Rio’s demolition of sacred site doesn’t match its image

It seemed like an incident from another era.

Rio Tinto Group last month demolished a 46,000-year-old site sacred to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples to make way for an expansion of its Brockman 4 mine in Australia’s iron-rich northwestern Pilbara region. The act has been likened to the destruction of Palmyra by the Islamic State.

It wasn’t only the Juukan Gorge caves that were blasted, though. Such a blithe act, and management’s subsequent inability to explain it, has undermined the decades Rio Tinto spent presenting itself as the socially responsible face of the mining industry.

Rio Tinto has spent decades burnishing a reputation for treating landowners better than some of its peers — but it’s a lot easier to be the good guy when the deck is so heavily stacked in your favor

How could such an event happen? If you see mining companies the way they like to present themselves — as benevolent middle men, aiding the economic development of formerly colonized peoples while providing materials for the industrial development of the planet — then it’s inexplicable that they could display such indifference at a site nearly three times as old as the Lascaux Caves.

That’s mostly a story for the cover of the corporate responsibility report.

While mining companies employ plenty of people sincerely committed to land rights and no doubt believe much of their own rhetoric, a middle man isn’t working for the sake of his suppliers or customers —he’s trying to maximize his own returns. When you’re dividing up the pie from selling mineral products, any cash spent giving landowners just compensation is money that’s not going to shareholders.

Rio Tinto has spent decades burnishing a reputation for treating landowners better than some of its peers — but it’s a lot easier to be the good guy when the deck is so heavily stacked in your favor.

As in many parts of the former British Empire, ownership of land in Australia was transferred to the Crown by a legal fiction upon European invasion in 1788. Until the middle of the 20th century, Aboriginal people in remote areas often worked as ranchers or servants in return for tobacco, sugar, tea and clothing — conditions not many rungs above slavery. The current disparate Indigenous Australian land-rights regimes were established from the 1970s to the 1990s against that backdrop. Despite the triumphs of figures such as Vincent Lingiari and Eddie Mabo in using strikes, political appeals and legal cases to win formal rights over land, campaigners have always had to fight off the back foot.

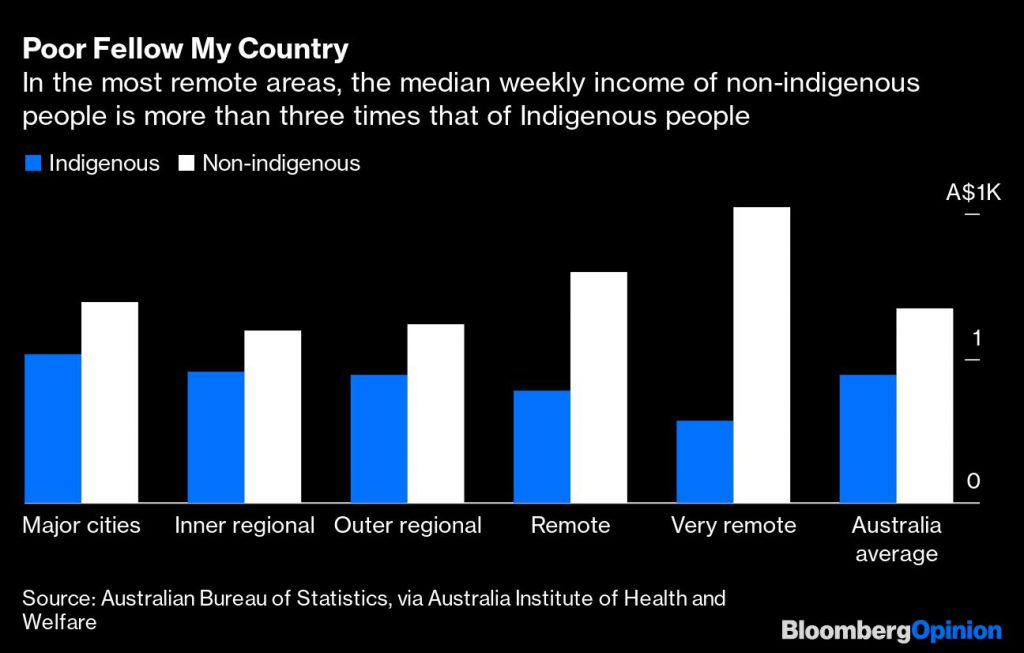

The result isn’t hard to see on a visit to an outback Aboriginal community. Despite the fact that such areas host some of the world’s most lucrative mines, Indigenous Australians die about 14 years younger than their non-indigenous neighbors in remote areas. In the most isolated regions, they’re paid just 28 cents for every dollar earned by others and four out of 10 households are overcrowded.

I’m from the U.K., where landowners still form an aristocracy that includes many of the country’s richest people. It’s depressing that as a migrant to Australia, I’m better off than most of the traditional owners on whom this country’s wealth was built.

This manifest injustice is explained in a variety of ways. Legally, land rights for Indigenous Australians are considered to have been “extinguished” if they were driven off their land in the past to make way for ranching, mining, real estate or infrastructure. That formula, one of the cornerstones of the country’s so-called native title system, bestows a blessing on a historical act of theft, rather than seeking to redress it.

Politically, the miserable conditions that prevail in many remote Aboriginal communities are blamed on social breakdown and the perception (often justified) that money spent on Indigenous advancement has been wasted on corruption and mismanagement — in essence, blaming Indigenous people for their own dispossession and exploitation.

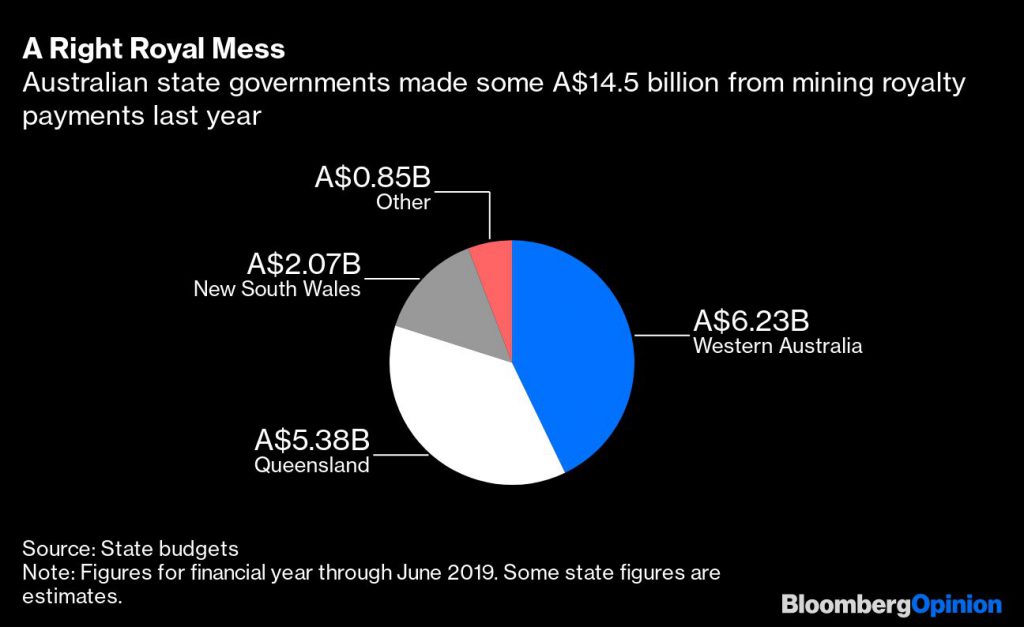

For all that such problems are attributed to a surfeit of “welfare,” though, Australia spends just A$3.3 billion ($2.26 billion) a year on Indigenous-specific government programs, with much of that budget dedicated to closing inequalities in education and health. That’s far less than the A$14 billion or so a year that state and territory governments get from mining royalty payments.

A first step toward reversing this would acknowledge the immense damage that mining and industry can do to landscapes that are an essential part of the world’s cultural legacy.

Aboriginal people were the first to colonize a new continent by sea, and were grinding seeds for flour and stone to make ax-heads 20,000 years before the same technologies helped kick-start the agricultural revolution in the Fertile Crescent. At Murujuga near the Pilbara iron ore port of Karratha, a nominated world heritage site hosts more than a million petroglyphs — including depictions of extinct megafauna and the oldest carved images of human faces — hard against an LNG terminal, explosives factory and fertilizer plant.

The destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves wasn’t an isolated incident. The Pilbara is thick with such cultural artifacts. A few days later, BHP Group received approval from Western Australia’s government to demolish 40 sites. Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. is seeking similar permission to expand its Solomon mine, where excavated sites include a cave whose occupation dates back 60,000 years.

The solution isn’t to stop mining. In communities that have suffered neglect by the state, these companies are often welcomed as the only partners in economic development — but the current regime is clearly not working for traditional owners. What resources companies have always sought is a “social license to operate.” For too long, though, those notional licenses have been handed out in return for relatively paltry royalty payments, often in the form of in-kind agreements to employ local workers and provide health, education and infrastructure that the state fails to fund properly.

What’s needed is legal and political change. Australia’s native title laws skew the playing field in favor of resources companies, and must be reformed to give local communities rights to a larger share of the billions of dollars their land produces. The deal that South Australia state recently handed out to mostly white farmers with little fanfare — a cash royalty on new gas production equivalent to about 1% of the sale price — is the sort of settlement that many Aboriginal groups have fought and failed to win through decades of court battles.

There are signs that change may be afoot. Australia’s High Court last month denied an appeal by Fortescue against a 2017 judgment, ensuring the Yindjibarndi people would hold a form of native title close to freehold land ownership. That precedent should strengthen the hand of Indigenous groups in negotiating with mining companies in the future.

A separate judgement last year also gave more guidance for how the value of native titles should be assessed, and found it to be substantially above the sort of sums that have typically gone to title-holders. If similar payments were assessed for even just 5% of native title land, traditional owners would be entitled to some A$280 billion, according to one analysis of the case by law firm MinterEllison.

In the Australian context, such enormous numbers are generally regarded as evidence that Indigenous land claims are politically impractical. In fact, they’re a small demonstration of the scale of what has been stolen. It’s well past time for those rights to be restored.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments