No matter how many leaders Australia knifes, renewable energy will still win: Russell

LAUNCESTON, Australia, Aug 22 (Reuters) – Imagine a country that is one the world’s largest exporters of energy but can’t agree on a domestic policy to end electricity blackouts.

Imagine a country on the verge of losing a fourth prime minister within a decade to internal party squabbles, mainly over energy policy.

Imagine a country that is likely to start importing liquefied natural gas (LNG), even though it is about to become the world’s largest exporter of the super-chilled fuel.

The problem for Australia is that this isn’t something being imagined, it’s the reality of a country that can’t find political and social consensus on climate politics and the role of its vast reserves of coal, natural gas and even uranium.

With the National Energy Guarantee (NEG) all but dead and buried, it seems that a comprehensive energy policy will not be delivered any time soon.

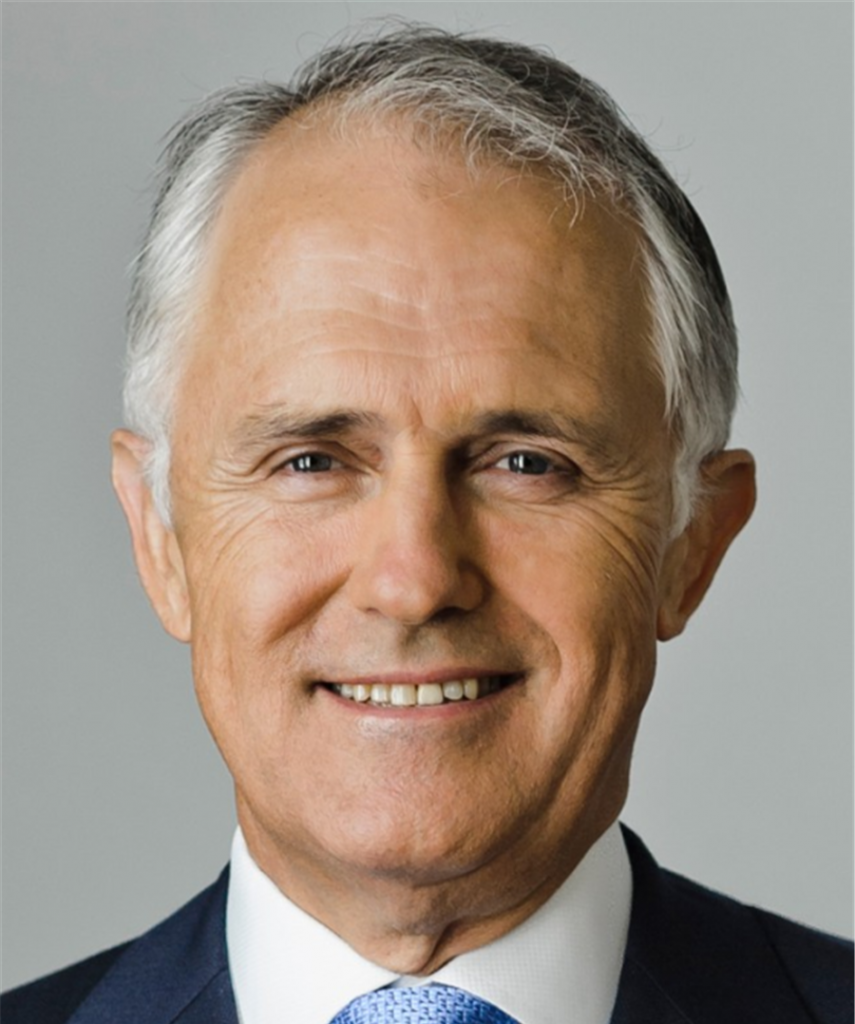

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull narrowly survived a vote this week for the leadership of his Liberal Party, held by the party’s parliamentarians amid in-fighting over his signature energy policy, known as the National Energy Guarantee (NEG).

Turnbull, whose Liberals and junior coalition partner National Party hold a narrow majority in the country’s lower house of parliament, had hoped to use the NEG as the platform to end policy uncertainty over power generation, and ensure that Australia met its obligations under the Paris accord on climate change.

The problem for Turnbull is that a significant number of his party-room are either climate change deniers or sceptics, or strong promoters of the coal industry.

This group already forced Turnbull to scrap the part of NEG which would have legislated emissions reduction targets, effectively neutering a large part of the proposed policy.

While Turnbull survived the party-room vote, most political pundits believe it’s now only a matter of time before his rival, Peter Dutton, gathers enough support to topple him and claim the prime ministership.

Dutton, who quit as home affairs minister after losing the internal vote, was once caught unaware on tape joking about climate change swamping Australia’s Pacific island neighbours through rising seas.

Turnbull appears set to follow in the footsteps of former Labor Party prime ministers Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, and his Liberal predecessor Tony Abbott in being knifed by their own parties.

Rudd, who won a landslide victory in 2007, was dumped in 2009 by Gillard, with part of the reason being his decision to abandon a planned emissions cap and trade system.

Gillard was then toppled by Rudd in 2013, partly because of public anger at rising electricity prices, which then Liberal leader Abbott managed to link to the price on carbon her government introduced.

Abbott won a general election over the resurrected Rudd in 2013, before losing the prime ministership to Turnbull in 2015, mainly because of his rising unpopularity following a harsh budget that was viewed as unfairly targeting those less well off.

While Abbott may not have been axed because of his energy policy, there is little doubt that his plan to reduce emissions by paying polluters not to pollute as much was largely an expensive farce.

Coal to lose out

The upshot is that Australia’s energy policy has been a mess for the last 10 years, at a time when retail electricity prices have more than doubled and the country has experienced wide scale blackouts in the wake of the closure of several old coal-fired power plants.

Under Australia’s federal system, this means the six state and two territory governments will largely be responsible for their own energy policies.

However, there are a few things that are probably clear for the future of energy policy.

Australia on the verge of losing a fourth prime minister in a decade, because of his attempts to deliver an energy policy that reduced the role of coal.

The first is that its highly unlikely a new coal-fired power plants will ever be built in Australia, despite the country being the world’s largest exporter of the polluting fuel, and its role in providing more than 60 percent of current power generation.

No major utility has any interest in investing billions of dollars into a coal plant, especially given policy uncertainty and the certainty of wide-scale public opposition and protests to such a move.

This leaves state governments as the only players likely to build coal-fired generators, and while it is possible they may seek to extend the life of some existing plants, they too would be wary of investing in a fuel that takes the blame for much of the current concern over climate change.

Natural gas also presents problems, given the difficulty in getting the fuel from where it is produced (mainly northern and central Australia) to where it is needed (mainly the heavily-populated southeast).

The last of eight mega-LNG projects is due to start this year, which will make Australia the world’s largest exporter of the fuel.

However, the rapid scaling up of LNG exporters has also meant that domestic gas prices have risen to reflect international LNG prices, and local consumers are struggling to secure long-term supplies under contracts.

This has raised the possibility of LNG imports to cities like Melbourne, Australia’s second-largest and home to much of the country’s manufacturing base.

What initially seemed like a band-aid fix may end up being a structural feature of the LNG market, in which Australia ships LNG to Asia but buys from other countries to meet its domestic needs.

The other thing that appears virtually certain is that the main investment in electricity generation in Australia is going to be in the form of renewables, both large-scale and small, rooftop systems.

Solar and wind farms, with battery backups, are already in existence in South Australia state and several more are planned.

Pumped hydropower using off-peak wind and solar to pump water from a lower reservoir back to a higher one to be used to generate power in periods of higher demand is also likely, with extensions to existing projects in Tasmania state and the Snowy Mountains that straddle Victoria and New South Wales states.

The seemingly ever-rising retail power bills are also driving consumers to rooftop solar with battery storage, which could result in lower demand from the grid but also could serve as a back-up for the grid assuming consumers are encouraged to make their excess power and battery storage available.

The coal proponents circling Turnbull like sharks don’t seem to realise or care that their preferred fuel is likely to be replaced over time, not only by cheaper alternatives but also by a community that can see first-hand the devastating effects of climate change, as witnessed by the drought currently gripping much of Australia.

(By Clyde Russell; Editing by Joseph Radford)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments