A $700 billion fund is under pressure over plans to curb coal

South Korea’s National Pension Service, the world’s third-largest retirement fund, faces criticism over potentially weaker-than-expected plans to curb investments in coal.

The fund, which manages assets worth about $700 billion, is reviewing options including a proposal that would limit holdings of companies that generate more than half their revenue from coal mining and power generation. That’s a far more lenient threshold than global peers and one that would have only minimal impact on its portfolio.

“The negative consequences of the NPS failing to make climate-conscious investments will be enormous,” said Kim Sung-ju, an opposition party lawmaker and a former chairman of NPS. “Given its clout, the fund’s reluctance to actively respond to climate change can severely undermine the world’s net-zero efforts.”

The fund is continuing to work on plans for its coal-based investments after pledging to divest from the dirtiest fossil fuel more than a year ago. A local unit of Deloitte LLP in April completed a study which recommended the NPS should consider policies which would prohibit investments in companies that win either more than 30%, or more than 50% of their revenue from coal, according to a report seen by Bloomberg News.

Under the more lenient option, the NPS would retain almost 3 trillion won ($2.9 billion) of assets linked to coal in 2030, compared with 3.8 trillion in 2023, according to the research. The study only covered coal, and didn’t examine other fuels such as oil and natural gas.

The NPS declined to comment.

The fund needs to strike a balance between responding to climate risks and achieving stable growth from long-term investments, and several details of its plans need to be ironed out, said an NPS official, who asked not to be identified to discuss internal processes. The fund is aiming to make a decision before the end of the year, and the process has been slowed because President Yoon Suk Yeol, who took office in May, hasn’t yet nominated a welfare minister, who will chair the fund’s management committee, the official said.

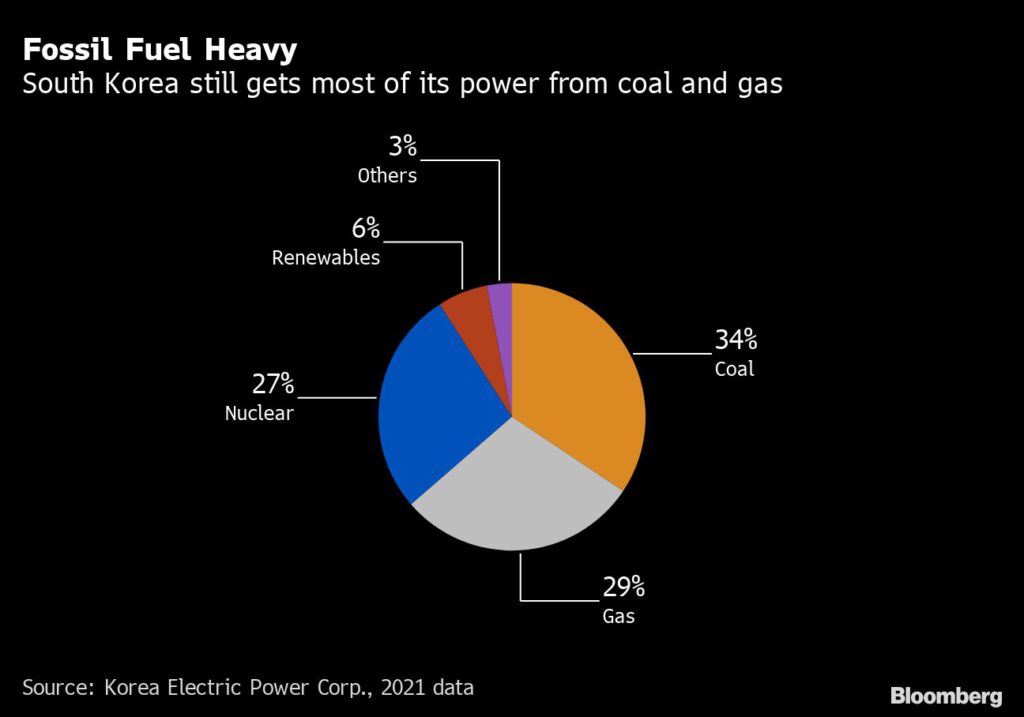

South Korea has set a deadline to zero out emissions by 2050 but President Yoon has been less eager than his predecessor to accelerate a transition away from existing energy sources. That may have reduced the pressure on the state-owned NPS to follow global pension managers in blacklisting fossil fuels, even as other investors, regulators and climate groups urge the fund to use its size and influence to help combat global warming.

The NPS is the largest institutional investor in South Korea’s 2,370 trillion won stock market and holds stakes in several companies with coal-linked investments including Korea Electric Power Corp. and Posco Holdings Inc.

Deloitte’s report suggested the fund could maintain investments in companies that are heavily reliant on coal, as long as they have energy transition plans in place and provide evidence of progress.

“There are just too many loopholes regardless of which option the NPS takes,” and the fund should consider all fossil fuel investments, not just coal, Lee Jong-O, a director at the Korea Sustainability Investing Forum, a non-profit advocacy and research organization, said by phone. “The NPS doesn’t seem to have the urgency to meet the nation’s climate goals.”

(By Heesu Lee, with assistance from Youkyung Lee)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments