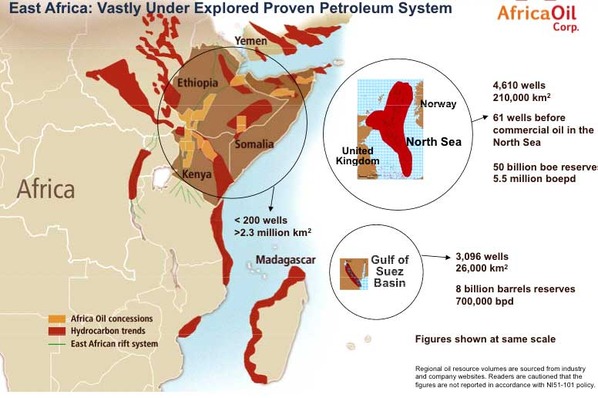

The huge risk-reward scenario in East Africa

Still, this vastly untapped region is the fast-rising favorite for Canadian juniors. The obvious question is: Why?

The potential prize is too big to ignore:

· ~5 billion in proven reserves in the Sudans and major discoveries elsewhere, with only a fraction of the potential explored

· Enough gas has been discovered in Mozambique to supply half of Western Europe for nearly a decade and a half—still, the country has barely been explored.

· Recent offshore discoveries of some 33 trillion cubic feet of gas put Tanzania on the map, and the risk here is relatively low. Tanzania has a natural gas processing plant on Songo Songo Island, with a 70 million cubic feet/day capacity. It is also planning an LNG terminal.

· Uganda discovered more than 2.5 billion barrels of oil in the last decade. This year alone, it discovered more than 1 billion barrels.

The risks fall into three categories:

1. A lack of infrastructure—pipelines, processing plants and refineries. You can make a big discovery, but how do you get it to market and monetize it?

2. Government greed.

3. Social/tribal tensions.

Sudan is a good example. Blessed with an abundant oil supplies, authorities recently announced that the country would double production in the next 2-3 years. However, it will miss its 2012 production target of 180,000 bpd due to social conflict.

Still, Canadian juniors like Calgary-based Emperor Oil (TSX-V: EM) and Statesman Resources Ltd (TSX-V:SRR) remain optimistic in Sudan.

Emperor Oil was a pioneer in Sudan, and recently signed an MOU to acquire 85% of a 50% interest in the 10,000 sq km concession Block 7 in Sudan. The other 50% is owned by the state’s National Oil Company, Sudapet.

“East Africa wants oil development,” says Emperor CEO Andrew McCarthy. “Infrastructure is an issue, though Sudan is in much better shape than most here.”

Infrastructure in this part of East Africa should improve in the coming years, with the big project being the $24.7 billion Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transit corridor (LAPSSET). LAPSSET includes a massive pipeline that would carry South Sudanese oil for refining in Ethiopia and Kenya and give the entire region another oil outlet.

Is it feasible? Yes, but capital is always difficult for this area, and McCarthy points out that the capacity of the Sudan-South Sudan pipeline could go to 1 million bopd at a fraction of the costs. The good news—competition creates lower costs for everyone.

McCarthy added that the new wealth being created by energy companies is a strong incentive for the different ethnic groups in East Africa to work together. He points to Sudan and South Sudan breaking apart peacefully, and any skirmishes after the fact have been stopped quickly once the oil—and hence the money—stopped flowing.

“Rather than fight over existing production they have chosen to expand their resource development so that there is a larger pie to share.”

Infrastructure is also the issue farther south in East Africa. Major energy producers are eyeing 130 trillion cubic feet of gas in the Rovuma basin offshore Mozambique, discovered by Andarko (US) and Eni (Italy). The government estimates there may be another 150 trillion cubic feet left to discover. Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron are eyeing this as well.

But for now, there is no way to bring extracted gas onshore, no facilities to liquefy it and no infrastructure for export.

We’re talking about $20 billion in investment to build the necessary infrastructure.

And ironically, the phenomenal success of the some of the pioneering juniors causes another problem: the governments start changing terms.

Several years ago East African countries were luring foreign oil companies onto their territory with desperately attractive deals. This trend is changing. Recent reserve discoveries have empowered these nations to ask for more.

There is pressure on juniors to foot the bill for ambitious infrastructure projects. East African states want the juniors to speed up their plans—drill more wells; build pipelines—get the money flowing! It can put the juniors with limited resources in a difficult spot.

But again, The Prize is big enough that several juniors have been able to attract major oil companies into their play.

For its next licensing round in oil and gas, Kenya is planning to switch to bidding for exploration blocks, rather than its usual one-on-one negotiations. While more transparent, which is good for business, this also reflects the new impatience. Kenya is also planning to rewrite its energy policy to reflect its greater negotiating power as a result of recent discoveries.

In Uganda, potential is vast and exploration just getting underway, but regulatory challenges are mounting.

Uganda wanted its oil and gas investors to pitch in for a massive refinery in the western area of Hoima. For investors, it was an unnecessary project with unnecessary expenses. Foreign oil companies would rather see Uganda’s oil refined elsewhere, more cheaply.

With new exploration technology (FTG, 3D seismic) being used on relatively virgin reservoirs, there’s a lot of potential for big new discoveries. But there are definitely challenges for energy producers looking to move into this are.

However, the Size of The Prize trumps all—the huge capital gains enjoyed by shareholders of Africa Oil, and before them Heritage Oil (HOC-TSX), attest to that.

Investors should be watching this area to see who’s next.

– Keith Schaefer – Oil and Gas Investments Bulletin

P.S. I’m almost ready to release the research on my newest play — and if you’re at all interested in capital gains plus dividends, you’ll find what I’ve uncovered extremely intriguing. In fact you may not believe the new dividend payout until you see it for yourself. I’ll show you what I mean as soon as I’m finished my research, this week.

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments