New king of copper trading sees demand coming back stronger

As head of copper trading at Trafigura Group, Kostas Bintas typically spends his time trekking around the globe, signing the deals that last year helped make Trafigura the biggest merchant of one of the world’s most crucial metals.

By March this year, he was stuck holding video calls with clients and colleagues from his home in Geneva. With the world on lockdown, the outlook for most industrial metals looked bleak. Yet even then, Bintas says there were early signs copper could emerge from the crisis even stronger.

“Copper is coming out of this crisis differently”

Kostas Bintas, head of copper trading, Trafigura Group

If anything, he’s even more bullish today. Demand is bouncing back in China and stimulus packages being unleashed across the developed world promise to transform the long-term outlook — particularly with spending on copper-intensive green energy infrastructure. The coronavirus has also disrupted mines and delayed new builds, throttling current and future supply.

“Copper is coming out of this crisis differently,” Bintas said by phone from Geneva. “When lockdowns were eased and people started to return to work, we were surprised to see our customers not only taking deliveries of volumes they’d already bought, but requesting more to cover themselves in case there were any further disruptions to supply.”

Trafigura’s view adds clout to forecasts that the metal viewed as a global economic bellwether is heading for a V-shaped recovery. Not everyone is as bullish, with some forecasters suggesting copper’s rebound risks running out of steam. Yet Bintas has one key advantage: Trafigura’s vast network of traders gathering direct intel from the heart of the copper market.

The company bought and sold 4.35 million tons of copper last year, Bintas said, surpassing rival Glencore Plc as the world’s top trader. A Glencore spokesman declined to comment.

Trafigura’s case for copper

- The virus has forced many mines to halt operations, particularly large operations in South America, and delayed work on future projects.

- Stimulus packages are targeting areas that are highly copper-intensive, such as renewable energy and electric vehicles.

- Climate change is also fueling greater demand for copper-heavy heating and cooling systems globally.

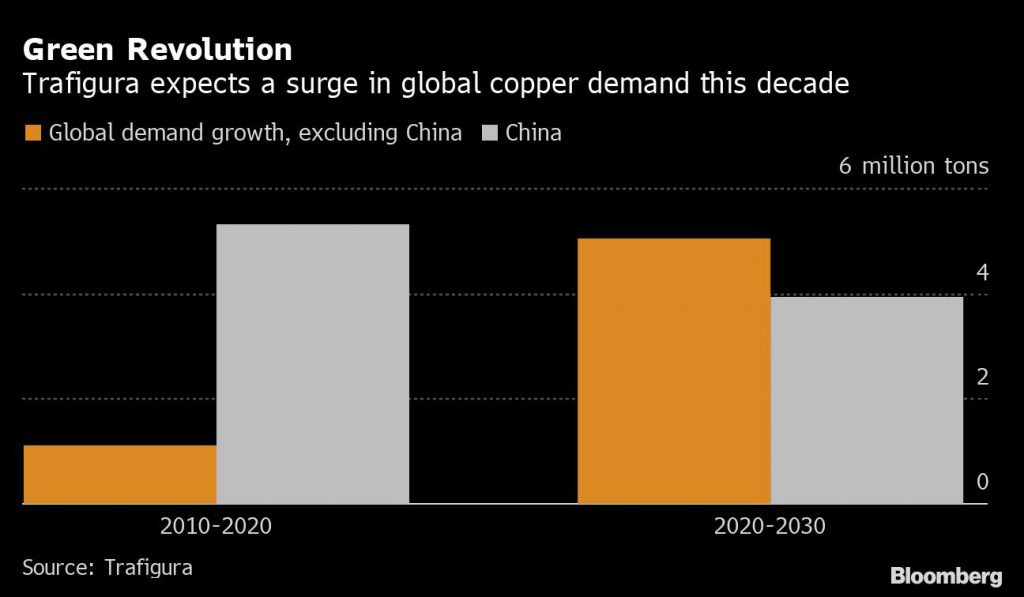

- Demand looks set to rise 3.4% per year in the coming decade, which will push the market into a deep deficit unless new sources of supply are found.

- Given the high costs of development, copper would need to trade above $7,600 a ton to incentivize long-term investments in new mining projects.

- Despite the demand crisis, global visible inventories dropped by 412,000 tons between March and June.

“Despite the noise of what the price is doing or the equity markets are doing, the most important thing is to isolate the signal that you’re getting from customers and suppliers,” Bintas said. “You can’t get more genuine feedback than that.”

While copper prices slumped sharply in January as China went into lockdown, and again in March as the rest of the world followed suit, the metal has since been clawing back losses. Prices rallied as much as 2.3% to $5,906.50 a ton on the London Metal Exchange on Wednesday, the highest in more than four months.

The rebound has been supported by a steady stream of data showing a recovery in demand that Bintas has witnessed in real time.

Trafigura estimates that the virus has reduced mine supply by 400,000 tons, while so far in 2020 scrap availability has dropped about 700,000 tons from levels seen a year earlier. Collectively, that outstrips a 900,000-ton year-on-year drop in demand over the same period.

In a sign of growing tightness, copper scrap supply has dried up so drastically that buyers in China were paying higher prices than for brand-new metal, Bintas said.

“Demand is clearly on a recovery path, while these big supply centers in South America are still under pressure,” he said.

For Trafigura, the coronavirus crisis has reinforced the benefit of its copper-trading muscle. The company and Glencore have both expanded in the business as smaller trading houses, hedge funds and investment banks exited the sector due to a raft of factors, including declining volatility in some parts of the physical market, stricter regulations, and higher costs of financing and staffing a globe-spanning trading team.

In the case of the London-based hedge fund and physical trader Red Kite, which at one time supplied about 15% of China’s copper needs, some fund managers came to feel that having a toe-hold in the physical markets was becoming less useful as a guide to where prices were heading. But with the pandemic putting supply and demand front and center of investors’ minds, fundamental hedge funds are positioning themselves for a revival.

“In terms of the value of having boots on the ground and the right connections, it takes a year like this to prove the point,” Bintas said.

(By Mark Burton, with assistance from Thomas Biesheuvel)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments