One of world’s dirtiest oil sources wants to go green

One of the most aggressive campaigns to fight global warming is happening in a Canadian province. There’s just one problem: the same place is also home to some of the dirtiest oil in the world.

Alberta is boosting its use of renewable energy, closing power plants that burn coal and in January increased its tax on carbon emissions by 50 percent, moves that will help Canada curb emissions under the global Paris climate agreement. However, the province is also increasing output from its vast reserves of oil sands, a gooey fossil fuel that produces more than twice as much carbon dioxide during extraction and processing than the North American average.

This kind of dual personality underscores the dilemma faced by oil producers that are also seeking to control air pollution. Canada in 2011 pulled out of an earlier international climate deal, the Kyoto Protocol, after its oil sands drove up carbon emissions. Alberta’s newly increased carbon tax affects coal and natural gas-fired power plants, but doesn’t apply to its $36 billion oil-extraction industry.

“The oil industry and the government of Alberta were pretty happy to throw the coal industry under the bus because it’s less important to our economy,” said Ian Hussey of the Parkland Institute, a research center at the University of Alberta.

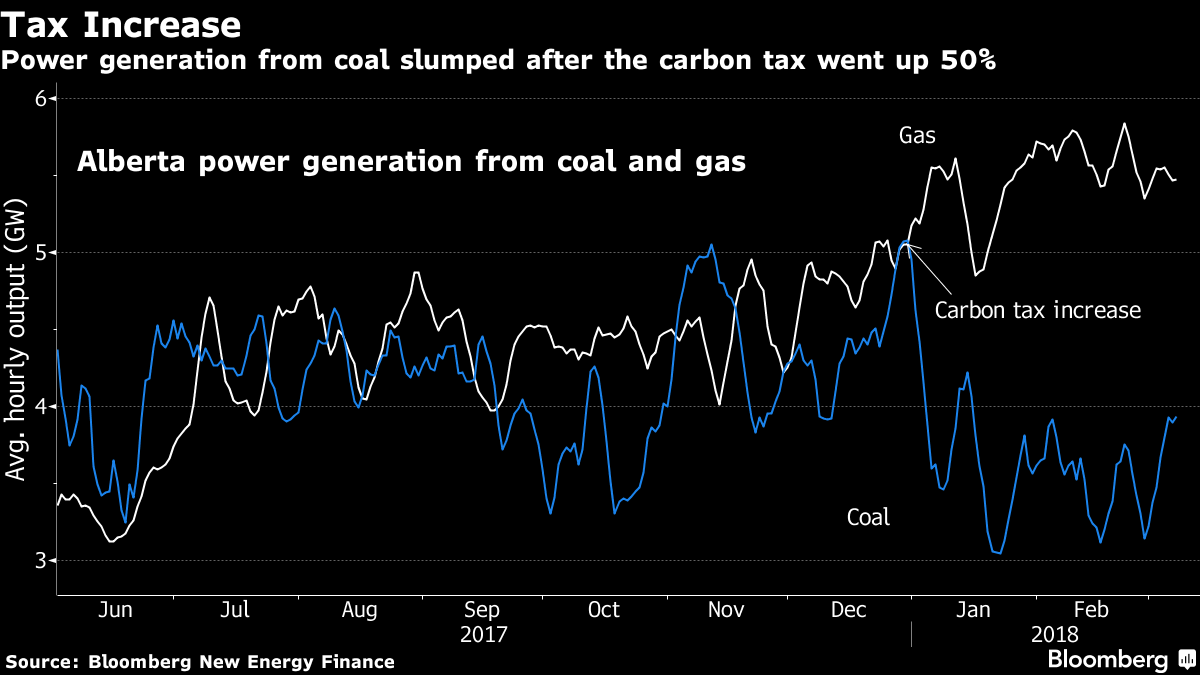

The province in December held its first auction for renewable energy and is preparing to shutter six coal power plants. Its carbon tax on transportation and heating fuels jumped to C$30 ($23) a metric ton on Jan. 1, and promptly spurred a coal-to-gas fuel switch in Alberta, according to a Feb. 14 report from Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

But in terms of environmental benefits, it’s a wash, said Hussey. The reduced emissions from phasing out coal power are “almost exactly the same” as the increases he expects to see from increased oil production.

Alberta’s strategy strikes a “pragmatic” balance after decades of denial and inaction, Shannon Phillips, the province’s minister of environment and parks, said in an interview.

“Carbon pricing is the most market-friendly and most flexible means of dealing with the issue,” Phillips said. “Industry must grapple with — as has happened in Alberta — the fact that climate change is real.”

There’s no way to underestimate the oil sector’s importance. Alberta has the third-largest petroleum reserves in the world and gross revenue from the oil sands were C$36 billion in 2016. Production is projected to grow to 3.67 million barrels a day by 2030, up 53 percent from 2.4 million barrels in 2016, according to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

Places like California and Norway are facing similar issues. While Norway is Western Europe’s largest oil producer and the world’s third-largest gas exporter, it gets about 97 percent of its electricity from hydropower and is the world leader in electric vehicle sales, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

And in California, the fourth-biggest U.S. oil producer, the state government has set a goal of cutting emissions 40 percent by 2030. It’s on on track to get half its electricity from renewable sources by 2020, and three municipalities are pursuing legal fights to hold five five big oil companies accountable for their contribution to climate change.

Back in Alberta, officials must walk a fine line.

“There are always going to be voices that are asking for more action on climate change,” said Phillips. “That’s fine as far as it goes, as long as it is practical and pragmatic in its approach. Otherwise you’re talking about significantly harming ordinary people.”

(Written by Jim Efstathiou Jr and Kevin Orland)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments