysia Smelting Corp is reportedly “looking into” ending a Covid-related halt on sales, which the ITA said may bring some relief to consumers.

But with demand still booming, inflows into LME warehouses could be few and far between, while dwindling inventories and tightening spreads on the Shanghai Futures Exchange suggest buyers in China will eagerly snap up any additional supply.

“I don’t think it’s permanent, and at some point it will normalize, but who knows how long that will take,” Mulqueen said. “I think it’s likely that things will settle down in the next year, but there’s very little give in the market at the moment.”

(By Mark Burton)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments