The world’s biggest diamond mine is closing

The world’s biggest diamond mine—famed more for the fistful of coveted pink and red gems it yields each year than being a major producer of lower-quality stones—is being shuttered by Rio Tinto Group after almost four decades. Rivals from Russia to Canada hope that can help turn around the beleaguered industry.

Rio’s Argyle mine in remote Western Australia has transformed the sector since 1983 when the operation began supplying gems for both ends of the market. RBC Capital Markets and Panmure Gordon are among brokers, banks and competitors forecasting the closure could kick-start prices that have waned since 2011, according to PolishedPrices.com, an industry data provider.

Production at Argyle, about 2,600 kilometers (1,600 miles) northeast of the state capital Perth, is scheduled to end before the end of next year after finally exhausting its supply of economically viable stones, said Arnaud Soirat, Rio’s head of copper and diamonds.

“There is going to be a fair bit of supply which is going to come out of the market,” Soirat said in an interview Friday at the mine site. “In late 2020 we’ll be stopping operations and will start the rehabilitation of the site.”

Argyle is best known as the source of about 90% of the world’s prized pink diamonds—rose-to-magenta hued stones that command among the sector’s highest prices. Sotheby’s auctioned the 59.6 carat “Pink Star”, mined by Rio’s rival De Beers, for $71 million in April 2017, a record auction price for any gem. While they attract most attention, the pink stones account for less than 0.01% of Argyle’s total output.

The mine also is the biggest diamond producer by volume and that’s what has put the operation at the center of global oversupply. More than three-quarters of Argyle’s output is composed of lower-value brown diamonds, and the mine’s overall output sells for an average of between $15-$25 a carat, Canaccord Genuity Group Inc. estimated in 2017. That’s far less than the $171 a carat average price realized last year by De Beers.

A glut of cheap and small diamonds has eroded profits for nearly every miner and made it increasingly hard for the industry’s cutters, polishers and traders to make a profit. In December, some of Rio’s customers refused to buy cheaper stones, while De Beers has been forced to cut some prices and offer concessions to buyers.

Yet, with consumer appetite for diamonds stable, and major mines including Argyle scheduled to shutter, “the rational offset between supply and demand should lead to price growth,” Stornoway Diamond Corp. Chief Executive Officer Pat Godin said in March. Declining output, led by Argyle’s closure, will help revive prices, Toronto-based producer Mountain Province Diamonds Inc. said in May.

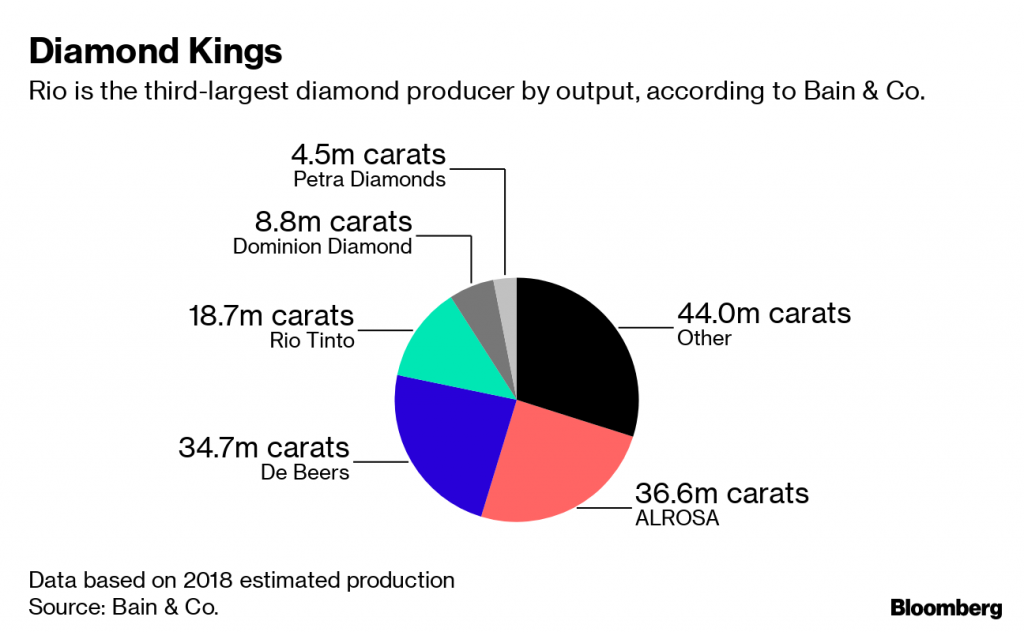

About 21 million carats a year of global diamond production—including about 14 million a year from Argyle—are scheduled to exit the market by 2023, a volume that’ll only partially be offset by the addition of new mines, according to Russia’s Alrosa PJSC, the world’s diamond biggest producer. The shortfall between annual demand and supply could be between 11 million and 35 million carats by 2023, the company said in a presentation last month.

“In terms of the pink diamonds, the impact is going to be even more dramatic” from Argyle’s closure, Rio’s Soirat said in the interview. “You can imagine the laws of supply and demand will apply, and you can imagine the impact that will have on those very rare pink, red, blue and purple diamonds.”

The producer estimates Argyle has only about 150 colored diamonds of sufficient quality left to extract and make available for its annual tender, a sale to invited buyers that showcases 50-to-60 of the year’s most valuable gems, he said.

The closure of Argyle will remove about 75% of Rio’s diamonds output, yet the impact on the producer’s earnings will be negligible

Prices of pink diamonds have already as much as quadrupled over the past 10 years, and buyers are “now just waking up to the potential impact that Argyle’s closure will have” in lifting values further, said Frauke Bolten-Boshammer, proprietor of Kimberley Fine Diamonds, a retailer based in the town of Kununurra, about 200 kilometers north of the mine. She has traded the gems since the 1990s.

Overall, the diamond sector probably also needs a boost to downstream demand, according to Richard Hatch, a London-based analyst at Berenberg. Mine closures that tighten supply “will help, but is it the shot in the arm that the industry really needs? Probably not,” Hatch said.

Buyers have been hit by a shortage of finance and stagnant end markets, while a weaker rupee has made gems more expensive for Indian manufacturers, who cut or polish about 90% of the world’s stones.

The closure of Argyle will remove about 75% of Rio’s diamonds output, yet the impact on the producer’s earnings will be negligible. Diamonds bring in only about 2% of earnings, while iron ore—the company’s top commodity—accounts for almost 60%.

Rio in 2016 shuttered the Bunder development project in India and in 2015 exited the Murowa mine in Zimbabwe. The producer’s only other producing diamond asset, Diavik in Canada, is scheduled to close in 2025, though exploration work is continuing to potentially extend that site’s life, Soirat told reporters Friday at Argyle.

Still, the company aims to retain a presence in the sector. While it could consider acquisitions to add new output, Rio’s main focus is on exploration—an option that’ll take longer to deliver new output growth. Work is advancing on the Fort a la Corne project in Saskatchewan, a joint venture project that potentially could enter production within five to 10 years, Soirat said.

Diamonds is “not a big business in Rio, however it is a very profitable business,” he told reporters, adding that the company has advantages in the sector that it can look to continue to exploit, including technical expertise and branding. “It’s not a commodity, it is luxury goods, and so the market dynamics are completely different.”

(By David Stringer and Thomas Biesheuvel)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments