Newmont is right to be reserved about Barrick

There are short- and long-term reasons why Barrick Gold Corp.’s latest approach to Newmont Mining Corp. has fallen on deaf ears.

The short-term one is straightforward. As my colleague Liam Denning wrote on Monday, even if you believe some rubbery synergy estimates, the $17.8 billion deal just didn’t look very generous to the shareholders of Colorado-based Newmont that Barrick Chief Executive Officer Mark Bristow is trying to woo.

The ore reserves of a combined Newmont-Barrick would run to about 128 million troy ounces, more than the central bank gold holdings of Germany.

Long-term considerations would seem to argue against that, though. It’s true that Toronto-based Barrick’s proposed share-exchange ratio would see Newmont shareholders bought out for about $1.6 billion less than their company is worth, based on stock prices on the eve of the deal.

Still, next to the $6.9 billion of free cash flow the two companies are forecast to produce over the next three years alone, the number looks rather small. Or consider mining firms’ decade-long scales, where a switch between a 5 percent and 10 percent discount rate can change the value of an individual pit by billions of dollars.

The ore reserves of a combined Newmont-Barrick would run to about 128 million troy ounces, more than the central bank gold holdings of Germany. An investor who walked away from such a deal might be no smarter than one who, say, refused to buy Apple Inc. in 2002 because its price-earnings ratio was too high.

Well, up to a point. There’s a long-term reason why a deal doesn’t offer much to Newmont shareholders, too: It doesn’t give them anything they want that they don’t already have.

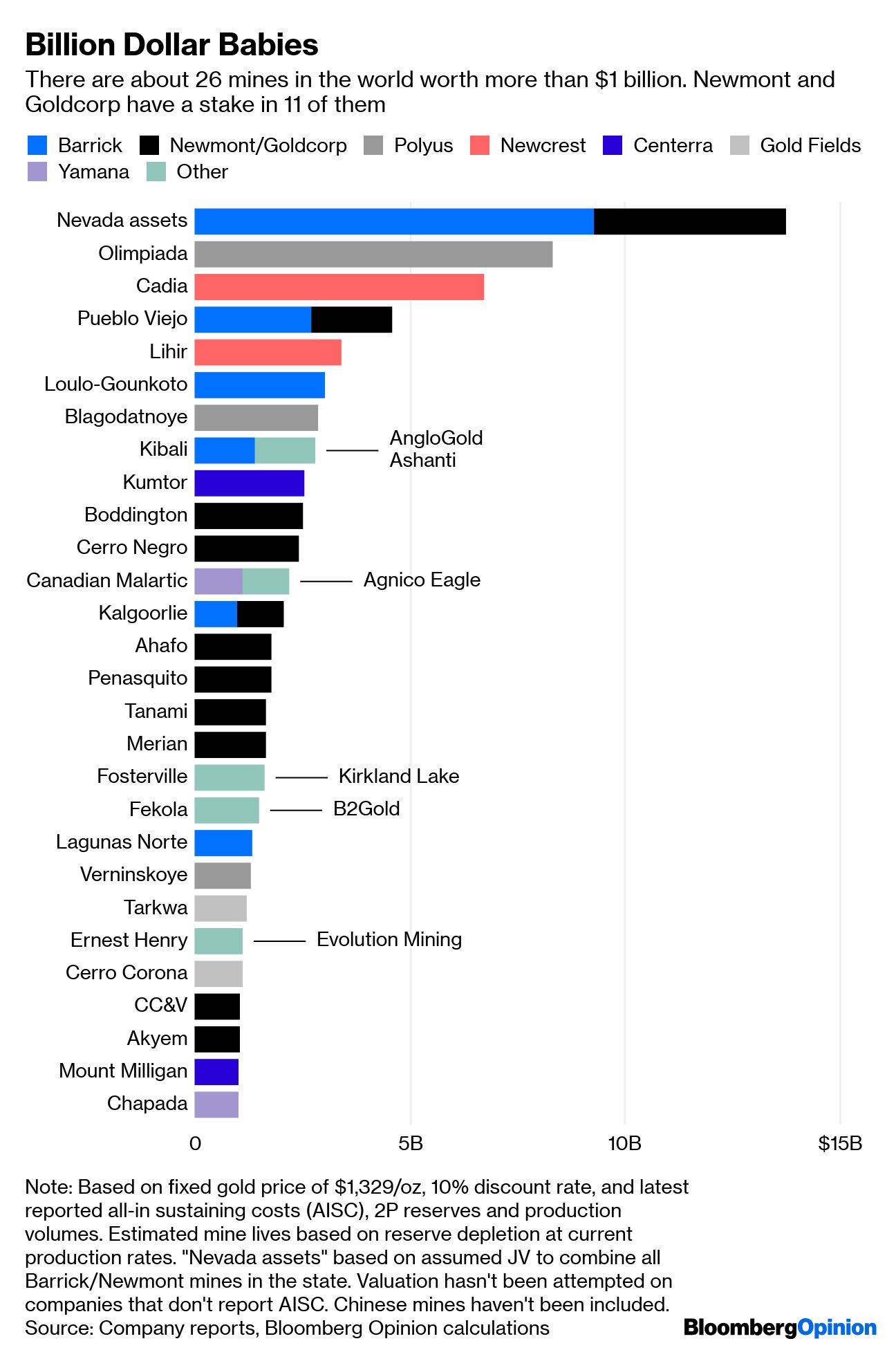

You can get an idea of this by doing a rough discounted cash flow analysis of the world’s big mines. By our estimate, there are no more than about 30 that are worth more than $1 billion at current prices:

At the top is the sprawling group of mines that the two companies operate in Nevada. One of these – the high-grade, long-life Turquoise Ridge pit – is already a joint venture between them, and both sides ultimately want to do the same to the rest of their pits in the state. Such a deal would create the most valuable gold mining complex in the world, worth around $14 billion at current gold prices and a 10 percent discount rate – more than the entire market capitalization of Newcrest Mining Ltd., the third-biggest gold miner by reserves.

What’s left after that, though? The Barrick-controlled Pueblo Viejo in the Dominican Republic is another star mine, but Newmont is already on track to get its share of cash flows via the planned takeover of Goldcorp Inc., which owns the remaining 40 percent. The same goes for the aging Kalgoorlie project in Australia, a 50-50 venture between Barrick and Newmont.

Beyond those, the asset base is looking rather threadbare. Barrick’s remaining large mines are either high-cost (Porgera, Veladero, Hemlo); in less-attractive jurisdictions (its Tanzanian mines and other African pits inherited from Randgold) or both (Porgera). Peru’s Lagunas Norte, in some ways the best of the remaining bunch, is eating through its reserve base so fast that Barrick was trying to sell it until a few months ago.

Buying another company’s assets doesn’t really change that deteriorating situation, so Newmont’s management is probably right to be skeptical. Its shareholders seem to agree, and drove the stock down 6.7 percent in the first three days since the proposal was announced.

Bristow has built a reputation as a great developer of new mines, and there are some 89 million ounces of resources on Barrick’s books that aren’t considered economic enough to classify as reserves. Perhaps he should start working on that pile of rock before running his ruler over another company’s books.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments