Russia’s $40 billion gold buying binge is slowing down

Russia, the world’s biggest buyer of gold, is losing interest in the precious metal.

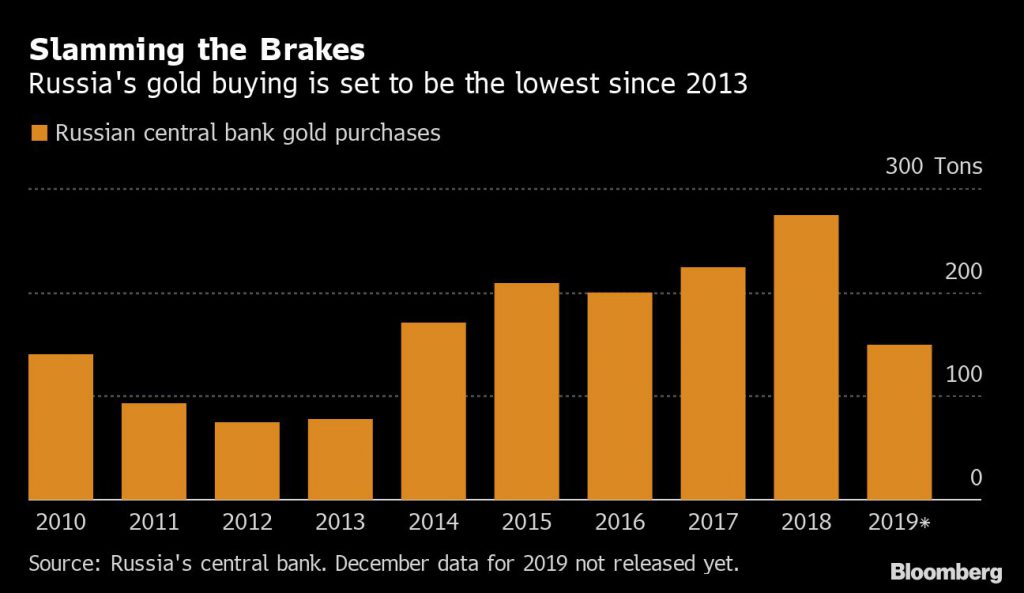

After spending an estimated $40 billion on gold in the past five years, the central bank is starting to rein in spending. It bought 149 tons of gold in the first 11 months of 2019, 44% less than the year before. Annual purchases are expected to be the lowest in six years.

Analysts say that Russia’s central bank has maxed out the proportion of gold it wants to keep in reserve. They also view the threat of U.S. sanctions and the need for a buffer against economic shocks diminishing as issues like the annexation of Crimea, election interference and the poisoning of a former Russian spy on British soil fade from public conversation.

Bullion exports were 100.5 tonnes last year, compared with 16 tonnes in 2018

To be sure, even at these lower levels, Russia is still buying a lot of gold and ranks at the top of the biggest purchasers. The country owns 2,262 tons of the precious metal, worth $106 billion, and stores some in vaults at the central bank in Moscow.

Russia’s relentless gold buying in recent years has been a key pillar of support, putting a floor under the market as investors ditched havens and bought riskier, higher-yielding assets.

Now, as bullion scales a six-year high, the key question is whether Russia’s decision to tap the brakes will hurt gold demand and prices, or buyers will come in from elsewhere. Gold has climbed 20% in the past year to $1,557 an ounce.

“If gold is protection against the toughest sanctions, then it’s logical to assume that there’s no need to buy gold in such volumes anymore,” said Denis Poryvay, an analyst at PJSC Raiffeisenbank in Moscow.

Putin warned shortly after his inauguration for a fourth term as president in 2018 that Russia was seeking to “break” from the dollar and diversify to bolster “economic sovereignty.” The country increased gold holding fivefold since 2007 and bullion now makes up about 20% of total reserves, the highest share since 2000.

The proportion of gold relative to other assets held by Russia’s central bank should stabilize, said Sofya Donets, an economist at Renaissance Capital in Moscow. She expects purchases to continue, but at a slower pace.

There’s plenty of investor appetite for gold financial products given geopolitical turmoil and economic growth fears, which should offset the drop in physical gold demand from Russia, said Ole Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo Bank A/S.

The slowdown does change business for Russia’s gold producers and banks, who are selling gold overseas instead of relying on the central bank to be the main buyer. Bullion exports were 100.5 tons last year, compared with 16 tons in 2018, according to custom data.

It’s possible that future exports might come directly from mining companies. Polyus PJSC, Russia’s biggest gold producer, has said it expects the government to give licenses to miners that would allow them to freely sell gold overseas. Currently, only banks have that permission.

(By Yuliya Fedorinova and Andrey Biryukov)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments