Not anymore.

In early May, China implemented a 30-day ban on all scrap-copper imports, part of wider limits on all sorts of imported waste like paper, plastic and scuttled ships. The government wants to clean up decades of pollution from heavy industry and jump start domestic recycling. But without the world’s biggest buyer, U.S. prices dropped and inventories ballooned. Scrap dealers are offering discounts to spark sales at home and lure new buyers in places like Turkey, India, Japan and Malaysia.

At Utah Metal Works in Salt Lake City, where Lewon is president of the family-owned business, stockpiles of unprocessed insulated wire — both copper and aluminum — have doubled from a year ago to about 3 million pounds (1,360 metric tons). Gone are the days when the company would send 1.3 million pounds a month to China, clearing out almost the entire inventory, he said.

“As this material piles up, that’s a cash drain because we’ve paid for it, or we’re in the process of paying for it,” Lewon said in an interview at Bloomberg headquarters in New York. “It’s sitting there. You don’t earn anything on it.”

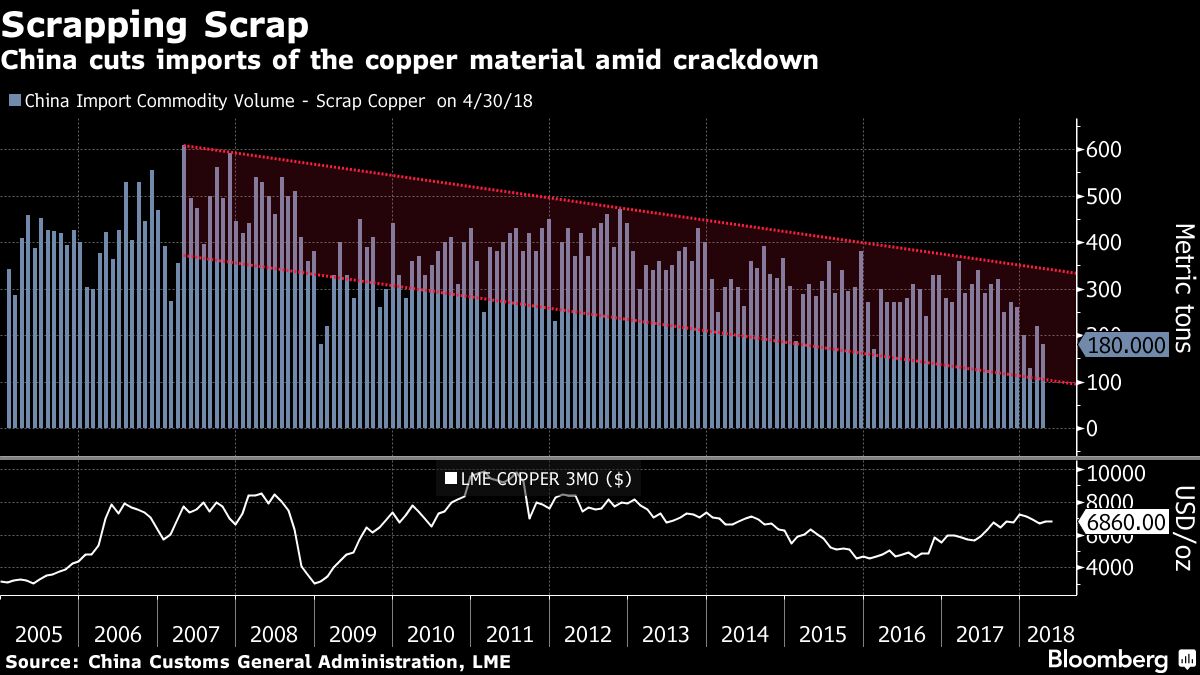

Chinese imports of copper scrap in April were down 38 percent from a year earlier, data from the Beijing-based Customs General Administration show. And purchases are expected to keep dropping as long as the ban remains in place.

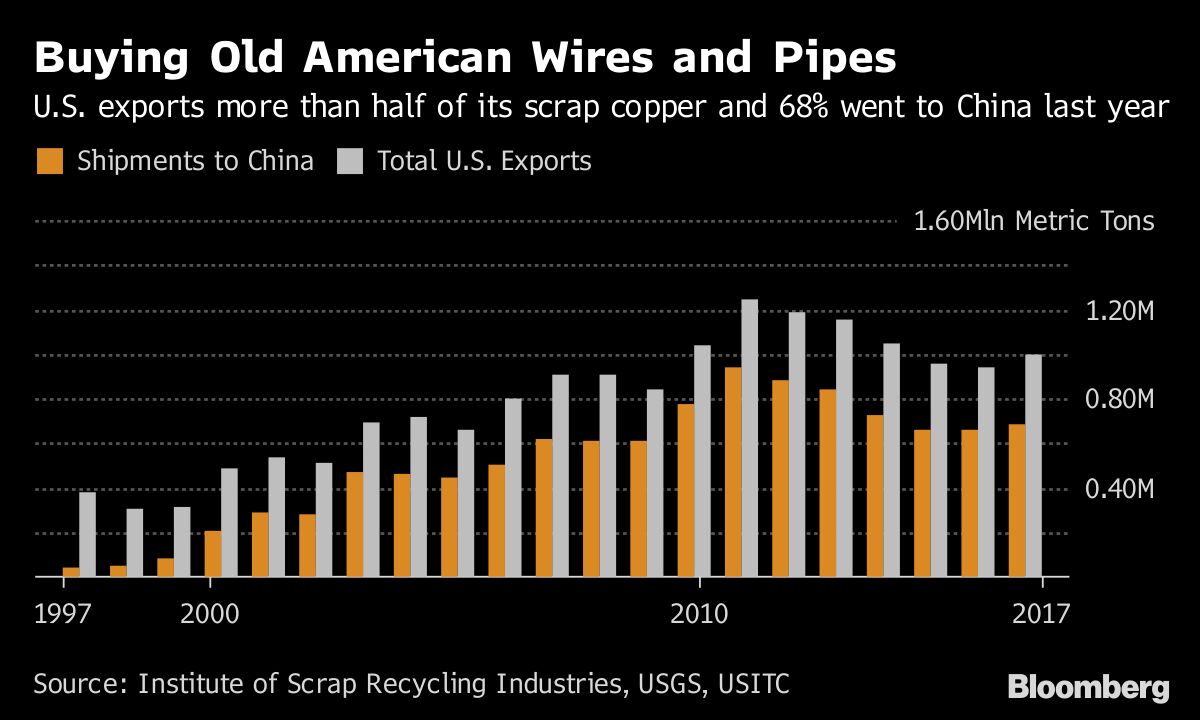

Unless new buyers are found, that would be a big loss for American dealers, who send more than half of all their scrap copper to the Asian country. Last year, the U.S. sold 685,450 metric tons valued at $1.71 billion to China, or 68 percent of all shipments overseas, according to data compiled by the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries. That was up from 11,000 metric tons, or 11 percent of deliveries, in 1997.

Biggest buyer

China altered the landscape of global recycling over the past two decades as its fast-growing economy sparked a spending spree on infrastructure and generated more demand for raw materials than the country could produce. In 2016, it imported about $5.6 billion of scrap commodities from the U.S. including metals like steel and aluminum as well as paper and plastics, according to ISRI. Imports from the European Union totaled 3.9 billion euros ($4.56 billion) last year.

Those trading patterns may be shifting. The country is trying to curb rampant pollution with new restrictions on waste imports and shutting old industrial plants, including mills that process foreign scrap into reusable raw materials. That’s already upended the market for recycled paper.

‘Powerful position’

China says it will no longer accept a category of metal scrap that includes electrical cables, electrical motors and waste hardware. That could mean importing about 300,000 tons less this year, according to analysts at Wood Mackenzie.

“They don’t want to be the world’s dump,” said Tom Buechel, owner of Rockaway Recycling in Rockaway, New Jersey. “They are in a more powerful position to be able to say no, we’ll tell you what we want, and we’ll take it, but it has to be on our terms.”

Prices already are falling. Since the beginning of May, Buechel has been offering his scrap at 10 percent to 15 percent below what he was charging a month earlier.

“While the ban on scrap imports was originally laid out to last 30 days, it could go beyond that,” said Andrew Cosgrove, a Bloomberg Intelligence metals analyst in Skillman, New Jersey. “If that does happen, scrap prices could come under additional pressure and get to the point where recycler profit margins get squeezed enough to limit uptake.”

At Lorbec Metals USA in Flint, Michigan, inventories of lower-grade copper had been piling up for three months until the company was able to export some to Malaysia. President Jay Goldstein, who has been in the business since 1970, said the company now sends about 5 percent of all its scrap metal to China, which includes several kinds, down from 25 percent in years past.

Old wire and cable — considered the most-valuable grade of scrap — is trading at $2.915 a pound, according to Metal Bulletin. That’s a discount of 17.65 cents to Comex futures, which traded at $3.0915 a pound in New York on May 25. A month ago, the spread was 16.8 cents.

Copper futures for July delivery fell 0.7 percent to $3.0425 a pound at 8:43 a.m. Wednesday on the Comex in New York.

The price for No. 2 copper — which includes cable wires and extension cords that are insulated with plastic and carry some degree of corrosion — was about $2.695 a pound delivered to refiners on May 25, Metal Bulletin data show. That’s down from as high as $2.795 a month earlier.

Recycling industry

Reduced purchases by China could pose structural problems for the industry. Recycling has expanded globally as the cost of waste disposal rose and commodity industries sought cheaper sources of new supply to augment production from mines.

“It takes an enormous amount of energy to produce all these metals used in day-to-day life,” said Peter Thomas, a senior vice president at Chicago-based metals broker Zaner Group.

“If you can get scrap, you are no longer pumping as much fuel into the atmosphere. It’s also cheaper to refine and recycle these products, so you’re getting a better cash yield — everyone wins.”

“If you can get scrap, you are no longer pumping as much fuel into the atmosphere. It’s also cheaper to refine and recycle these products, so you’re getting a better cash yield — everyone wins.”

Some scrap dealers are hoping President Donald Trump’s trade negotiations with China will help turn things around.

“The Chinese aren’t playing fair,” said Lewon, a past chairman of the ISRI. The industry group met with U.S. trade representatives and members of the Commerce Department to seek help in reopening the Chinese market, he said.

For now, the strong U.S. economy is easing some of the pain of lost exports. Utah Metal Works expects that China eventually will return as a buyer, even if the country doesn’t import as much as it did before.

“It is still a giant market,” Lewon said. “Ultimately they need our product.”

(Written by Susanne Barton)

Comments