A $60 billion mine propels Bougainville’s independence vote

Born out of bloodshed, colonial politics, civil war and the pursuit of mining riches, the independence referendum on the island of Bougainville starting on Saturday has been a long time coming for Barbara Tanne.

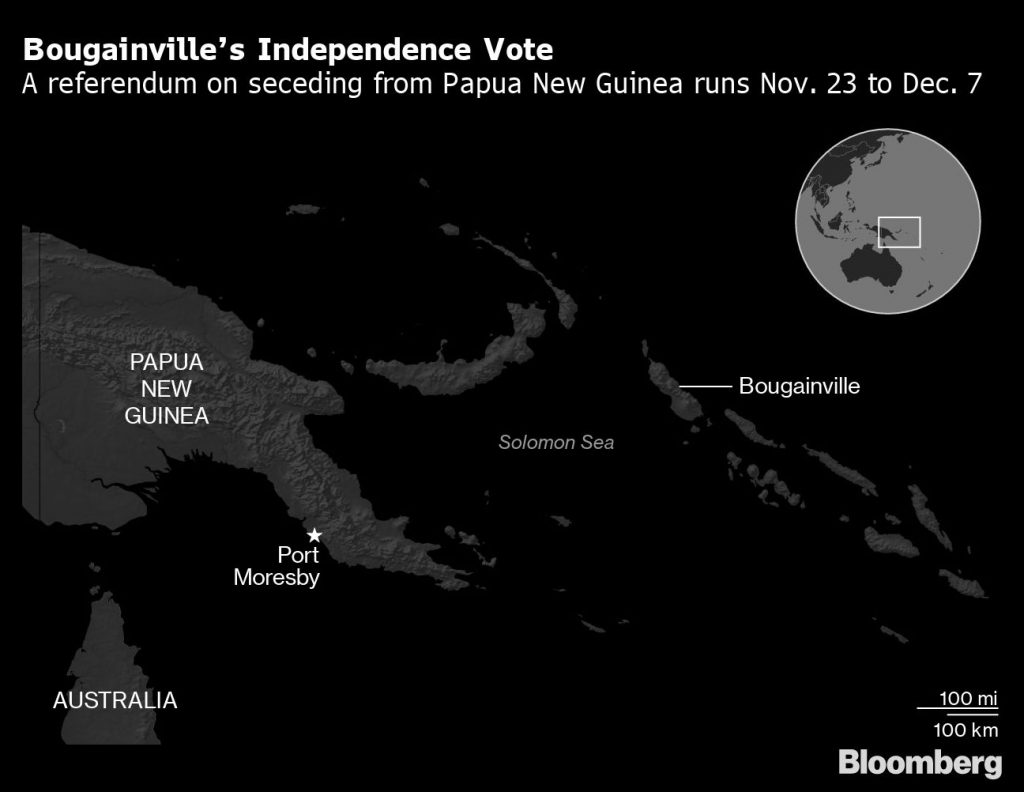

Tanne, one of the 300,000 or so people who live on the small group of islands in the South Pacific, has spent the past months criss-crossing remote villages to tell people about the vote, which could result in separation from Papua New Guinea.

“Everybody is saying ‘now is the time’,” said Tanne, 56, from her home town of Buka. “People are positive and they want to see the result, but I’m telling them that we have to be patient, because the next step could take a long while.”

As many as three quarters of voters may choose independence, according to one estimate, but even that wouldn’t guarantee the advent of a new nation. Any split would need to be approved by an act of parliament in Papua New Guinea, and the government in Port Moresby has indicated it wants Bougainville to remain a province.

With fewer people than Pittsburgh, an estimated per-capita GDP of about $1,100 and an economy reliant on money from the central government, Bougainville seems an unlikely candidate for independence. But it has one resource that could change its fortune, potentially giving it real and not just nominal autonomy — a massive copper deposit.

It is the country’s blessing and curse. The Panguna mine was the focal point of a 10-year civil war and has been shut since 1989, shortly after the conflict started, tainted by its bloody past and fettered by a tangle of environmental and ownership issues. But it remains central to what will happen to the islands after the vote is counted in mid-December.

Chinese developers

PNG Prime Minister James Marape told local newspaper the Post Courier in September that negotiators may be able to give Bougainvilleans greater economic independence while maintaining the country’s unity, hinting that such an option would be linked to Panguna, as “we owe it to them to help rebuild that place.”

While the mining industry will be hoping the vote unlocks Bougainville’s mineral resources, political powers such as China and the US will be watching the outcome for a potential new ally

While the mining industry will be hoping the vote unlocks Bougainville’s mineral resources, political powers such as China and the U.S. will be watching the outcome for a potential new ally.

At the junction of the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and halfway between Brisbane and the U.S. military base on Guam, Bougainville has a strategic interest as well as being a potential source of contracts for mining and construction companies.

According to a Sydney Morning Herald article on Nov. 17, one of the potential candidates for president of an independent nation, former Bougainville Revolutionary Army General Sam Kauona, has already been in talks with Chinese developers about helping build a port, bridges, roads and an airport. Without citing sources, the report said a delay by Papua New Guinea to ratify the vote could lead to a unilateral declaration of independence that may be recognized by China.

New direction

Whatever the result, Bougainville is certain to change. The 14-day vote offers two choices: stay in Papua New Guinea but with greater autonomy, or go for full independence.

“The status quo isn’t an option, so there’s no doubt this vote is the start of a new direction for Bougainville.” said Kerryn Baker, a researcher in Pacific Islands politics for the Australian National University. What’s unclear, he says, is the direction the islands will take. “If there’s independence, what’s the road map to get there?”

Annmaree O’Keeffe, who led Australia’s aid program in Papua New Guinea during the latter years of Bougainville’s civil war, says Bougainville has neither the skills in human resources, nor the financial wealth to become independent soon.

“To become an independent nation is very expensive — creating a defense force, immigration services, negotiating trade agreements,” said O’Keeffe, a non-resident fellow at Sydney-based think tank the Lowy Institute. “This takes a lot of money, which it just doesn’t have at the moment.”

Not surprising then that all eyes are on the old Panguna mine, which has an estimated 5.3 million metric tons of copper and 19.3 million ounces of gold, according to former operator Bougainville Copper Ltd. That would make the reserves worth about $60 billion at today’s prices.

But as O’Keeffe points out, “accessing the wealth without leading to more conflict is a big challenge.”

High risk

Major western mining companies would be loathe to restart operations at Panguna, said Peter O’Connor, a Sydney-based analyst at Shaw and Partners Ltd. “The uncertainty surrounding politics in that area would mean that anybody who’s going in is going to have a very long-term view and a balance sheet” to match.

He said Chinese operators have a high risk appetite, low cost-to-capital and need the resources.

Besides the potential loss of mineral wealth, Papua New Guinea has other reasons to resist independence for Bougainville. A split could encourage more of the nation’s 22 provinces to push for autonomy, undermining the government’s efforts to unify a country that has more than 800 languages and was constructed from a colonial carve-up less than 50 years ago.

“The whole of Papua New Guinea is talking about autonomy,” Deputy High Commissioner to Australia Sakias Tameo told a conference in Canberra on Oct. 10. “We would prefer the be the one country that we are today.”

Lowy’s O’Keeffe says the likely outcome of a vote in favor of independence would be a flurry of initial activity followed by a long list of criteria that would need to be to met before Papua New Guinea’s parliament would even consider a split.

“That’s what Marape will be seeking,” she said. “What prime minister ever wants to see part of their country split off under their watch?”

That won’t dissuade Tanne and other independence supporters from celebrating if the vote goes their way. But, as Baker at the Australian National University cautions, those trying to see further into the future would do well to heed Papua New Guinea’s tourism slogan: “The Land of the Unexpected.”

(By Jason Scott, with assistance from Aaron Clark)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments