The rising cost of socially responsible investing: Mark Gilbert

Both companies and the fund managers that invest in them are under pressure to pay more attention to environmental, social and governance issues. For the former group, that requires delivering increased transparency on an ever-expanding range of metrics. For the investment crowd, tailoring strategies to address the new demands means increased spending on data – at a time when fees are slowly but steadily being eroded.

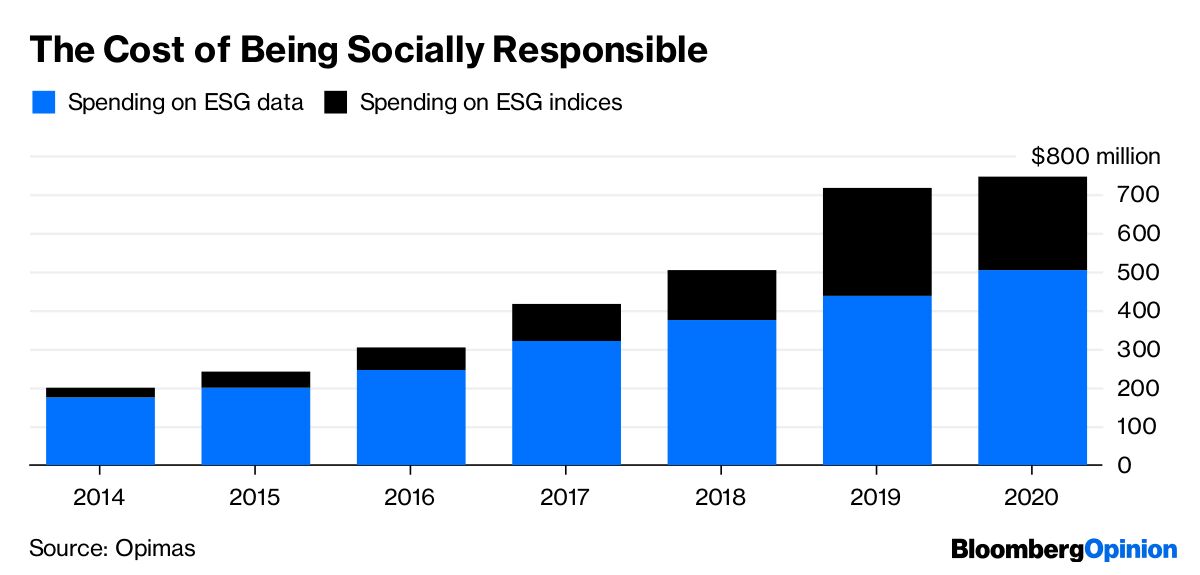

A study published this week by capital markets consultants Opimas predicts that the cost of buying ESG data will rise to about $750 million next year, an increase of almost 50 percent from last year and up by almost 300 percent since 2014.

It remains to be seen who will bear the burden of the increased costs associated with harvesting the observations needed to power ESG investing

The surge in spending reflects an explosion in investment products that are marketed as being more socially responsible in their objectives. The number of investment managers signing up to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment increased by 18 percent last year to 1,111. In July, the sovereign wealth funds of Kuwait, New Zealand, Norway, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates met in Paris and agreed an aligned strategy to press the companies they invest in to publish assessments of climate-change risk and carbon-reduction strategies.

The growth in investment products with ESG mandates is fueling a corresponding rise in indexes designed to track such strategies. There are more than 3.7 million indexes worldwide, according to a November study published by the Index Industry Association. ESG indexes were the fastest growing part of the market, with the number of them climbing by 60 percent in the year to mid-2018, the IIA said.

And it’s not just the world of equities that’s shifting. In fixed income, issuance of so-called Green Bonds that promise to spend their proceeds on environmentally friendly projects reached $136 billion last year.

Opimas reckons more than $30 trillion of assets globally are now assigned to ESG strategies. That total has grown by more than 30 percent in the past two years and is set to increase by a further 17 percent in the next two years. So the demand for data on how companies are conducting themselves is growing.

The data providers looking to fill that information gap include Sustainalytics, Truvalue Labs, Arabesque and EthiFinance. (Bloomberg LP also provides ESG ranking data and ESG indexes.)

Technology can help improve the breadth and depth of ESG intelligence. Data based on surveys filled out by company employees is disproportionately derived from bigger firms with more resources to do the paperwork. By automating the collection process, the firms harvesting the metrics can widen their nets and cut the cost of acquiring the metrics. And that’ll get easier as governments oblige companies to improve their reporting standards.

But as the investment strategies become more sophisticated, so will the demand for deeper and more standardized data. Funds that seek to qualify as ESG compliant by exclusion – by screening to bar pre-identified companies and industries such as those involved in mining or arms production – are pretty simple to design. Shifting to a more positive stance that puts more money into companies that score more highly based on ESG criteria like carbon output or gender diversity will require more refined numbers.

There’s also the issue of materiality. Environmental concerns are more pressing for a transport company than for a bank, for example. Carbon emissions matter more for a utility than a media company. And veganism’s growing popularity as a way to offset global warming affects food producers and restaurant chains more than the gaming industry or technology companies. So a one-size-fits-all approach to the evidence won’t work.

It remains to be seen who will bear the burden of the increased costs associated with harvesting the observations needed to power ESG investing. Fund managers may find customer enthusiasm for saving the planet diminishes in the face of higher fees and lower returns. But the growth of responsible investing is likely to continue unabated, even if the associated expenses are also headed in just one direction. As the saying goes, if you think knowledge is expensive, try ignorance.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of “Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable.”

(By Mark Gilbert)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments