Then on Monday, the U.S. Treasury threw a potential lifeline by making clear it’s not pushing for the company’s collapse.

“The U.S. government is not targeting the hardworking people who depend on Rusal and its subsidiaries,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said.

The Treasury softened its position in three ways. Mnuchin said it was considering a request to lift the sanctions against the company, it extended the period during which companies could keep trading with Rusal by almost five months, and it clarified exactly what dealings were permissible during that time.

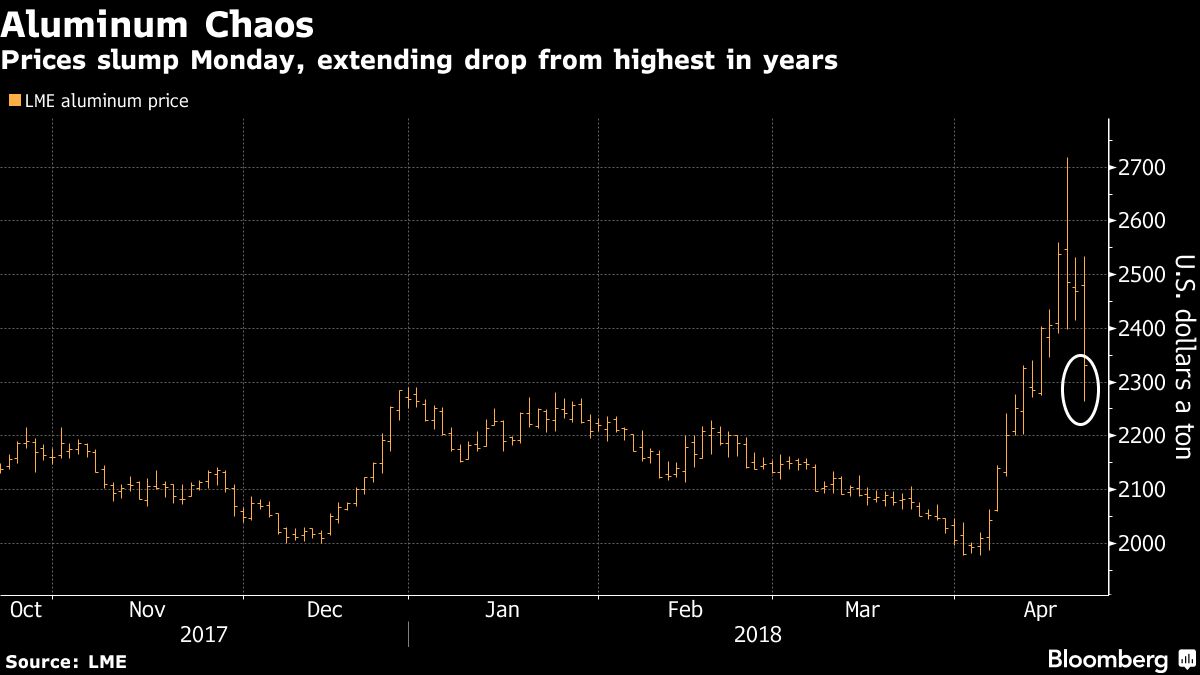

Aluminum posted the metal’s biggest one-day drop since 2010 in London and the slide continued on Tuesday. Rusal’s shares jumped a record 43 percent in Hong Kong.

The violent reaction showed how far the sanctions had roughed up the aluminum market. As the biggest supplier of the metal outside China, Rusal found itself shut out of international markets and the impact had started to cascade through the entire industry: traders stopped buying Rusal’s metal, shipowners refused to carry its products and miners couldn’t supply its plants with raw materials.

Now, some of those things may be possible — for a few months, at least.

“The market is clearly taking this as light at the end of the tunnel for Rusal,” said Oliver Nugent, a metals analyst at Dutch bank ING Groep NV.

The latest twist was expected but came sooner than expected, according to a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. report that said a restructuring of Rusal’s assets is the likeliest outcome. While the bank kept its three-month price estimate of $2,500 a metric ton, it acknowledged downside risks to the forecast.

It’s not clear whether the Treasury’s moves on Monday will automatically allow international companies to resume their deals with Rusal. Mining majors Rio Tinto Group and Glencore Plc have already declared force majeure on some contracts, while many traders, banks and shipping companies have frozen all dealings with the Russian company.

Still, some counterparties with long-term contracts may now be able to resume trading with Rusal under those contracts between now and Oct. 23, according to people familiar with the matter, asking not to be named discussing internal deliberations.

“Things have ground to a halt in terms of Rusal’s dealings with major western companies,” said Maximilian Hess, a senior political risk analyst at AKE International. “This extension going out until October will allow some of the supply contracts to be completed.”

Cautious counterparties

In particular, the Treasury’s clarification of its stance on international companies’ dealings with Rusal over the next six months resolved some key issues that had made counterparties wary of continuing dealings.

For example, in updated “Frequently Asked Questions,” the Treasury said that non-U.S. entities wouldn’t be subject to sanctions for transactions related to the winding-down of contracts with Rusal in the period to Oct. 23, and that payments related to such dealings wouldn’t have to be paid into a blocked account.

That may help buyers, suppliers and shipping companies that have existing contracts with Rusal continue to do business.

Trade flows

It’s important because the sanctions had all but frozen trade flows — most critically in the market for alumina, the raw material used to make finished aluminum. Rusal is a vital cog in a global interlocking supply chain that’s been thrown into chaos. For example, Rusal’s Aughinish alumina plant in Ireland buys bauxite that Rio mines in Guinea and sells to smelters across Europe.

“It’s the alumina market that’s really got to get through this perfect storm right now,” said ING’s Nugent. “If this gives any respite to the raw materials market, it does justify some of the weakness today” in aluminum prices, he said.

Nonetheless, while the Treasury’s moves on Monday may give some respite to Rusal, traders are likely to remain cautious. The license allowing companies to continue transactions applies only to existing contracts, not new ones, and it’s not clear whether companies that have already wound down dealings with Rusal are allowed to restart.

“If I were an employee of the Aughinish plant, I’d be looking at this as better news, but the storm is still there,” AKE’s Hess said.

In the longer term, the U.S. put the resolution of the sanctions in Moscow’s hands, saying it would drop the curbs on Rusal if billionaire owner Oleg Deripaska were to sell his stake and relinquish control. It’s not yet clear if that’s a solution the Russian government will be prepared to endorse.

“If it turns out that the sanctions do not stop plants from operating or workers from receiving salaries and sales volumes are maintained, then Deripaska suits the government as the owner,” said Andrei Margolin, an economist at the Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration in Moscow.

(Written by Jack Farchy and Yuliya Fedorinova)

Comments