The race to ditch Russian uranium starts in New Mexico’s desert

In a remote, dusty corner of New Mexico, so near to the Texas border that if you wander too close your smartphone changes time zones, sits a pristine factory that is the best chance for the US to wean itself off an addiction that few knew it had: uranium enriched in Russia.

Outside the $5 billion Urenco plant in Eunice, cacti and lizards bask in the fierce sunlight, watched by heavily armed guards. Inside, the facility is spotless, with bright, polished machinery that looks brand new even though some of the equipment has been in service for years. Hundreds of centrifuges, each at least 20 feet tall, spin at supersonic speeds and generate an ear-piercing whine that reverberates across a cavernous hall, where they separate the uranium isotopes needed to make fuel for nuclear power plants. For security reasons, parts of the piping that connect the Eunice machines are shielded from curious visitors.

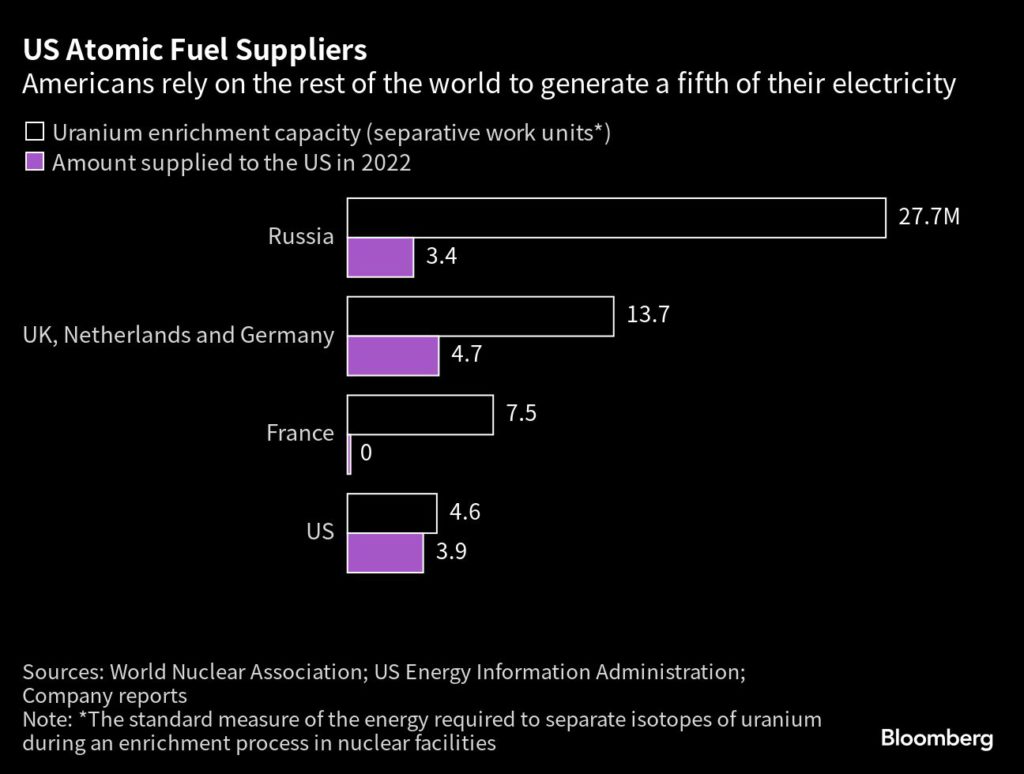

The plant supplies about one-third of US demand for enriched uranium and is in the process of boosting output by 15%. It’s the centerpiece of a transatlantic project to rejuvenate production of the fuel to feed the West’s fleet of nuclear reactors, a linchpin of energy security and efforts to reduce carbon emissions. Urenco Ltd. is the only commercial supplier of enriched uranium in North America. Currently, about half of the global supply comes from Russia, an uncomfortable reality for leaders in the US and Europe in the wake of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

The high levels of security are easily understood. The recipe to make nuclear fuel is one of mankind’s most-guarded secrets: its dual-use technology means the same methods for feeding reactors also apply to building bombs. For years, the US has refused to share or transfer fuel-manufacturing technologies — first developed for the Manhattan Project in the 1940s that made the bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But now, Washington is urging more countries to develop that capacity.

The trigger for that change of mind was the attack on Ukraine. Some 18 months on, Rosatom Corp. — the Kremlin-controlled nuclear group — is still the world’s biggest uranium enricher. It still supplies almost a quarter of America’s 92 nuclear reactors and dozens of other plants across Europe and Asia.

Western governments have avoided sanctioning Rosatom because doing so risks damaging their own nuclear industries and economies more than Vladimir Putin’s.

“We’re bearing the costs of an overreliance on Russia for nuclear fuel,” said Pranay Vaddi, a White House nuclear adviser at the National Security Council. “And it’s not just us, it’s the entire world.”

‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Reconstituting a North American fuel cycle and boosting the capacity of European providers is a massive undertaking. The recent coup in Niger, which has about 5% of the world’s uranium and has long been a significant supplier for former colonial ruler France, underscores the geopolitical stakes inherent in the business. South Africa’s national utility, Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd., allowed a nuclear trade agreement with the US to expire in December and then signed a deal with Russia to jointly produce nuclear fuel, part of an initiative to rebuild the African country’s own fuel cycle.

If Western nations fail in their bid to rebuild the sector, they will face a series of unpalatable options. They could continue to rely on Rosatom, presuming Moscow is still willing to do business. But given that most utilities only keep about 18 months of fuel inventory, if Russia were to stop selling, existing reactors may have to start powering down in the absence of alternative supplies.

Urenco, which is based outside London, reveals few details about how its centrifuges work, their dimensions or even how much nuclear fuel each one produces. The planned expansion of its New Mexico facilities to boost capacity will be completed in 2027 and, when combined with the parent company’s ramp-up in Europe, would be enough to cover Rosatom’s share of the American market, said Karen Fili, chief executive officer of Urenco’s US subsidiary, without disclosing the cost of the Eunice expansion.

“We are the very reasonable solution for the US,” Fili said. “The increased production from Urenco would be enough to cover any gap in Russian imports.”

While welcome, those reassurances underscore the economic vulnerability behind the efforts to reboot the West’s uranium-fuel business. US President Joe Biden and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged during a March meeting to diversify the nuclear fuel supply chain with “like-minded allies” and to better coordinate conversion, enrichment and fabrication. Within three weeks, they recruited France and the UK to help push Russia out of the nuclear fuel business altogether.

Although Europe gets about 30% of its enriched uranium from Russia, it has a larger installed production capacity than the US, and should be better able to adjust quickly. Urenco, a consortium of the UK, Germany and the Netherlands, is weighing expansion at sites in those countries, while France’s Orano SA plans to enlarge its domestic facility.

By the time uranium reaches a factory like Urenco’s in Eunice, it has already been through several stages of processing.

The first step is to identify rare uranium deposits in far-flung regions. Once it is mined and milled, the ore is converted into a fluorine gas and injected into casks. Those are shipped to enrichment facilities, where the uranium-hexafluoride — or UF6 — is fed into cascades of centrifuges making more than a thousand rotations per second. The uranium-235 isotope that’s needed to sustain a fission chain reaction makes up less than 0.7% of the raw ore. The enrichment process boosts the concentration to about 5%.

The process of converting milled uranium into UF6 gas is the most acute bottleneck in the US nuclear fuel cycle. The only conversion facility in the US was shuttered in 2017, when the global market was oversupplied and prices plunged. That forced utilities to draw down inventory and purchase internationally, opening the door to Russia and China, which together control about two-thirds of the global uranium conversion market.

Prices for UF6 have since rebounded tenfold, so Colorado-based ConverDyn is reopening its mothballed conversion facility in Illinois this year. But the company — a joint venture between Honeywell International Inc. and General Atomics — wants assurances from potential customers before it considers expanding enough to displace Russian supplies.

“Everybody is asking: What would it take? How much would it cost?” said Malcolm Critchley, ConverDyn’s CEO. “If people genuinely want to move away from Russia and genuinely want an alternative, they must underpin those commitments with long-term contracts.”

Around 10 customers signing decade-long contracts would justify a full expansion, Critchley added.

Even this approach looks piecemeal. Rosatom has integrated all parts of the nuclear-fuel cycle from tip to tail inside Russia. So far, about $20 billion of investments — including Eunice — and new commitments have been made by Western governments and companies toward replicating Rosatom’s reach, but it still looks like a complex jigsaw involving mining and conversion in Canada, with the sole US enrichment facility owned by a European consortium.

The Kremlin has derided the effort. “The agreement looks like an attempt at creating Frankenstein’s monster,” Rosatom said in its June newsletter. “History shows that only individual parts of this ‘supply chain monster’ have been functional so far.”

Even with a full-court press, it still may take the West five years to wean itself off Rosatom, said Dan Poneman, a former deputy US secretary of energy who’s now chief executive officer of Centrus Energy Corp. The Maryland-based company is developing a $150 million plant to produce a new type of uranium fuel for the next generation of nuclear reactors.

“There’s not enough non-Russian enrichment to fuel the world’s reactors,” he said, even with Urenco’s 15% boost in Eunice. “It’s not even close.”

The road from Los Alamos

The cycle for turning uranium into nuclear fuel was developed in the 1940s so J. Robert Oppenheimer could test atom bombs in the New Mexico desert in a race against Nazi scientists trying to develop the same destructive power. Almost eight decades on, the industry is in a different kind of competition.

Urenco is the second-largest enricher with a global market share of about 30% and half of the US market. It entered the sector in the mid-1970s, when the uranium-enrichment industry was dominated by US and Russian engineers whose purpose was to refine and stockpile huge volumes of the heavy metal for warheads. Urenco centrifuges in Europe are among the few outside Russia still spinning from the Cold War era.

“You switch them on,” said Boris Schucht, chief executive of global operations at Urenco Ltd., the ultimate owner of the Eunice plant, “and the only thing you don’t want to do is switch them off.”

The last US-owned commercial enrichment plant in Paducah, Kentucky, closed in 2013 after more than 60 years of operation. That loss of capacity — combined with the growing aversion to nuclear power that followed the 2011 meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant — fostered more reliance on Rosatom, even after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

But Russia isn’t just fueling yesterday’s projects, it’s also securing tomorrow’s customers by building nuclear power plants in China, India, Egypt, Turkey and Bangladesh that are locked into Rosatom fuel-supply contracts for decades. Due to the national-security dimensions and complexity, nuclear-fuel manufacturers tend to be government-controlled. That’s the case in China, Europe and Russia. Analysts estimate that Iran, a relatively new member of the uranium enrichment club, spent more than $13 billion on infrastructure costs alone to join.

Yet it’s not a particularly big business, at least when considering its strategic importance. Urenco made €427 million ($463 million) profit on €1.7 billion in sales last year. The real value of nuclear plants is that they stay in service for decades, lead to lengthy international relationships, and are viewed as important tools of diplomacy. That explains government involvement and why Rosatom packages long-term agreements to supply fuel with reactor construction deals.

The US wants to see investors profit from each link in the supply chain. Congress is considering legislation to establish a national stockpile of nuclear fuel made in the US — equivalent to the country’s strategic oil reserve that can be tapped in an emergency — with at least two contracts signed before 2027. On top of that, the US Inflation Reduction Act offers tax benefits and loan guarantees to the industry.

Urenco isn’t the only company set to benefit. Canada’s Cameco Corp., the biggest North American uranium miner and a key provider of other nuclear services, is acquiring a stake in Westinghouse Electric Co., which takes enriched uranium and makes fuel rods, in a deal that values the US-based company at about $8 billion. It’s expected to give North America a vertically integrated powerhouse — from digging the mineral out of the ground all the way to putting it inside a reactor — providing a blueprint for the development of an industry-wide supply chain.

Canada has the world’s third-biggest reserves of uranium and is the fourth-largest producer of ore which feeds reactors in the US and Europe among other places. “We’re getting invited to parties we never got invited to before,” said Brian Reilly, chief operating officer of Cameco. “We have tailwinds we haven’t seen in a long time.”

Before the coup in Niger, France’s state-controlled Orano proposed expanding the capacity of its domestic enrichment plant by about 30% by 2028, assuming it received enough commitments from international clients to justify spending €2 billion. That extra capacity could supply about 20 more reactors.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Orano signed enrichment contracts with some central European utilities, said Jacques Peythieu, the company’s senior executive vice president for customer and strategy. It’s also considering building a facility in the US.

“We have some clients that have clearly understood the strategic stakes, others that are still in a wait-and-see mode,” CEO Philippe Knoche said, “waiting for the outcome of the war.”

The International Energy Agency estimates that global nuclear capacity needs to double by 2050, from 2020 levels, to keep on track for helping reach net zero emissions targets. And the demand from individual countries is building. Sweden announced in August that it needs to triple nuclear power capacity over the next couple of decades to meet a surge in electricity demand and build at least 10 new conventional reactors by 2045 — all of which will need enriched uranium.

To hit the IEA target, reactors worldwide, including Russia, may need about 80% more uranium by 2040, or about 112,300 tons annually, according to the World Nuclear Association industry group.

In 2021, Urenco had no plans to expand in the US. But standing in a vast storeroom in Eunice crammed with ready-to-ship canisters, each filled with more than 2 tons of enriched uranium and worth $1 million, Keith Armstrong, the company’s chief of staff, said orders have increased almost 25% in the past year as the world tries to avoid Rosatom.

Armstrong, who has worked at Urenco for 11 years, said Moscow’s militarism had jolted the industry and exposed gaping vulnerabilities. “The invasion of Ukraine changed the market dramatically,” he said. “It went from a static state to ‘we need to expand now.’”

(By Jonathan Tirone, Will Wade and Francois De Beaupuy, with assistance from Samuel Dodge)

Related Story: Sweden to lift ban on uranium mining

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments