A forgotten gold rush hub is producing more than it has in a century

Deep under gum-tree lined paddocks in southern Australia that delivered a bullion bonanza in the 19th Century, the unexpected promise of a second gold rush is luring a new generation of prospectors from billionaires to global miners and weekend panhandlers.

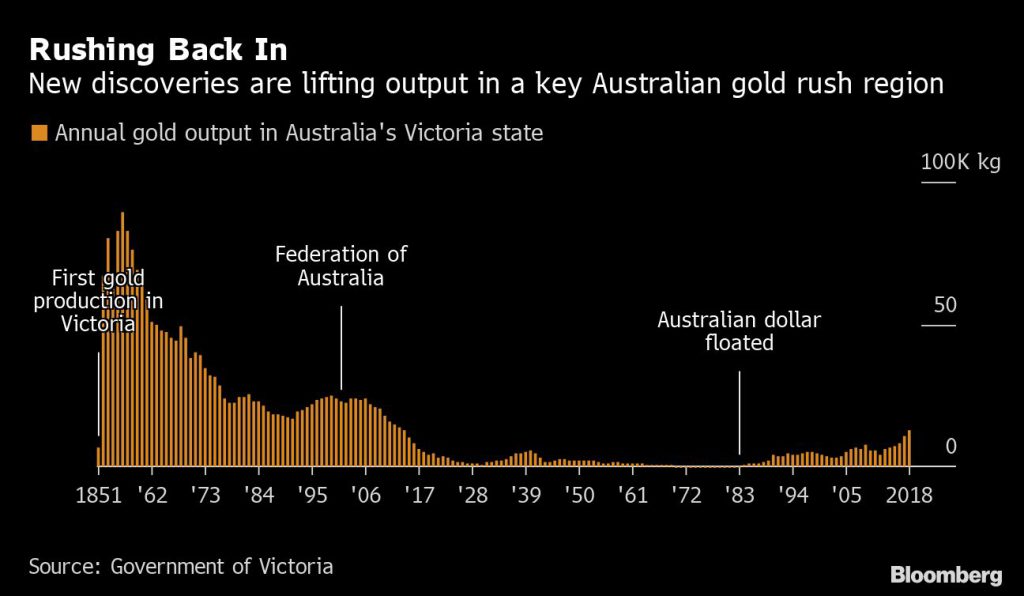

As prices soar, production in the goldfields of Victoria state is rising again and has already climbed to the highest since 1914 as mining companies dig deeper and new technology helps to uncover once hidden and richer deposits in a region that almost rivaled the Californian gold rush and was thought to have petered out decades ago.

“I’ve never seen anything like it in all my life — it’s like finding a safe underground”

David Baker, managing partner, Baker Steel Capital Managers LLP

“I’ve never seen anything like it in all my life — it’s like finding a safe underground,” David Baker, managing partner of gold investor Baker Steel Capital Managers LLP, and a visitor to mines for more than 30 years, said following a tour last month of Kirkland Lake Gold Ltd.’s Fosterville mine, the flagship for the region’s revival. “You don’t get better than that unless you can dig into Fort Knox.”

With Victoria’s state government forecasting there may be as much as another 80 million ounces buried underground in the region —about as much as was dug out during the initial gold rush from 1851 — major players are moving in, including Newmont Goldcorp Corp. and billionaire miner Gina Rinehart.

The region’s renaissance is also stoking hopes that new exploration of other historic global mining hubs could yet yield more riches.

A thirty minute drive east of Bendigo, a city of elegant Victorian-era civic buildings built with the proceeds of the first gold rush, Kirkland has transformed its underground mine into one of the world’s most profitable gold operations.

In a section of tunnel about 1.2 kilometers (0.75 miles) below surface, a thick diagonal white vein of gold-bearing quartz stretches across a face of dark gray rock, and fragments of ore scattered on the floor are studded with visible, glittering flecks of the metal.

Delving deeper into the earth to tap this different and more concentrated source of the metal has dramatically shifted Fosterville’s fortunes. The site was first mined for about a decade from 1894 and then sporadically over the next century, before an underground mine was opened in 2006.

“The better gold mines reveal themselves over time,” said Sydney-based Baker, a manager of the BakerSteel Precious Metal Fund, which holds about $450 million of assets, including Kirkland shares. Fosterville has shown “that it is actually a fantastic jewelry box, and one that’s only getting better,” he said.

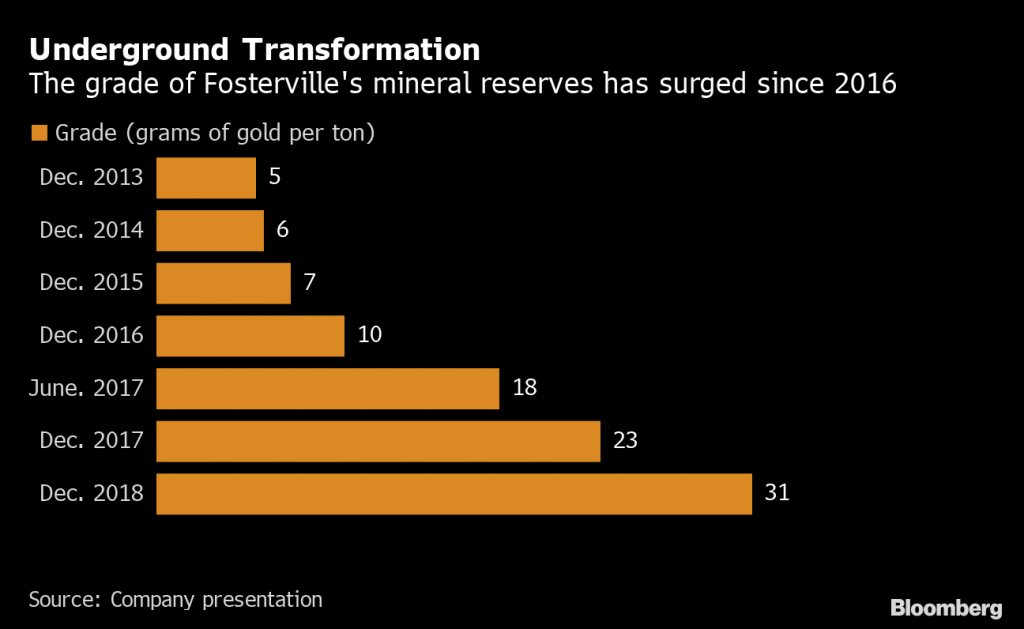

When valuing projects, miners estimate both the volume of remaining metal at an operation that’s economic to extract — the asset’s reserves — and the grade of the material, the amount of precious metal contained in each ton of excavated rock.

Fosterville’s reserve grade, which had hovered at around 5 grams of gold per ton, began to rise through 2014 and 2015, and then surged from the end of 2016, when Kirkland completed about a C$1 billion ($756 million) acquisition of the site’s previous owner.

At the end of last year, that grade was estimated at 31 grams a ton, among the highest in the world, and probably bettered only by Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.’s Hishikari operation in Japan, according to Quinton Hennigh, a veteran gold executive and geologist who helped to review the Australian site before Kirkland’s 2016 deal.

Improved grades have helped boost output to a record and spurred profits along with a rising gold price. Kirkland’s earnings from the operation more than doubled in the first half of 2019, according to a July filing.

Toronto-based Kirkland, which also operates mines in Canada, is growing confident it can unlock further high-grade zones underground at Fosterville, and already has had encouraging results close to the current mining area and as far as about four kilometers away.

“There’s something more broad and pervasive at play,” Ian Holland, Kirkland’s vice president for Australian operations said in an interview at the site. “Significant drilling programs will unlock that over time, that’s the truly exciting piece.”

Two historic mines in Victoria have resumed production since 2018, while Newmont has applied for an exploration tenement in the state

Others projects are also offering glimpses of potential. Gold Exploration Victoria Pty, a unit of Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting Pty, is partnering with explorer Catalyst Metals Ltd. on exploration around Bendigo that has shown early indications of high-grade gold finds.

Two historic mines in Victoria have resumed production since 2018, while Newmont has applied for an exploration tenement in the state, the company said in an emailed statement. Before the end of the year, Victoria’s government will launch an international tender for newly released exploration ground with similar geology to Fosterville, Minister for Resources Jaclyn Symes said.

Modern exploration techniques — like airborne electromagnetics and geochemistry — are helping miners globally to locate troves of metals buried deeper underground, and often beneath the cover of other rocks.

In the U.S., Nevada Exploration Inc. is using techniques including the sampling of groundwater to locate new gold deposits in a heartland of production. Companies including Australia’s Newcrest Mining Ltd. are also combing back over historic regions in Nevada.

Other established mining centers in the U.S. and Western Australia hold similar potential to deliver more gold from deeper underground, according to Hennigh, president of Novo Resources Corp. “There are certain gold camps that I see, where there are the telltale signs of there being a heck of a lot more,” he said. “There will be more discoveries without question.”

(By David Stringer)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments