A copper bug asks ‘who got copper’?

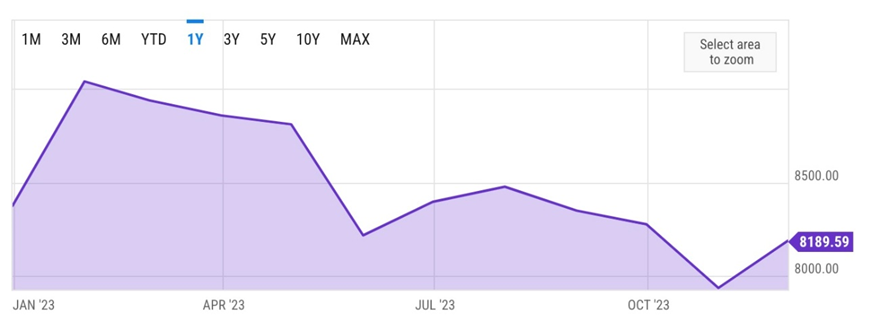

The copper price has climbed to within spitting distance of 4 bucks a pound, on news that the Federal Reserve’s interest rate-hiking cycle is likely over and a weakened US$.

Increased demand for copper to a loosening of monetary conditions is one reason to be bullish, but copper bugs like us at AOTH know the real copper price driver is under-supply.

To illustrate: the copper price hit a near 10-week high at the end of November due to the surprise closure of First Quantum Minerals’ Cobre Panama, one of the world’s largest copper mines.

The copper market narrative has been one of shrinking supply in the face of surging demand, not only due to electrification and decarbonization — EVs use four times as much copper as regular cars and trucks for example — but all the other applications for copper including in construction, power generation and telecommunications.

In February, CNBC reported that “a copper deficit is set to inundate global markets throughout 2023, fueled by increasingly challenged South American supply streams and higher demand pressures.”

Wood Mackenzie is forecasting major deficits in copper to 2030. Most of the world’s copper are located in Chile and Peru, areas that are increasingly volatile from a political and social perspective.

Copper mine failures

For example Peru, which accounts for 10% of world copper supply, has been racked by protests since its former president, Pedro Castillo, was ousted a year ago.

A strike is currently underway at the Las Bambas mine owned by China’s MMG Ltd.

Exposing the copper surplus myth

At the same time, Panama’s top court ruled that First Quantum Minerals’ contract to operate the Cobre Panama mine is unconstitutional. The government then ordered First Quantum to end operations at its $10-billion copper mine, which has only been operating for four years.

Between those two mines, the copper industry has lost nearly 600,000 tonnes of production.

Resource nationalism in Panama has become a real problem for existing and potential mines. On Dec. 18 it was reported that the Panamanian Ministry of Commerce and Industry canceled Orla Mining’s requests for extending three mining concessions at its Cerro Quema project.

The news release went on to say, “The project includes a pre-feasibility-stage, open-pit, heap leach gold project, a copper-gold sulphide resource, and various exploration targets. The Company believes that the Cerro Quema Project could be an important social and economic contributor to the host communities. To date, the Company has invested over US$120 million in Panama.”

Meanwhile Chile, the largest red-metal producer, accounting for 27% of global supply, recorded a y/y decline of 7% in November.

“Overall we believe Chile will likely produce less copper from 2023 to 2025,” Goldman Sachs wrote in a note.

Chile’s copper production has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north, where most of the copper mines are. Read more about this in the section below on global warming.

State-owned copper miner Codelco expects production this year to fall up to 7% after plummeting in 2022. Last year, production dropped from 1.753 million tonnes in 2021 to 1.553Mt. In February, the company saw the weakest monthly result since 2017, with output falling 12%.

Bloomberg notes Codelco is striving “to tap new areas of its aging deposits after decades of underinvestment.”

Incentive price too low

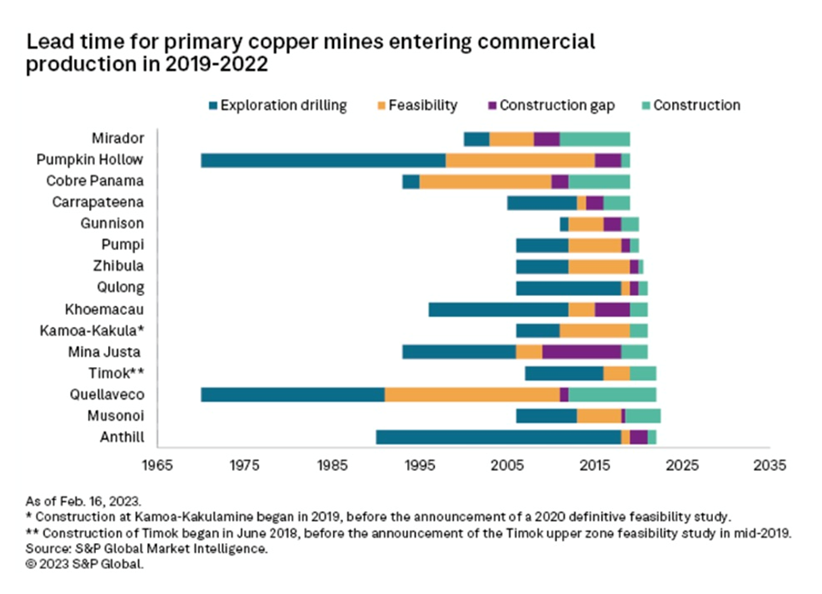

One of the biggest problems is there aren’t enough new mines. Over the past decade, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling 80% since 2010.

Truth is, today’s copper price is too low for new mines to be economical. Incentive pricing in the copper industry is considered to be US$11,000 a tonne — much higher than the current ~$8,200/t.

In fact, it’s probably much higher than that.

Mining magnate Robert Friedland says copper prices have to nearly double to prompt mining companies to build new copper mines whose capex usually runs into the billions. He said forecasts of copper prices reaching $9,000 a tonne next year aren’t enough to incentivize the industry especially in Latin America, which has become more risky.

“We probably need about $15,000 a ton, stable for a long period of time, before the industry can really gear up and build those giant mines,” the Ivanhoe Mines founder and executive co-chairman said Friday in an interview on Bloomberg Television.

Friedland also warns of a copper “train wreck” if supply can’t keep up, stating earlier this year that prices could jump 10-fold, and cause volatility in the copper supply chain to spike.

Friedland said a combination of factors suggests supply won’t keep pace with demand, including the fact that deposits are getting more expensive and trickier to find, that funding is scarce, and societies have yet to grasp mining’s role in the shift to fossil fuels. (Bloomberg, June 26, 2023)

“When metals are required, the prices go crazy and nobody’s willing to sell them,” he said. “We’re heading into that sort of situation.”

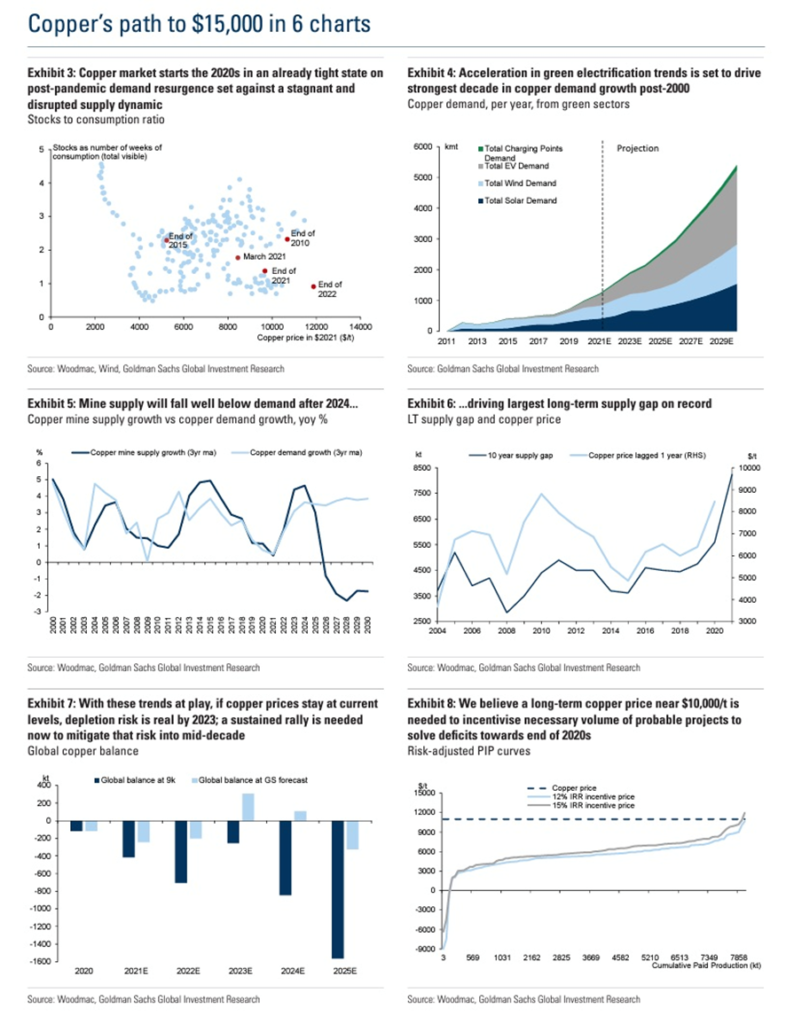

A 2021 report by Goldman Sachs titled ‘Copper is the new oil’ encapsulates the situation Friedman describes quite well:

Copper on a necessary path to $15,000. To capture the precise dynamics of this process we construct long-run models of scrap supply and substitution, as well as extend our balance out to 2030. The immediate conclusion is that current copper prices ($9,000/t) are too low to prevent a near-term risk of inventory depletion, while our current long-term copper ($8,200/t) is not high enough to incentivise enough greenfield projects to solve the long-term gap. If copper remains at $9,000/t through the next two years, then we estimate the resultant deficits would generate a depletion of market inventories by early 2023. Based on our scrap and demand modelling, we believe that the most probable path for copper price from here – that both avoids depletion risk and as well as a sharp surplus swing – is to trend into the mid-teens by mid-decade.

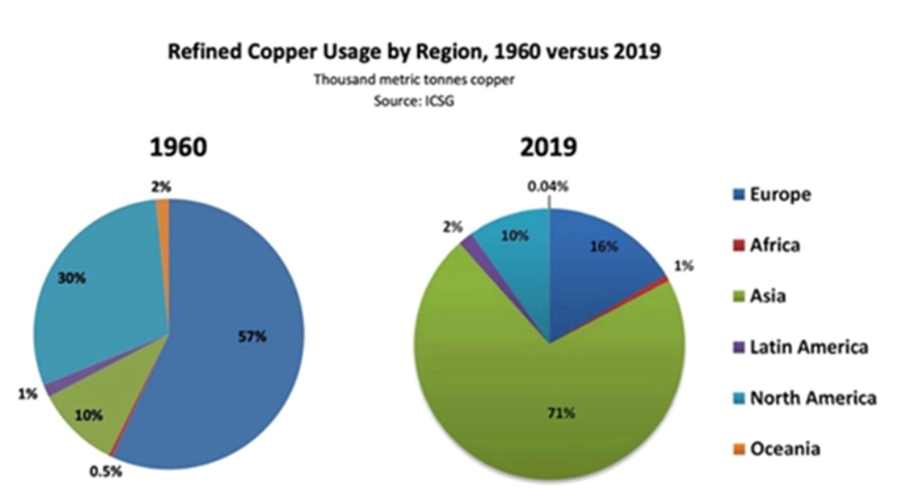

Asia has locked up new copper supply

As we’ve reported, 80% of the foreseeable copper supply is coming from just five mines, but four out of five have offtake agreements with non-Western buyers. That supply is locked up.

The mines are Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC. (by shutting down Cobre Panama, the industry just lost an annual 400,000 tonnes).

In the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Escondida and Quebrada Blanca are both partially owned by Japanese companies — one can assume that a corresponding percentage of production will be going there.

Analysts do not concern themselves with “who” owns the copper, their only concern is with the amount of global supply. Unfortunately, where it’s going – mostly China, South Korea and Japan – means it’s hardly global supply. Fact is, the West has almost no offtake agreements in place for 80% of the world’s future copper supply.

It’s been previously stated that we need to find 6 million more tonnes of copper, 1 million per year of new copper production if we want to alleviate the deficit — the equivalent production of one Escondida mine each year — but only one of the five mines, Kamoa, has the capability of producing close to that much copper. But Kamoa’s production is going to China.

At AOTH we make a clear distinction between global copper supply and the global copper market. Mined copper that is locked up by offtake agreements should not rightly be lumped in with global supply, because it will never reach the United States, Canada or Europe. Instead, this copper will go straight to smelters in China for use in Chinese industry, to South Korean smelters for South Korean industry, and to Japanese smelters for Japanese industry.

Mined out

Robert Friedland says the average age of the world’s top 10 mines is 95 years.

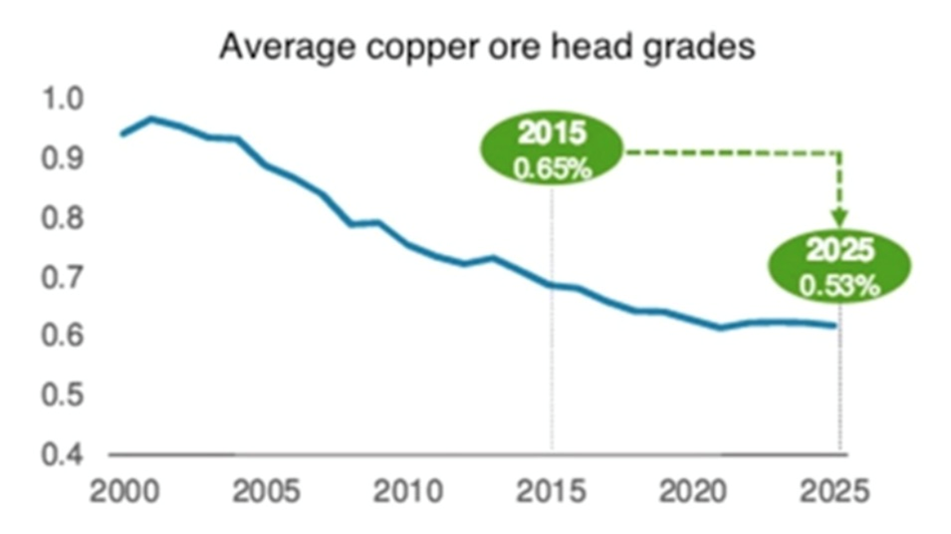

Operating copper mines are facing dwindling supplies of easy-to-access ore, meaning miners must dig deeper; the increased excavation obviously costs more.

Several large copper mines have mined out all the ore in open pits and are heading underground for the higher-grade, but more expensive to extract material. One example is Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia, which began underground operations in May.

A mine plan is based on the “cut-off grade”, which is the minimum grade needed to make a unit of rock economic to extract at a given price. Any ore below this grade stays in the ground. When metal prices rise, the mining company makes more per tonne, so it is able to “lower the cut-off grade” and still make a profit. It’s essentially turning what was previously waste rock at old pricing into mineable ore at the new prices.

Average copper ore head grades have fallen substantially since 2015 and will continue to trend lower as the chart below shows.

Global warming

We know that Chile, the world’s biggest copper producer, has problems with water and is having to desalinate seawater used for mining copper in the country’s arid north. Cochilco, the country’s copper commission, estimates the use of desalination by mining to increase 156% through 2030, with 90% of the desalinated seawater used for copper processing.

Severe droughts are drying up rivers and reservoirs vital for production of zero-emission hydropower in several countries.

As global warming makes already scarce water and mineral resources more difficult and expensive to access, the protection of existing mines and the hunt for new deposits will intensify, resulting in potentially lower production, higher operating costs and conflicts between both water and land users.

With much of the world currently experiencing droughts, and the effects of warming occurring more frequently and powerfully, it seems to me that there’s a very real risk to future metals output.

“Disruptions at copper mines caused by extreme weather and labour issues, for example, are predicted to worsen, likely affecting a record 1.6 million tonnes of production this year, Goldman Sachs analysts say, a headache for companies hunting for minerals to power the green energy boom as their deposits get depleted. ” (Reuters, Jan. 31, 2023)

Indeed, to achieve net-zero emissions targets, annual copper demand is likely to double to 50 million tonnes by 2035, according to a study by S&P Global. How much red metal actually becomes available is seriously in doubt, as we have outlined in the sections above.

Remember, electric vehicles use about four times as much copper as gas-powered cars and trucks, millions of feet of copper wiring are needed to build smart grids that can handle electricity produced by renewable power, and solar and wind farms require more copper per unit of power than coal- and natural gas-fired power stations.

India

Nearly 600,000 tonnes of production has been stripped out of the global copper market due to the strike at Las Bambas in Peru and the government-mandated closure of Cobre Panama.

But wait, this isn’t the end of the under-supply story. New information uncovered by AOTH in recent days shows that India and China will be taking loads more copper that will, once again, make it unavailable for Western usage, tightening the market further and ratcheting up prices.

According to a Bloomberg story last week, a billionaire-owned copper plant in India is expected to come online in March, 2024. The Kutch Copper Ltd. facility will have an initial annual capacity of 500,000 tonnes, but could require up to 1 million tonnes of overseas copper concentrate in its first year of operation.

Legal proceedings are also underway to re-open a 400,000-tonne copper plant in Tamil Nadu run by Vedanta Ltd.

Between the two facilities, that’s 1.4 million tonnes of copper concentrate that will have to be shipped from other countries — 90% of India’s ore requirements are imported from South America.

In fact, the country’s concentrate imports could grow to as much as 2 million tonnes in 2024, from 1.3Mt estimated this year, “because of expanding smelting capacity in China and India,” a commodity strategist at ANZ Banking Group quoted by Bloomberg said.

As for what is behind the need for so much copper, ICRA Ltd., an arm of Moody’s Investor Service, said India’s refined copper consumption is expected to grow by 11%, driven by the Indian government’s spending on infrastructure, and the country’s transition to renewable energy. The government plans to grow the economy to US$5 trillion by 2025.

Blackridge Research & Consulting lists eight megaprojects to watch for in India this year. They are the Narvada Valley Development Project; the Navi Mumbai International Airport; the Chenab River Railway Bridge, the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor, the Bharatmala Project, the Mumbai Trans- Harbour Link, the Inland Waterways Development Project, and the Zoji-la and Z-Morph Tunnel Project. Read more about them here

In a September note, ANZ commodity strategists Daniel Hynes and Soni Kumari said Indian copper demand will rise 40% on 2022 to 1.5Mt by 2025.

Areas of growth include an expansion of India’s manufacturing and infrastructure sectors; electric vehicles, including the country’s push to electrify its bus network; and renewables.

“With a goal of achieving 500GW of renewable capacity by 2030, a conservative estimate suggests 40% (400–500kt) of additional copper demand will come from the solar and wind sectors by 2030,” Hynes and Kumari wrote, via Stockhead.

China

Part of the reason for the copper price being range-bound this year around $3.60 a pound is on account of less demand from China due to its weaker economy.

For years China’s booming property sector fueled demand for copper and other raw materials. Rising home prices were a reason for Chinese to invest their savings in property. But this widened the wealth gap between those who owned property and those who didn’t, prompting China’s President Xi Jinping to act. As BNN Bloomberg explains, When Xi made his move to tighten property regulation, it set off a chain of events that have become a substantial drag on growth and a major challenge to his government. Home prices began falling, developers started defaulting and people got angry.

In August, regulators in China announced measures to support households and shore up the property sector. This included looser down payment requirements and reductions to mortgage rates. State banks also began cutting deposit rates.

Reuters reported on Friday that China’s weak property sector and retail sales are keeping stimulus calls alive.

As for what China’s economic woes mean for copper, because the country is the largest red-metal consumer, it’s bound to have an effect.

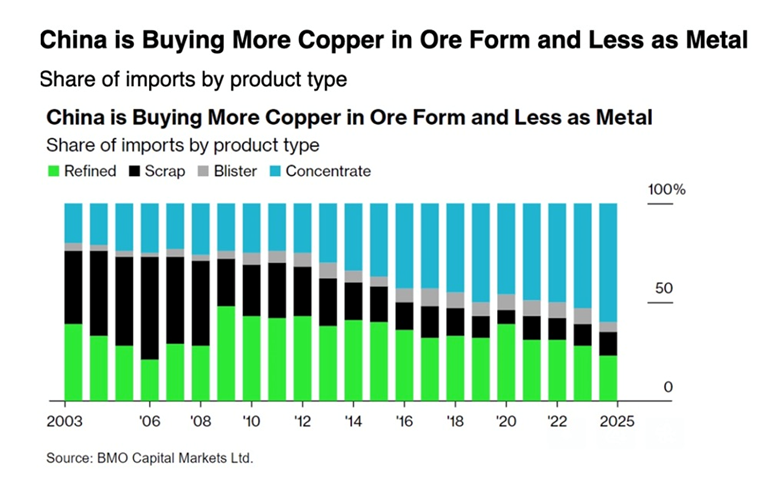

In August, Reuters metals columnist Andy Homes wrote, “China’s imports of refined copper fell to a four-year low in the first six months of 2023, underlining the sense of stalled momentum in the world’s manufacturing powerhouse… However, the continued strength of copper raw material imports is translating into record domestic refined metal production, a structural shift towards self-sufficiency…”

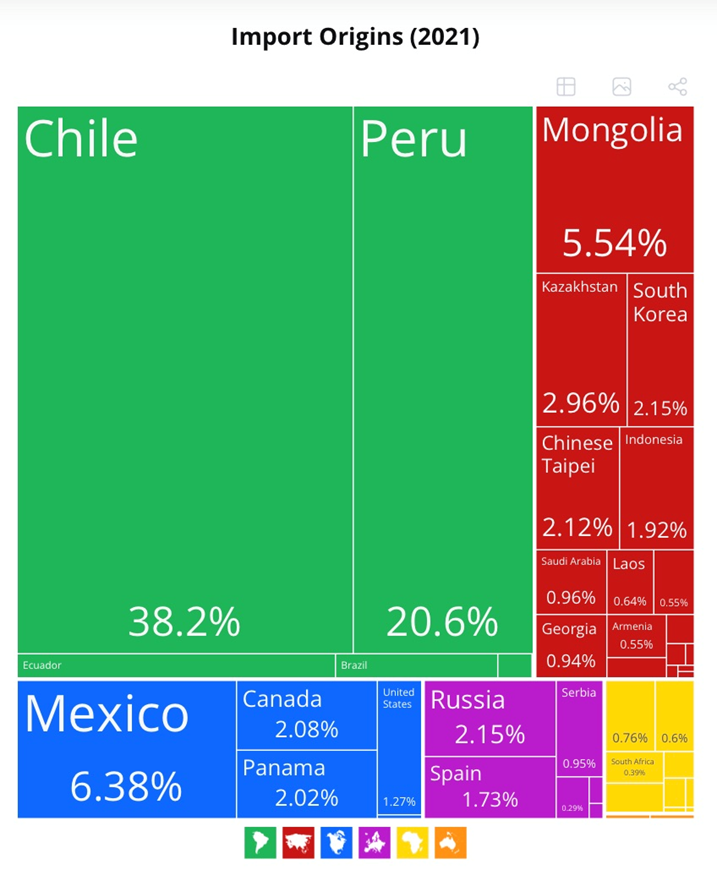

China imports copper primarily from Chile, Peru, Mexico, Mongolia and Kazakhstan.

A research report put out this year says China’s local copper mines are mainly small and medium sized, and the grade of copper ore is less than one-third of the grade of ore from the world’s major copper producing countries, so China is heavily dependent on imports of copper ore, with China’s copper ore import dependence exceeding 90% in 2021.

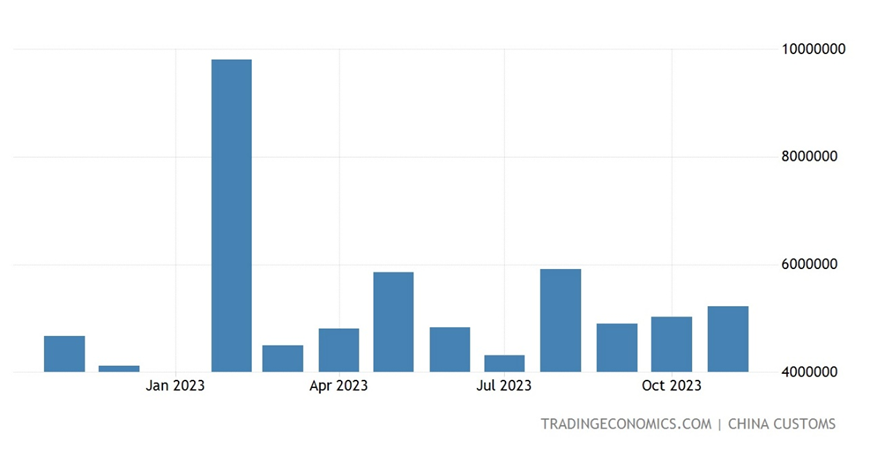

Although China’s January to October copper imports slid 6.7% on strong domestic production, October imports jumped 23.7%, the highest in 10 months. Nasdaq reports Imports of unwrought copper and copper products, used widely in the construction, transport and power sectors, totalled 500,168 metric tons, the highest since last December, data from the General Administration of Customs showed. The data includes anode, refined, alloy and semi-finished copper.

Meanwhile, China’s domestic copper inventories have declined in recent months, providing more impetus for overseas shippers.

In November, BNN Bloomberg said copper concentrates from Australia were headed to China, amid thawing relations between the two countries. The 11,000-ton consignment was the first such shipment since the country halted imports from Down Under three years ago. A second shipment was planned for the following week.

According to Trading Economics, China’s dollar-value imports of copper ores and concentrate increased to US$5.221 million in November, compared to $5.028 million in October.

China is going to continue taking a lot of refined copper and wants to switch to importing a lot more unrefined ore.

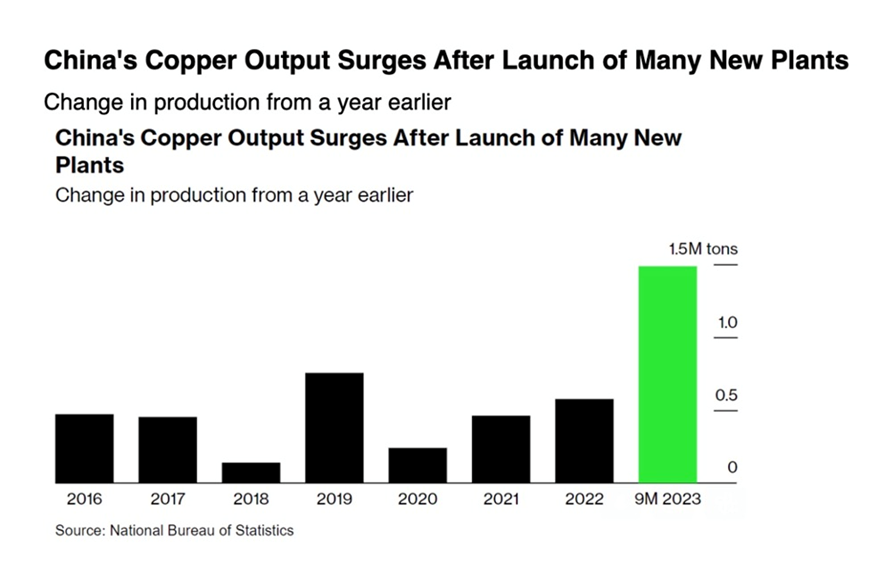

To ensure self-sufficiency, China is expanding its network of copper smelters, meaning it will start to import much more copper ore for processing domestically. According to CRU, the country is expected to account for about 45% of global refined copper output this year.

Data from Fastmarkets showed there is expected to be a net increase of at least 3.4 million tonnes per year of new copper smelting capacity. For example, China’s largest private copper producer Nanfang Nonferrous was due to bring a major new smelter to production by October, more than doubling its capacity, Reuters said.

China is already home to half the world’s capacity to make copper cathodes. A net increase of 3 million tpy of primary copper smelting capacity would translate to new demand for roughly 12 million tpy of copper concentrates.

China’s new copper smelting capacity is expected to turn China into a net copper exporter by 2025 or ‘26. With so many smelters requiring copper concentrate, the market for concentrate is tightening.

Miners pay smelters a fee to process copper concentrate into refined metal, to offset the cost of the ore. TCRCs (treatment and refining charges) fall when tight concentrate supplies squeeze smelters’ profit margins.

A recent BMO Metals Brief states “Spot TCRCs are now at the lowest level since March.”

Global miners have reached agreements with Chinese smelters for lower TCRCs, the first drop in three years, Reuters said.

Conclusion

China’s is going to continue taking a lot of refined copper and wants to switch to importing much more unrefined ore. China is building out its network of copper smelters, just like it did for iron ore, cobalt, rare earths, lithium, etc. There is no doubt in my mind that China is aiming to become the swing copper producer, and the world’s largest copper exporter, giving it the strongest influence on the copper market. It would effectively become a price maker, not a price taker.

This is yet another example of the global copper market tightening and supporting higher prices.

India overtook Japan as the world’s third-largest carmaker last year. According to ANZ, each additional million dollars in Indian GDP equates to 300 kg of growth in copper demand.

Between two new copper smelters opening up next year, India will need 1.4 million tonnes of copper concentrate that will have to be shipped from other countries, almost exclusively from South America.

But the two leading copper producers, Chile and Peru, are having problems meeting production targets due to a combination of global warming, declining ore grades (Chile) and social unrest (Peru).

In Panama, widespread opposition to First Quantum Minerals’ Cobre Panama mine prompted the government to shut it down. First Quantum is taking the country to the International Court of Arbitration to obtain damages for the forced closure.

Between the strike at Las Bambas in Peru and the shutdown of Cobre Panama, close to 600,000 tonnes has been removed from global copper supply. Now add the 1.4 million tonnes of copper required by India to be used by two new copper smelters opening next year. The result is 2 million tonnes of copper that is not coming to the West and should therefore be excluded from global supply.

The Biden administration’s three signature pieces of legislation — the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act — are costing trillions.

Remember though, that most of this promised money has yet to be spent. When the promises finally translate to shovels in the ground, that will mean thousands of tonnes of additional copper demand, for things like smart grids, nuclear power plants, electric vehicles and EV charging station, and blacktop infrastructure.

Where are we going to find the copper?

Copper is already facing major supply challenges, including strikes, resource nationalism, global warming (droughts, water shortages), declining ore grades, depleted orebodies, a lack of new mines, and regulatory delays in building new ones.

Moreover, the current copper price is too low to incentivize new mines.

Asian countries are switching to ore imports as they expand refinery/ smelting capability. This does not bode well for Western copper supplies. Remember, for the foreseeable future, copper supply is 80% concentrated in just five mines, all of which have major off-take agreements with South Korea, Japan or China. For instance, 100% of the massive Kamoa mine’s offtake will go to China.

As for producing copper domestically, the Canadian and US governments haven’t made it any easier for copper mining companies. About half of America’s scrap metal is sent overseas for processing because the country doesn’t have enough smelters. The Biden administration has prevented or stood in the way of new mining properties in Minnesota, Arizona and Alaska. Even when mines are green-lighted, in North America it can take up to 20 years to get from discovery to production.

Commodity analyst predictions are usually wrong about copper supply, often predicting a glut in the market for the ubiquitous metal used in everything from piping and wiring in houses, to electrical transmission lines to components of electric vehicles.

Every year there are between 800,000 and 1 million tonnes of copper that fails to make it from mine to market. This buffer is never accounted for in analysts’ supply predictions. But we at AOTH know it’s real. When we add this “missing” copper to the 2 million tonnes of copper that has already disappeared from the global copper market, we get between 2.8 and 3 million tonnes of under-supply, the equivalent of roughly 13% of global copper supply. (2022’s mine supply = 22Mt)

Wood Mackenzie analysts estimate a 6-million-ton shortfall by next decade, meaning six Escondida-sized mines would need to come online within that period – this is 100% NOT going to happen, not even close.

A report by another consultancy, McKinsey, found that electrification is projected to increase annual copper demand to 36.6 million tonnes by 2031, with supply projections offering a pathway to 30.1Mt, leaving 6.5Mt of capacity to be found.

I pose the question again: Where are we going to find the copper?

At $8,200 per tonne copper, there just isn’t the incentive to build new mines. Robert Friedland and Goldman Sachs think the incentive price isn’t $9,000 per tonne, nor $11,000, but $15,000, and we agree.

It is likely going to take a major out-of-stock event for the copper market to re-calibrate supply and demand with a price that both avoids depletion risk and a sharp surplus swing. Goldman Sachs forecasted in 2021 that the copper price (in tonnes) will reach the mid-teens by mid-decade. I’d say that’s on track. And it may not be a gradual uptick but a sudden increase. That will be an unpleasant surprise to end users but not to me, a copper bug who has been tracking supply since 2008.

(By Richard Mills)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments