Pakistan’s milewide open air mine shows why coal won’t go away

In the flat scrubland of Pakistan’s scorching Thar Desert, hundreds of workers have been toiling for two years in the vast open pit of the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Co. Taking three-hour breaks during the hottest part of the day and living in a makeshift village of shipping containers, they’re digging for fuel to sustain a $3.5 billion power project. So far they’ve scraped away about 500 feet of Aeolian sand, dirt, and coal to create a milewide hole.

Seven hundred miles to the north, in the Cholistan Desert, lie the skeletal beginnings of a solar farm that’s supposed to expand to eight times the size of New York’s Central Park. It’s the largest solar project in Pakistan, where the government has recently announced an ambitious plan to generate 60% of its power from renewable sources such as sun, wind, and water in about a decade.

In the Cholistan Desert lie the skeletal beginnings of a solar farm that’s supposed to expand to eight times the size of New York’s Central Park

If these grand developments in the desert suggest that coal and solar are in a close-run contest, they’re not. Before 2016, Pakistan had a single coal-fired plant. It now has nine, supplying 15% of the nation’s electricity, with another four under construction. Solar power provides about 1% of energy needs and is getting a tiny sliver of investment compared with what’s going into coal. Solar and other renewables may someday eliminate Pakistan’s dependence on coal, but that day is probably decades away.

And that’s fine as far as Akhtar Mohammad is concerned. “Coal is good. It’s cheap,” he says at his roadside kiosk in Port Qasim on the outskirts of Karachi, where air pollution is “among the most severe in the world,” according to the nongovernmental Pakistan Air Quality Initiative. He sells sweets, sachets of Head & Shoulders shampoo, and other basics in the shadow of transmission lines that carry power from a new electricity plant that burns imported coal. What about carbon emissions? He shrugs. “This is a small problem,” he says. “There is a lot of smoke and bad air already. We need electricity—any fuel, it doesn’t matter.”

Mohammad’s pragmatism sums up the planet’s quandary. “Coal is the absolute No. 1 cause of carbon emissions globally and the leading driver of climate change,” says Tim Buckley, Sydney-based director of energy finance studies at the Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis. But though wealthy nations may be able to afford to wean themselves off the combustible carbon that’s one of the biggest contributors of greenhouse gases, in countries where electricity is scarce, unreliable, or unaffordable, local politics often takes precedence over economics: Coal remains the cheap fallback.

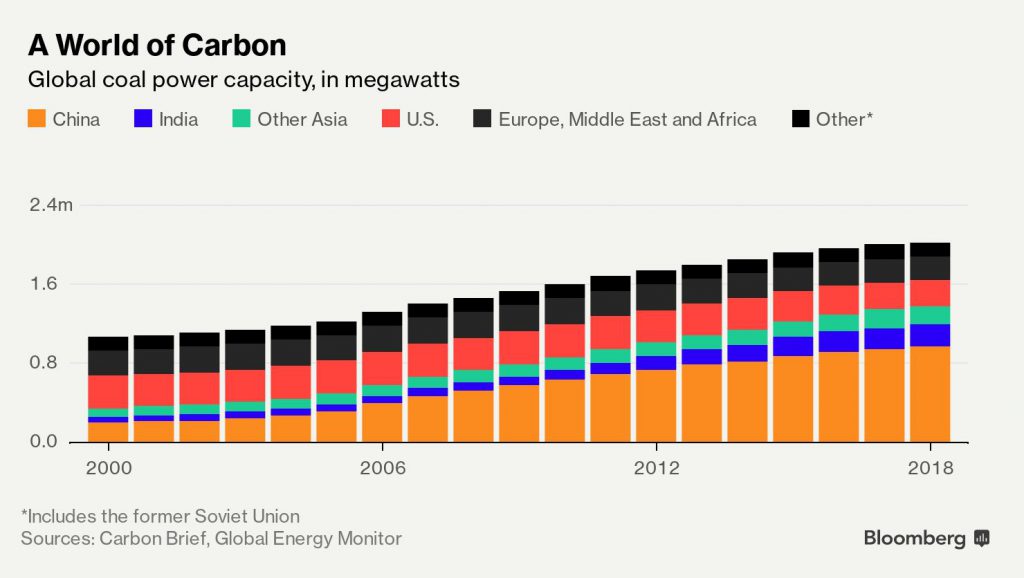

Especially in Asia, dozens of coal plants have come on line in recent years or are in the planning stages—with a normal lifetime of almost a half-century. In South and Southeast Asia, coal burning is expected to increase about 3.5% a year for the next two decades, according to the International Energy Agency. Globally, the IEA predicts, coal demand won’t peak until 2040. And that may be optimistic. Forecasts such as the IEA’s often assume governments will choose the cheapest option based on optimum efficiency while factoring in environmental constraints and the falling cost of solar and wind power.

The world grew up on coal. People in China burned it to smelt copper 3,000 years ago. Britain used it to power the boilers of the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s. In the 19th century, Americans shoveled it into locomotives to connect the country. When Thomas Edison built the first power station for his electric lightbulbs in 1882, it was fired by coal.

And now? Coal consumption won’t decline as significantly as people think, says Shirley Zhang, Wood Mackenzie Ltd.’s principal Asia-Pacific coal analyst. On the one hand, annual global seaborne coal trade probably peaked last year at 980 million tons. On the other hand, from now to 2040, it will decline by only 20 million tons, she says. Despite the rise of renewables, the roll call of governments adding coal-fired plants includes four of the world’s five most populous nations: China, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan.

“Coal consumption won’t decline as significantly as people think”

Wood Mackenzie coal analyst

In 2018, when global carbon emissions rose 2.9%—the biggest jump in seven years—China, India, and the U.S. accounted for two-thirds of the increase, according to BP Plc’s 2019 Statistical Review of World Energy. As developed nations retired coal plants producing 17 gigawatts of power, consumption and production of coal advanced in Asia at the fastest rate in five years. (Michael R. Bloomberg, founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, in June launched an effort to phase out every U.S. coal-fired power plant by 2030.)

Which brings us back to Pakistan. On paper, it could be one of Asia’s top economies. Twice the size of California, Pakistan is home to more than 200 million people between the icebound peaks of the Karakorum and the shores of the Arabian Sea, most of them in the fertile valleys of the Indus River and its tributaries that run down the center of the country. But it’s hobbled by corruption, political turmoil, terrorism, and poverty. In July, shortly after the country got its 22nd bailout from the International Monetary Fund, the central bank raised its base rate to an eight-year high of 13.25% amid soaring inflation.

Add to Pakistan’s woes a crippling shortage of energy. Although the government has made progress in tackling the power deficit, blackouts are a way of life. Tens of millions of people aren’t connected to the grid. In 2015 inefficiencies in the power sector cost the economy $18 billion, or 6.5% of gross domestic product, according to a World Bank report. When it comes to power, says James Stevenson, Sydney-based senior director for global coal research at IHS Markit Ltd., “it’s having it or not that matters, not where it comes from. Governments wanting to be elected want people to have electricity. That’s why coal has momentum.”

The sights and sounds at the Sindh Engro mine in the Thar tell you a lot. The coal being scooped out of the ever-deepening hole is soft, brown, and crumbly—lignite, one of the biggest producers of greenhouse gases. Lignite and hard black anthracite generate about twice the level of carbon dioxide as natural gas; gasoline and heating oils fall about halfway between the two.

The workers digging in the mine, where temperatures can reach 50C (122F), are Pakistani and Chinese. In total, China will provide financing—from 50% to 90% of total costs—for $60 billion in projects to upgrade Pakistan’s transport and energy infrastructure, making the South Asian country a standout partner of Beijing’s “Belt and Road” initiative. Of the 10 biggest BRI power projects by capacity, eight are in Pakistan, and five of those are coal-fired.

China is a vivid example of the rich-poor quandary when it comes to weaning the world off coal. Like many developing nations, it has taken measures to curb climate change, shutting some of its most-polluting steel mills and power plants and relying increasingly on alternative sources. It added more renewable energy last year than all of the 36 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development combined, according to the BP report.

But at the same time, China is the world’s largest producer and user of coal. It’s helping to pay for and build power plants in at least a dozen countries, and though many are solar, wind, natural gas, and hydro projects, the bulk of the Chinese investment is in coal. That doesn’t bode well for the 2016 Paris Agreement on climate change, in which almost 200 nations, including China, pledged to take steps to limit the increase in global average temperature to well below 2C. That commitment basically requires the phasing out of coal: Since the Industrial Revolution, the Earth has warmed by 1 degree and is predicted to at least double that by the end of the century, the fastest pace since the end of the last Ice Age.

It’s not as if Pakistan doesn’t have alternatives to coal. The country’s current natural gas fields are dwindling, but the IEA estimates its shale reserves could contain more than 9 billion barrels of recoverable oil and 105 trillion cubic feet of gas, enough to meet the nation’s needs for decades. It has five nuclear reactors, fed with locally mined uranium, and plans to build two more with Chinese help.

Pakistan is also a regional leader in hydropower. About 29% of its electricity comes from harnessing water, including the massive 4.9GW Tarbela Dam on the Indus River, the largest earth-and-rock-filled dam in the world. Such big structures have come under increasing criticism from environmentalists because of their impact on local ecosystems and populations, but Pakistan plans to build more.

Another problem with hydropower infrastructure is the heavy cost of construction, which is hard to pay for without international support. Pakistan’s proposed $10 billion-plus Diamer-Bhasha Dam, upstream of Tarbela, has held at least five groundbreaking ceremonies over the decades without ever scoring enough financing to proceed.

Meanwhile, Pakistan is pursuing renewable options that require less startup capital. The government of Prime Minister Imran Khan has set a 2030 target to generate 30% of the nation’s energy from large hydro plants and another 30% from other renewable sources that currently supply only about 4%, including arrays of wind turbines springing up along the coast in Jhimpir.

At the forefront of that plan is the Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park in the Cholistan Desert. Originally envisioned as a 1GW plant, it is also backed by Chinese money and technology. The first 100MW started flowing to the grid in 2015, and a contract for the remaining 900MW was awarded to a unit of Chinese telecommunications giant ZTE Corp. with the aim of completing the project by 2016.

But the park has been dogged by controversy—over the award of the contract, allegations of misappropriation of funds, and questions about its efficiency. So far, ZTE’s Zonergy Co. has added only 300MW after the government reduced the price it agreed to pay for the power. Syed Faizan Ali Shah, Zonergy’s deputy general manager for marketing and technical sales, says expansion stalled because the government changed the way it sets prices, which have fallen from 14¢ per kWh to about 6¢ since 2015. Scrutiny of past deals increased after the Khan government came to power last year, including an investigation by the National Accountability Bureau, which also probed two coal-power projects.

Like all solar plants, the one at Quaid-e-Azam is at the mercy of environmental whims, such as variations in sunlight. It faces particular challenges as well, including the frequent dust storms off the Cholistan: If the panels aren’t regularly cleaned, the accumulation of dust can drastically slash the plant’s average power output. According to local media reports, doing the job could require up to 10 million liters of water a year—enough to meet the annual needs of 9,000 people. Shah says the panels only need to be cleaned about twice a month to meet company benchmarks.

In contrast to the stuttering start of Pakistan’s renewable ambitions, the view of the future from the Thar coal mine is one of confidence. “When people talk about coal plants getting shut down or people moving away from coal, they don’t understand what’s happening,” says Ahsan Zafar Syed, chief executive officer of Engro Energy Ltd., the Pakistani company leading the project. “Coal plants that are getting shut down have outlived their useful life. As I speak, there are 26 countries in the world where coal power plants are being constructed. They are everywhere.”

(By Adam Majendie and Faseeh Mangi)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments