A copper M&A frenzy masks big miners’ hesitation to build

In the dusty, treeless outback of Southern Australia, a brand new mining camp is home to a hundred workers, putting in 12-hour days, two weeks at a time. Dozens of trucks are scattered across the vast acreage, mounted with towering rigs drilling more than 2 kilometers (1.3 miles) underground. All are focused on the hunt for one of the world’s most coveted minerals: copper.

Oak Dam, discovered by BHP Group geologists in 2018, is a glimmer of hope for chief executive Mike Henry, who sees global copper demand doubling over the coming decades as the energy transition takes hold, and wants his company to produce more of it. The deposit is also a rarity — if all goes to plan, a new operation will be built here by the world’s largest miner, from scratch.

“Globally, there would be few companies conducting drilling campaigns of this scale, to this depth,” said Michael Fonti, BHP’s main exploration geologist at the site, pointing out a diagram of the cone-shaped deposit.

Fonti has spent more than two decades on sites much like this one, working most recently at the miner’s nearby Olympic Dam, a vast, challenging copper and uranium operation. But even for BHP — a $140 billion company which generated almost $12 billion in free cash flow in the last financial year — large, greenfield projects are scarce, and becoming more so. Deals, not discoveries, are grabbing the headlines.

Copper’s bull narrative, which helped prices hit an all-time high in May, is well understood. Electrification, wealthier populations and an expanding, energy-hungry technology sector are vast new sources of demand. An electric vehicle requires roughly three times the copper that goes into a conventional car, and the energy transition won’t happen without enough red metal for grids, batteries and chips.

This should all be prompting a surge in prospecting and digging, to ensure supply keeps up, especially as large, established mines age. It isn’t — and that risks making this much-needed metal punitively expensive.

Miners have been in spending purgatory for over a decade, atoning for the excesses of the last boom. For years, investors demanded generous returns, not production growth and certainly not risk. But now that diggers can open the purse strings again, high costs, slow permits and other hurdles are pushing the largest metal producers to buy — not build.

BHP, even with its effort to build out the copper belt of South Australia, is no exception.

Asked at its earnings briefing last month, Henry said the company was opportunistic about deals and not pursuing them at the expense of exploration, nor was BHP making a blanket decision on cost. There was no rule of thumb on buying or building, he said.

Still, in less than two years, BHP has bought copper and gold producer OZ Minerals for $6.4 billion, betting on South Australia’s copper province; tried and failed to buy peer Anglo American Plc for $49 billion, in large part for its South American copper mines; then in July agreed to buy copper miner Filo Corp. jointly with Lundin Mining Corp, a bet on a project in development on the Argentina/Chile border.

“Mining is cyclical, and a key factor driving the trend of buying over building is the point in the cycle,” said Campbell Cooper, a Melbourne-based advisor at Greenhill & Co., an investment bank. “Recent years have also seen an acceleration in the cost of building new mine capacity. Arguably that cost may not be fully reflected in equity valuations, making buying more attractive.”

Building from zero, in short, is both worryingly risky and unappealingly pricey.

No wonder, then, that only roughly a quarter of the sector’s sanctioned — or approved — projects between 2019 and 2023 were of the greenfield variety, according to analysts at Jefferies LLC. That’s down from more than half in the 2009 to 2013 period. The size of new projects is also shrinking.

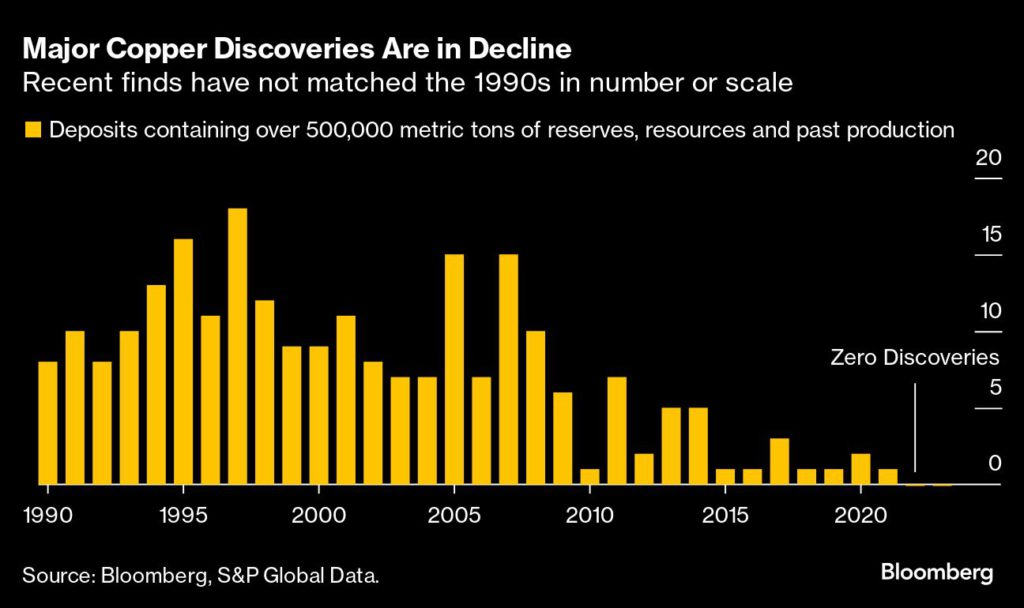

“There was a raft of copper discoveries in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s,” said BHP’s Fonti. “Everything being produced now is from that era of discoveries.” Escondida, the world’s largest copper mine, dates back to the late 1970s and early 1980s.

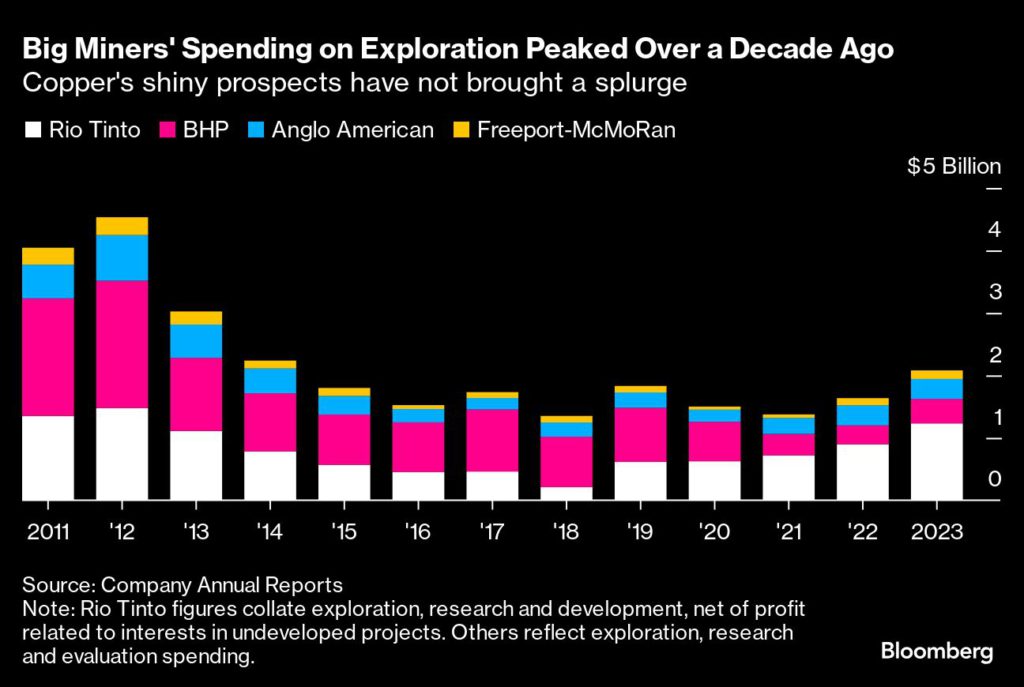

Of course, BHP has invested in development — it approved nearly $5 billion for its potash operation last year — but its exploration budget remains modest, even for copper. While it has nearly tripled its annual greenfield spending from the start of the decade to $124 million in the year to June, that compares to $324 million spent on greenfield exploration alone back in its 2012 financial year.

Peers follow similar patterns. Rio Tinto Group, which has not done large-scale deals of late, spent $300 million on greenfield exploration in 2023. Anglo American Plc and Freeport-McMoRan Inc have spent less. Glencore Plc does not detail exploration spending, but its focus has been on existing deposits in its portfolio.

“Ultimately the industry needs continual investment in exploration and new discoveries. M&A is important to put assets into the hands of the optimal owners, but will not materially increase overall industry supply,” said Sam Brodovcky, head of metals and mining M&A at Standard Chartered Plc. “And for key commodities such as copper, we need to increase supply not only to replenish depleting mines but also to keep up with growing demand as the world industrializes and transitions to clean energy.”

Henry says large players like BHP are well placed when it comes to adding supply. As greenfield risks increase, the industry’s behemoths can unlock more metal with the expansion of existing projects, thanks to large balance sheets and technical capability.

They are also betting on less risky exploration by supporting junior miners — as with BHP’s Xplor program, which provides modest funding with the potential for much more if prospecting is successful.

What is less clear is whether this will be enough to provide the metal the world needs.

Juniors, lower down the mining food chain, have long taken on much of the sector’s exploration risk. But that proportion is now increasing just as investment in smaller outfits falls.

“We’ve got to a point where we’re quite reliant on juniors to explore. It’s very difficult seeing that continuing if they’re not getting the equity that they need,” said Sandra Occhipinti, a geologist and researcher at Australia’s national science agency, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

Richard Schodde, a veteran geologist and expert on South Australia’s copper belt, puts the number of discoveries made each year at only a handful. He describes BHP’s lucky strike at Oak Dam in 2018 “was probably the most spectacular” of recent years.

Price is clearly one reason holding back the splurge that could change that. Copper has enjoyed a bull run on fears of supply disruption and hopes of soaring green demand. Prices topped $11,000 a ton earlier this year. But the global economy is faltering and copper needs to reach $12,000 a ton — a near-30% jump on current prices — to incentivize large-scale investments in new mines, according to Olivia Markham, who co-manages the BlackRock World Mining Fund.

Copper’s improvement since the price trough of 2020 has not been enough. Costs are rising too fast as exploration teams need go deeper, into more technically challenging deposits or into less desirable regions.

Take Oak Dam, where the bottom of the deposit is some four kilometers underground — depths where heat from the earth’s core starts to become a problem. Or even Olympic Dam’s next phase of exploration, Olympic Dam Deeps. BHP’s recently acquired Filo asset in South America, meanwhile, sits some 5,000 meters above sea level, where the air is so thin helicopters struggle to hover.

“Once upon a time you could just kick rocks. It’s not for the faint-hearted — and only one exploration campaign out of a thousand results in a discovery,” says Karol Czarnota, a director at Geoscience Australia, a government agency set up to encourage mining. Oak Dam was found using some of its data.

One area of good news is technology. New gadgets and better geological information are allowing even the reassessment of existing repositories of data. Core libraries around Australia, for example, hold over 100 million meters of rocks from drilling campaigns of past booms, free for geologists looking for mineralization missed by others.

But even at Oak Dam, a deposit that was almost missed until new geophysics techniques could unlock it, that cheer is tempered. The slow pace of mine development means a final investment decision will not come until 2027 at the earliest. Copper production will still be years away.

(By Paul-Alain Hunt)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments

Doug Lomow

Great publication. I would appreciate receiving your publication in print. Thanks