Mpox risks spreading in Congo’s crowded mines, refugee camps

For medical and aid workers scrambling to contain an outbreak of mpox on the Democratic Republic of Congo’s eastern flank, the location couldn’t be worse.

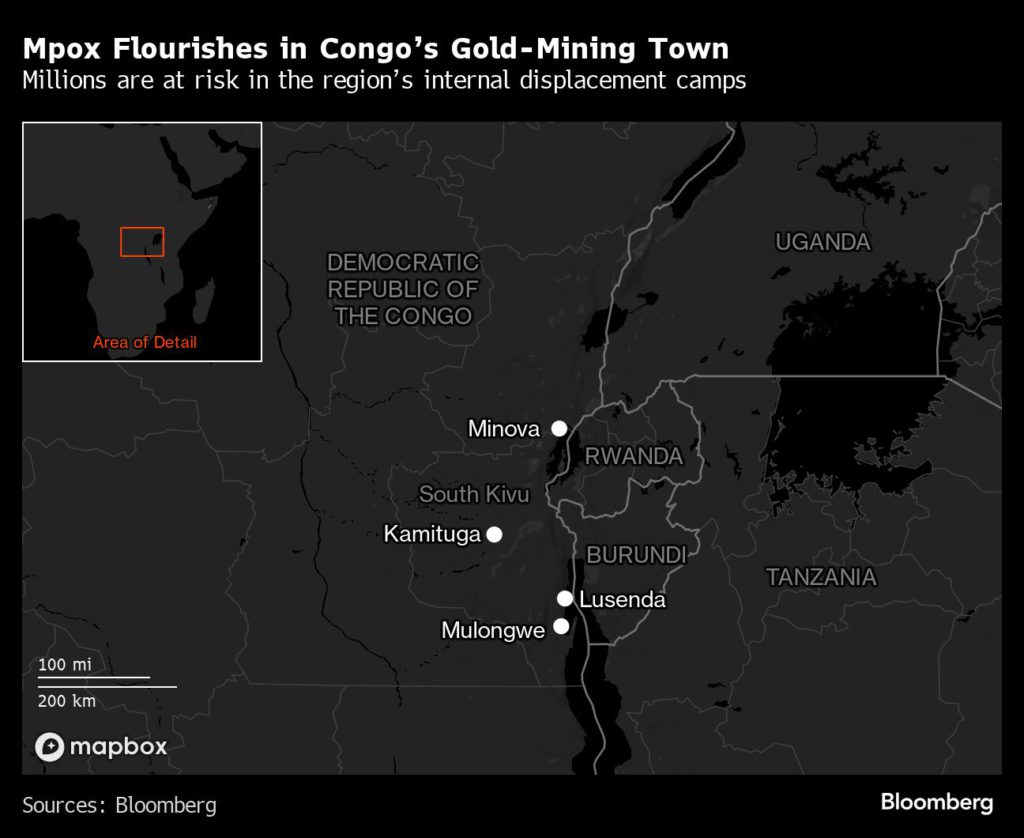

A strain of the virus — which causes lesions that can result in disfigurement, blindness, and even death — has erupted around the gold-mining town of Kamituga, where about a quarter of a million people live.

It’s an area that thousands of small-scale, individual miners travel in and out of, attracting scores of sex workers while truckers ply routes between Congo and the neighboring nations of Burundi and Rwanda, and on to Tanzania.

Add to that the presence of 4.2 million internally displaced people, driven from their homes by years of intermittent conflict. Many of them are staying in crowded camps in the province, South Kivu, and neighboring North Kivu, which is a recipe for the rapid spread of a disease that’s killing the weak and malnourished, often children.

“There are millions of children already displaced and in addition now there is this outbreak of mpox,” said Katharina von Schroeder, director of advocacy and communications at Save the Children, a charity that has 300 staff in the central African country. “The big, big threat is the IDP camps. We are seeing the first cases. People are already very fragile and the fatality rate could be much higher” if it isn’t contained, she said.

The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a global health emergency on Wednesday, amid mounting concern about the rapid spread of the pathogen.

Already this year, about 15,700 cases have been suspected, resulting in around 550 deaths, according to the Congolese government. While many of those are due to an older, less contagious variant, there’s concern that infections from the newer variety will rise exponentially. And the way it’s presenting is problematic.

“We’re seeing a lot of cases among sex workers,” Roger Kamba, Congo’s public health minister, said in a televised presentation on Aug. 15. The variant is dangerous because it’s harder to spot — there are fewer external signs, like the raised buttons on the faces and hands of earlier mpox patients, he said, adding that about 3.5% of those infected have died.

Kamituga is surrounded by verdant hills that feel far removed from the sprawling trading hub of South Kivu’s capital, Bukavu. It’s in a region that Congo’s government has struggled to control since conflict began in the 1990s in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide and the fall of longtime Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. The town has suffered decades of predation by armed groups and at times from soldiers of the country’s own army.

“Frequent travel occurs between Kamituga and the nearby city of Bukavu, with subsequent movement to neighboring countries such as Rwanda and Burundi,” Congolese and other researchers wrote in a paper published by the journal Nature Medicine in June. “Moreover, sex workers operating in Kamituga represent several nationalities and frequently return to their countries of origin.”

While the disease can spread sexually it can also be transmitted through skin-to-skin contact, making children vulnerable. Added to that, Kamba said, is that younger Congolese people have never been vaccinated against smallpox, a related disease that’s been eradicated. Immunizations against that disease provide protection against catching mpox.

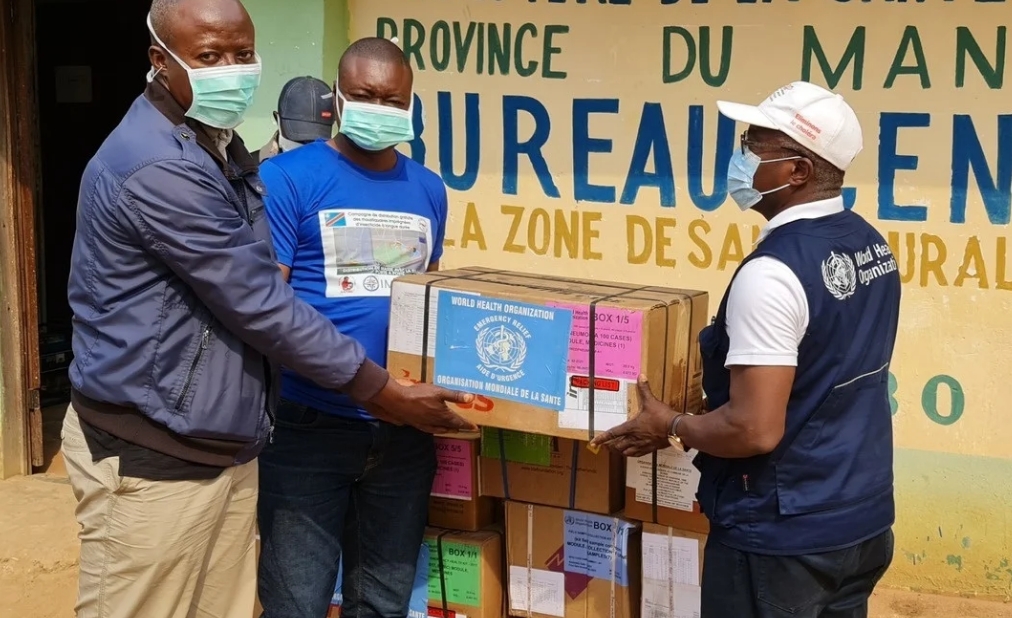

For now aid agencies such as Save the Children and Unicef are focusing on awareness campaigns, so that people in the region where the disease is most prevalent know of its presence and how it spreads, and supporting woefully under-resourced health facilities.

“We are raising knowledge, raising awareness within the population. If a family member gets sick people still go and visit” and the infected aren’t always separated from the uninfected at medical facilities, Von Schroeder said. “The health systems are completely overwhelmed.”

Mpox is not a new disease. It’s been spilling over from animals into human populations in parts of west and central Africa, such as heavily forested Congo, with increasing frequency since the 1970s.

“We have to take that into account,” Kamba said. “We’re in a relationship with animals in relation to diseases.”

But human-to-human transmission, as seen with the latest variant, heightens the danger of a debilitating outbreak.

The next steps will be getting sufficient vaccines to the region. Kamba estimates that 3.5 million doses will be needed and that will cost hundreds of million of dollars, money that Congo, one of the world’s poorest countries, doesn’t have.

While Congo has dealt with other outbreaks before including Ebola, cholera and measles, those have weakened its health systems.

If this outbreak is to be tackled effectively there needs to be a solid vaccination plan once shots reach the area.

At about $100 per dose, the vaccines are currently very expensive and many countries in Africa can’t afford the cost, according to Jean Kaseya, director general of Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Mpox is a slow-burning fire that has been allowed to smolder in central Africa and is flaring up,” said David Tscharke, a poxvirus researcher at the Australian National University’s John Curtin School of Medical Research.

(By Antony Sguazzin, Michael J. Kavanagh and Janice Kew)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments