A burning question for coal’s brightest star

If India is such a bright hope for global coal demand, why can’t investors see it?

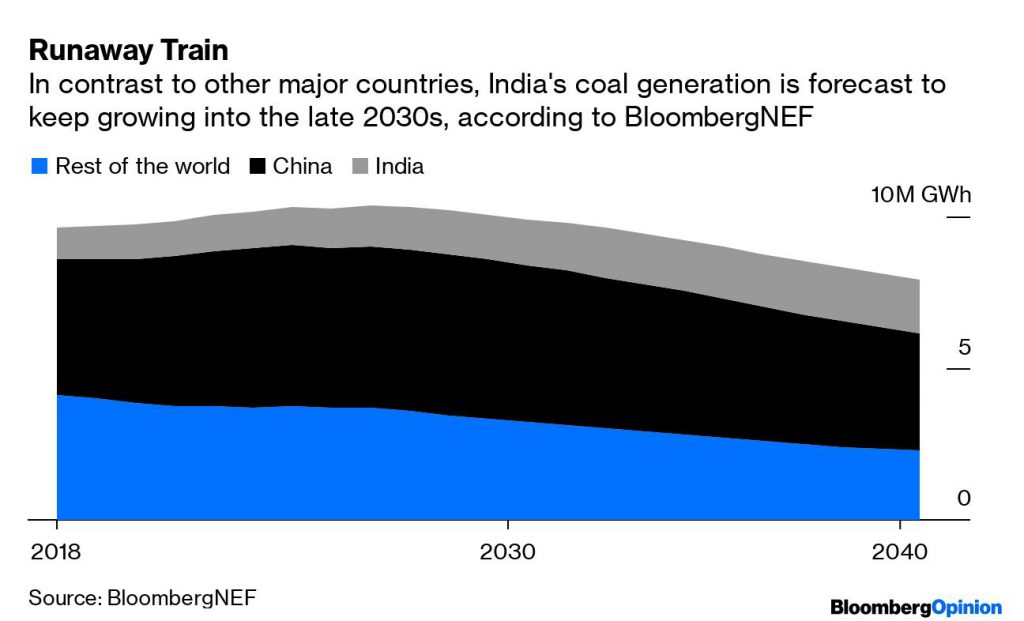

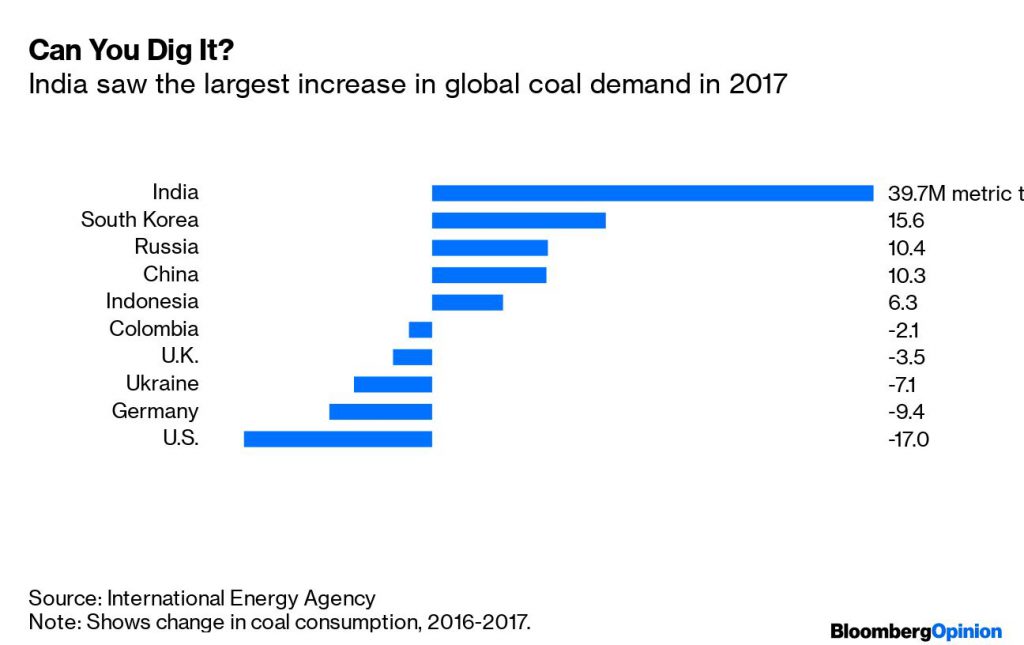

The country will experience the largest increase in coal burning through 2023, according to the International Energy Agency, with a 3.9% annual pace of growth that should be enough to offset falling consumption in developed countries. BloombergNEF, whose forecasts tend to be less bullish than the IEA’s on fossil fuel demand, is not far behind: Coal-fired generation will increase about 48% by 2030 to hit 1,512 terawatt-hours, more than all of Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.

The curious thing is that when you look at the Indian power sector, there are few signs it’s on the brink of a boom. Quite the opposite: As many as 65 gigawatts of the 90GW of private-sector generators connected in India are under financial stress, according to a parliamentary report last year. As my colleague Andy Mukherjee has written, the resulting 1.8 trillion rupees ($26 billion) in bad loans is contributing to a nonperforming asset crisis that risks undermining the Indian financial system.

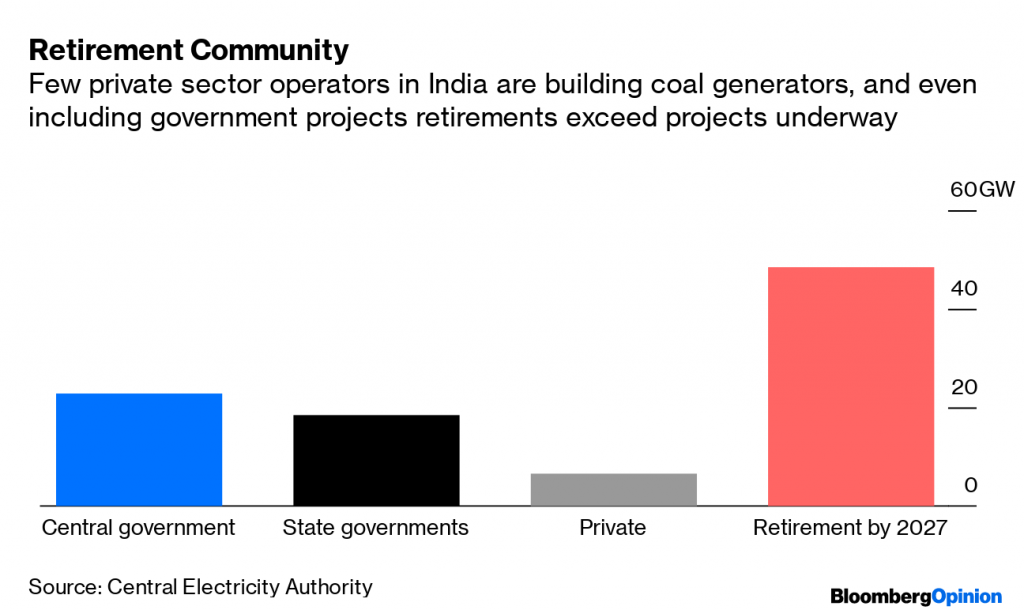

Furthermore, activity to increase coal-fired generation is overwhelmingly dependent on state support. Out of 48GW of coal generators planned to be built by 2027 under the country’s current electricity plan, just 14% is being developed by the private sector; a matching 48GW of generation is already slated for retirement by the same date.

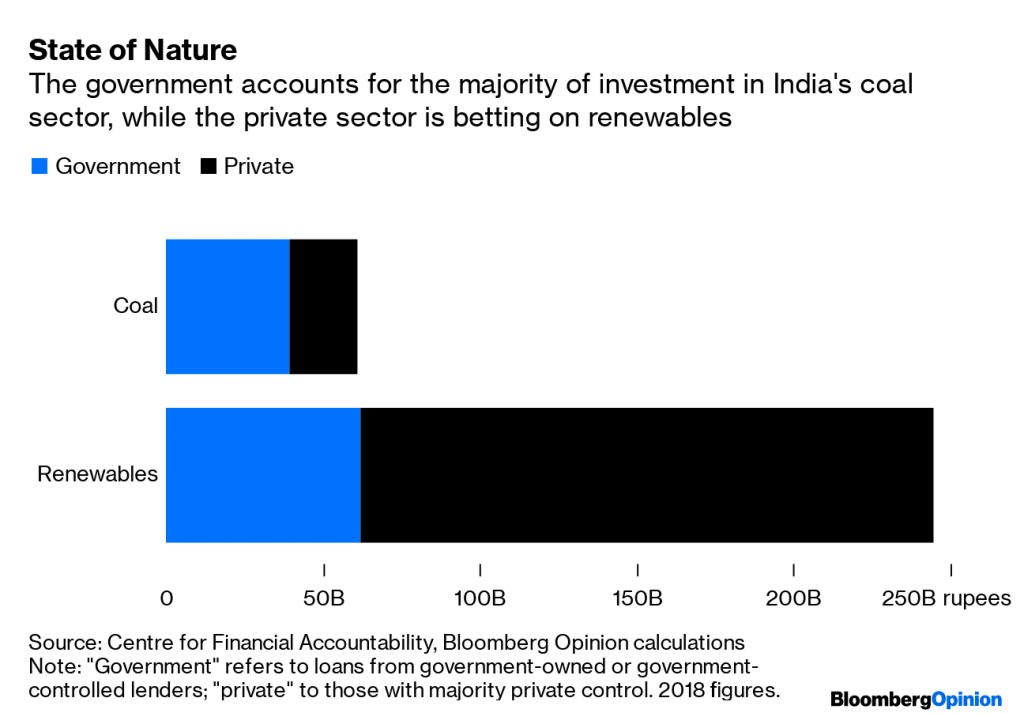

Even that modest level of private investment appears to be retreating now, according to a report published Friday by the Centre for Financial Accountability, a Delhi-based group pushing for better standards of development finance. Lending to coal-fired power fell 90% in 2018, to 60 billion rupees from 608 billion rupees the previous year, the CFA said. The vast majority of that total was refinancing of existing plants: Just 12 billion rupees was dedicated to new generation, all of it to just one state-backed plant in Uttar Pradesh.

If you still think wind and solar are the energy sectors most dependent on state support, you’ve not been paying attention to how the landscape has changed. In India, 65% of funding to coal-fired projects in 2018 came from government-controlled institutions, whereas three-quarters of loans to renewables came from the private sector, according to the CFA. Even a sixfold increase in renewables subsidies to 150 billion rupees in 2018 left that sector shy of the 160 billion rupees directly supporting the coal mining and generation sector, according to a separate report last year.

There are several reasons that India’s coal sector is struggling. The vast expansion of generation over the past decade has left the country oversupplied with electricity capacity. Making matters worse, the slump in the price of renewables means that even existing coal plants struggle to compete on cost, let alone newly built ones. The average power tariff for state-owned NTPC Ltd. in the June quarter was 3.63 rupees per kilowatt-hour, or around $51 per megawatt-hour. New wind can currently be built for around $43/MWh in India and solar comes in at $37/MWh, according to BloombergNEF.

On top of that, generators are struggling to be paid because of the finances of the electricity distribution companies owned by India’s states, while shortages of water and coal itself mean plants often have to switch off even at times when they can make money. State-owned mining giant Coal India Ltd. may miss full-year production targets if output doesn’t pick up from rates seen in the June quarter, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Michelle Leung wrote Friday.

The bullish argument for Indian coal over the next decade is that the government bails out the distribution companies who will in turn bail out the generators; and that the grid simply won’t be able to integrate the 175GW of wind and solar that the government is targeting to be built by 2022, let alone the 500GW envisioned by 2030. As a result, state support will continue to prop up expensive, polluting soot as the only technology capable of keeping up with growing electricity demand.

An alternative scenario is that India meets most of its renewables expansion targets and lifts the efficiency of wind and solar plants closer to those seen elsewhere in the world. In that future, coal-fired electricity may already be within a few percentage points of its peak. With renewable power growing, fossil-fired plants would gradually be reduced to back-up generation to supply electricity after the sun has set, rather than providing the bulk of power through the day.

In truth, there’s not enough investment in either form of generation at the moment to make a sure-fire bet. Still, as we’ve argued, the collapse of financing for fossil fuels should give pause to anyone making bullish predictions for the future of carbon-intensive electricity, including the governments that are increasingly its main backers. Coal-fired power has long failed in terms of human health and climate impacts, but its raw economics are now collapsing, too. Even the might of the state can’t keep flogging this dead horse much longer.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments