Palladium prices still aren’t high enough: David Fickling

Platinum’s lesser-known cousin keeps going from strength to strength.

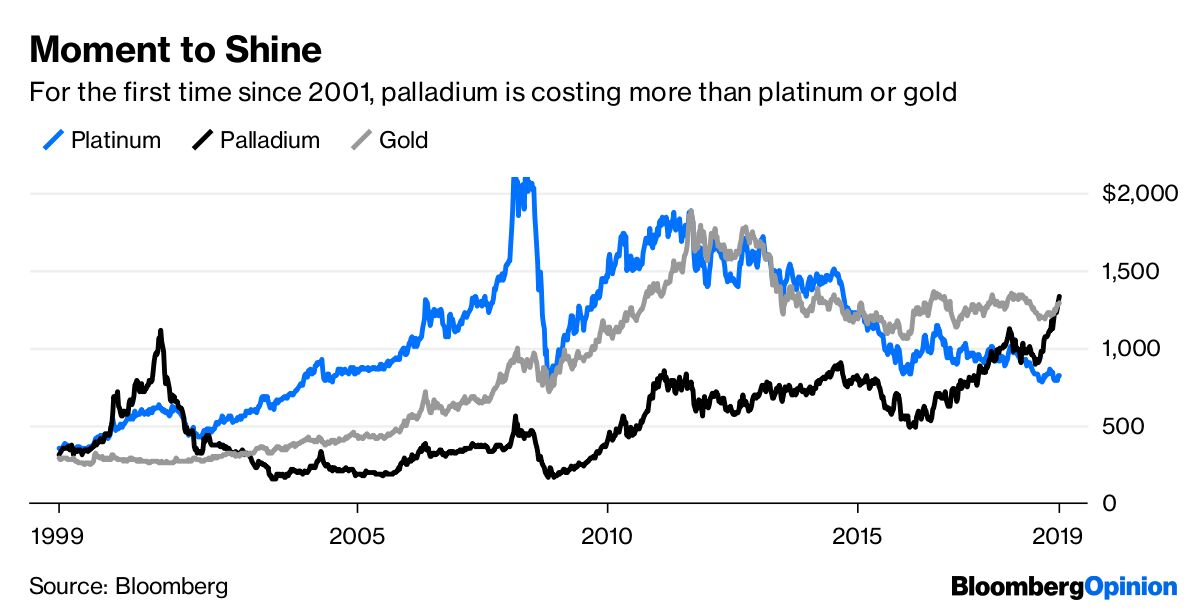

Palladium, once considered an unattractive byproduct of platinum mining until the rise of catalytic converters in the 1970s, is hitting new records. Spot metal peaked at an all-time high $1,344.41 a troy ounce Wednesday. Over the past month, it’s been more costly than gold, which hasn’t happened since 2002. From a point a decade ago when an ounce of platinum bought you more than 5 ounces of palladium, it now buys you about 0.6 ounces.

You might think this spike will spark an immediate reversal and slump, as is often the case with commodity prices. That may not happen, though, because prices still aren’t high enough to prompt a supply surge.

Prices for byproduct palladium will have to get a whole lot higher to tempt them to dig up yet more of their money-losing main product, platinum.

Palladium and platinum are part of an intertwined group of rare metals that occur in only three regions on the planet: southern Africa, Siberia, and, in smaller amounts, the U.S. and Canada. These platinum group metals crop up in the same deposits, so it’s next to impossible to produce platinum without getting some palladium, and vice versa. As we’ve argued before, that means the fortunes of the two are intimately bound together.

That’s important, because the diesel scandals engulfing the global car industry in recent years are reducing industrial demand for platinum, which is used more in diesel catalytic converters. Conventional gasoline-engine cars use more palladium in their exhaust scrubbers — and while that sector isn’t looking too hot right now either, the metals are moving in opposite directions. Autocatalyst demand for platinum has been falling for three years, according to Johnson Matthey Plc, a refiner of the metals, even as the industry’s consumption of palladium rises.

For the southern African miners who dig up about 80 percent of the world’s platinum and nearly half its palladium, this is a problem. Even at current elevated palladium prices, they’re struggling. With platinum hovering around $800 an ounce for the past six months, only about a quarter of their deep, dangerous and perennially strike-threatened mines are seeing market prices above their all-in production costs, according to data from Minxcon Group, a consultancy:

That’s not a one-off situation. For most of the past decade the five miners who dominate the southern African industry — Anglo American Platinum Ltd., Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd., Lonmin Plc, Sibanye Gold Ltd., and Northam Platinum Ltd. — have failed to crack a double-digit return on equity, which ought to be the baseline for a worthwhile investment.

There’s one way out of this toxic relationship, and it’s buried under the Siberian permafrost. In contrast to the tarnished southern African platinum industry, MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC is a truly precious metal. While palladium makes up about a third of the platinum-group output from South African mines, in Norilsk’s pits on the frigid Taymyr Peninsula the ratio is closer to 80 percent.

As a result, investors prepared to put up with the prodigious political and shareholder risks around Norilsk are sitting on a very attractive stock: With shares valued like those of BHP Group and Rio Tinto Group at around 6 times blended forward 12-month cash flows, its return on equity is north of 50 percent, and hasn’t dropped below 10 percent in a decade.

The trouble with Norilsk is that it’s not rushing to produce much more. Its forecast range for platinum-group output will edge up by a spare five tons between 2018 and 2020, according to its latest production guidance. Further out, there are plans to increase ore output from its Talnakh pit by about 20 percent by 2025, and after that the development of an enormous unexploited resource through a joint venture with Russian Platinum Plc — but in the near term that’s not going to help much.

Even the weak conditions in the car industry, which consumes about four-fifths of the world’s palladium, may not be enough to offset this situation. The real driver of palladium catalyst demand in recent years has been not so much rising volumes of car sales, but tighter emissions regulations that require larger amounts of the metal in each car sold. Despite U.S. attempts to wind such rules back, that should make palladium still more attractive in the rest of the world.

At some point over the next decade — when electric cars start to seriously eat into gasoline’s market share, and those massive Russian projects come on stream — palladium’s time in the sun is going to end. Right now, though, it’s still gleaming.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments