Strange days for coal with Glencore’s cap, China curbs

It’s been weird in the coal world in recent days, with the world’s largest shipper saying it’s capping output, biggest seaborne buyer China putting restrictions on some imports, and an Australian court saying mines must factor in climate change.

Throw in an executive at a major Indian coal-fired power generator saying his company won’t build any new plants as coal can’t compete with renewables, and it’s little surprise that environmental activists may be tempted to pop champagne corks.

It is accepted that coal consumption is likely to drop in the coming decades, to virtually nothing in Europe and North America, and will even start to decline in Asia.

The common theme at work is that coal is finding it harder to secure a long-term future in the world’s energy mix. But it’s worth unpacking the various developments and assessing the likely real impacts beyond public relations spin.

The most significant development this week was Glencore’s announcement on Feb. 20 that it will cap its annual output around its current capacity of 145 million tonnes.

Glencore is the world’s fourth-biggest coal mining company but also the largest supplier to the seaborne market, as miners that produce more – Coal India, China Shenhua Energy and Peabody Energy of the United States – are focused on their domestic markets.

Glencore said it was taking the step to help mitigate climate change, prompting commentators and activists to claim another victory in the campaign to end burning of the polluting fuel.

A profitable death

While Glencore may genuinely be trying to do its part to halt global warming, it’s also likely the mining giant has calculated that restricting coal output will be good for business.

It is accepted that coal consumption is likely to drop in the coming decades, to virtually nothing in Europe and North America, and will even start to decline in Asia.

But Glencore has probably calculated that this will be a slow, profitable death, and is positioning itself to take advantage.

While overall coal consumption is important for climate considerations, Glencore’s interest lies in the seaborne market, and it’s here that business may actually be good for an extended period, even as overall coal demand drops.

The seaborne market is set to become tighter, especially in Asia, as more countries in the region build coal-fired generators that rely on imported fuel.

Countries on this list include Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines and others in Southeast and South Asia.

The world’s three biggest exporters of coal, however, all have various reasons as to why they may not be able to supply much more than they ship now.

Indonesia, the world’s biggest shipper of thermal coal used in power plants, has a domestic reservation policy that forecasts declining exports as more fuel is diverted to feed local generators.

Australia, the biggest exporter of coking coal used to make steel and number two in thermal coal, may find it hard to boost its shipments, given increasing domestic opposition to the industry and the difficulties in getting new mines approved, financed and insured.

South Africa, the third-biggest exporter, has capacity constraints in its rail system and is also trying to balance the needs of its home market against the desirability of earning foreign exchange through exports.

Glencore, which spent some $3.7 billion last year on coal mines in Australia, has also probably acquired all the assets it needs in the coal sector.

Its mission now is to operate these mines efficiently and to try and ensure that prices remain as high as possible.

It may be cynical, but one way to do that is to say the company will cap output, thereby helping to keep the seaborne market tight and prices elevated.

China’s spanner

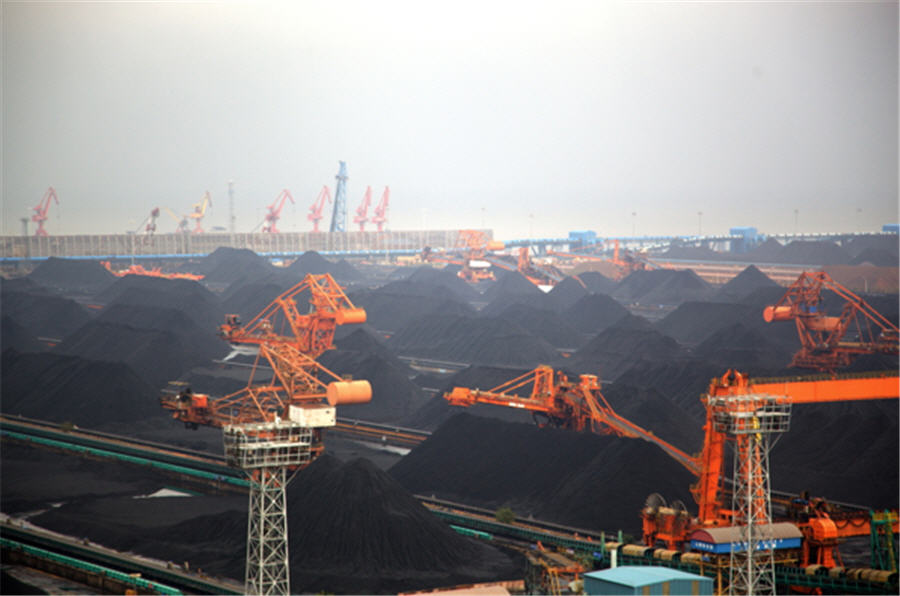

China is showing that two can play that game, with customs at the northern port of Dalian placing an indefinite ban on imports from Australia, and restricting those from other countries, according to an exclusive Reuters report on Thursday.

This isn’t the first time China has taken such measures, and the most likely outcome is that imports will decline for a period of time, but may eventually recover.

Much of the coal China imports from Australia is coking coal, and this is harder to source from other countries, with the only real alternatives being Canada and the United States.

What is clearer is that China, the world’s biggest coal importer, wants to limit its total imports, which means that over time it’s unlikely to be much of a growth market.

India, the second-biggest coal importer, looms as a great hope for the sector, but the Coaltrans India conference this week in New Delhi showed that while imports may grow this year and next, a dearth of new projects and the likely eventual improvement of domestic coal availability should result in a shrinking market.

New-build coal plants are struggling to compete against wind and solar in India, with Rajit Desai, an executive at major private generator Tata Power, telling the conference that his company wasn’t looking at developing any new plants, and will instead focus on buying existing units that are effectively distressed assets.

In another apparent victory for climate activists, an Australian court ruled on Feb. 8 that a mine development couldn’t go ahead, citing the impact from the greenhouse emissions that would be created.

While the mine in question most likely would have been rejected on other grounds, such as its close proximity to a retirement complex, the court nonetheless signalled that climate mitigation may become a part of any future approval process.

Putting the recent developments together gives a picture of a fuel battered from all sides.

But there is always a caveat. In this case, it’s simply that vast numbers of coal-fired power plants in Asia are still in the early stages of useful lives, and will likely operate for decades to come.

Coal may be down, but it’s far from out. I’m sure Glencore’s canny chief executive, Ivan Glasenberg, would agree.

(By Clyde Russell; Editing by Tom Hogue)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments