Rusal’s political comeback powered by “green” aluminium

Political rehabilitation doesn’t get much better.

Just over a year ago Russian aluminium producer Rusal was hit with swingeing sanctions by the U.S. government.

The company’s owner, Oleg Deripaska, was accused of a litany of misdeeds by the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), all of which he denied, and his sprawling industrial empire, including Rusal, was slapped with secondary sanctions.

Those sanctions were lifted in January after Deripaska agreed to reduce his control in Rusal.

Just three months later in April Rusal landed a major equity and supply deal with Braidy Industries, which is planning a state-of-the-art aluminium rolling mill in Kentucky.

The deal, which will see Rusal invest $200 million for a 40-percent stake in the plant, is an obvious win-win for both parties.

Braidy gets an investment booster towards its construction costs of $1.6 billion and Rusal gets political cover against any future punitive action by the U.S. government.

But the deal is also significant for what it says about the state of the U.S. and global aluminium markets.

Let the good times roll

Braidy’s Atlas mill is scheduled to come on stream in 2021. Extraordinarily, it will be the first greenfield aluminium rolling mill in the United States in 37 years.

The investment is predicated on the current strength of U.S. demand for sheet aluminium, particularly from the automotive sector, where aluminium continues to gain ground against steel due to its light-weighting qualities.

“It is going to be the best five years for rolling mills in decades”, Braidy chief executive and chairman Craig Bouchard predicted at research house CRU’s aluminium conference in London last year.

Braidy has ambitions not just to fill a widening supply gap in the U.S. market but also to break the mould in terms of new products for the automotive and aerospace sectors.

Its board includes two senior past and present alumni of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the company last year bought two companies, Veloxint and NanoAl, specialising in powder metallurgy and nanocrystalline strengthening technology respectively.

What Braidy hasn’t been able to secure, up until April, was a supplier of aluminium in the right quantity and with the right qualities it needed.

Deficit market

Craig Bouchard made another predication at last year’s CRU conference.

“Two large aluminium smelters will be built in the United States in the next five years,” he said, explaining, “you can’t have three working smelters in a market the size of the United States.”

On paper he may be right, but the reality is that no-one is planning on building a new U.S. aluminium smelter.

The United States remained a major net importer of primary aluminium to the tune of 4.1 million tonnes last year

Idled smelting capacity has been restarted thanks in part to U.S. tariffs on imports of the metal. There are now seven operating smelters in the country but the import dependency remains.

Alcoa’s resurrection of its Warrick smelter in Indiana, announced months before the tariffs came into effect in March last year, was driven by the needs of its own rolling mill on the same site, leaving nothing for the wider market.

Restarts by Century Aluminum and Magnitude 7 Metals may have helped narrow the U.S. supply-demand gap but they haven’t closed it.

The United States remained a major net importer of primary aluminium to the tune of 4.1 million tonnes last year.

Sanctions against Rusal relegated it from second largest to third largest supplier last year after Canada and the United Arab Emirates.

But with sanctions gone Rusal is confident of returning to its historic number two spot.

And as Braidy noted in its press release, “no U.S. producer of prime aluminum is able to supply the huge quantities required” for the 300,000-tonne per year (finished products) mill.

Particularly not the sort of aluminium Braidy wants.

“Green” aluminium

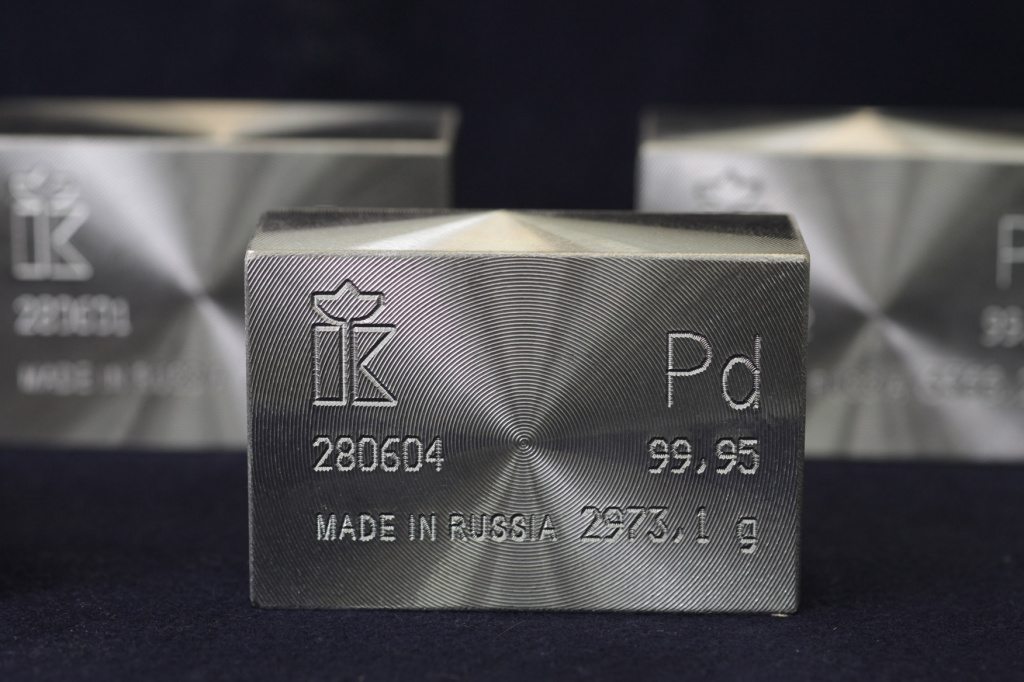

Rusal’s unique selling point for supplying 200,000 tonnes per year of metal over a 10-year period is its “ALLOW” aluminium brand.

The brand comes with independently-verified certificates of carbon footprint from specific hydro-powered smelters in Siberia.

In the case of the Braidy supply deal, the metal will come from the new Taishet smelter, work on which was briefly interrupted by the U.S. sanctions.

Rusal boasts its “ALLOW” brand has a “guaranteed low carbon dioxide footprint” of less than four tonnes of CO2 per tonne of metal.

The Russian company is not alone in pushing its low-carbon credentials. Other producers with hydro-electric power supplies such as Rio Tinto and Norway’s Hydro are doing the same.

Aluminium smelting is an energy-intensive business and the market is starting to differentiate between “green” low-carbon metal, powered by hydro, and “black” high-carbon metal powered by fossil fuels, particularly coal.

Braidy wants its new mill to be the greenest in the United States, targeting 20 percent lower carbon emissions than its nearest competitor.

To get there it needs low-carbon aluminium. “No U.S. domestic smelter currently delivers low-carbon primary aluminum slabs,” it said, making Rusal something of a no-brainer partner.

“Rusal is the sole primary aluminum producer globally that is capable of meeting Braidy’s quantity requirements and sustainability standards,” the company added.

Green drivers

The significance of this U.S.-Russian supply deal is the centrality of low-carbon aluminium.

It’s a sign that carbon-weighting is becoming a differentiator in terms of supply chain if not, yet, in price.

Braidy wants its new mill to be the greenest in the United States, targeting 20% lower carbon emissions than its nearest competitor

Automotive companies in particular are looking to boost their green credentials, a process that is accelerating with the shift towards electric vehicles.

Within days of the Rusal deal Braidy announced it would be cooperating with German auto-maker BMW on certifying its aluminium alloy sheet and creating a closed-loop recycling system.

A “groundbreaking collaboration” was how Lord Barker, chairman of Rusal’s ownership company EN+ and now co-chairman of the Braidy Atlas mill, described the BMW deal.

The tie-up “is just the beginning of opportunities as we competitively combine the highest quality aluminum with the lowest-carbon content yet, together setting an exciting new standard not just for North America but our industry globally.”

Sounds like the usual press release puff but in this particular case Barker’s comments may prove to be spot on.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Alexandra Hudson)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments