The market arranged Newmont’s Goldcorp marriage

Gary Goldberg isn’t pulling the trigger on a $10 billion gold-mining acquisition because he has to, you know. The CEO of Newmont Mining Corp. said Monday morning of his acquisition of Goldcorp Inc.:

Simply put, this is not a deal we have to do. This is a deal that we want to do.

Sometimes, though, one’s choices are influenced by the choices of others. In this case, Goldberg can’t have failed to notice strong hints from the market.

This round of consolidation — Newmont’s move follows a Randgold Resources Ltd. deal with Barrick Gold Corp. announced in September — puts me in mind of the mega-mergers in the oil industry 20 years ago. Back then, there was a flurry of deals to create supermajors like Exxon Mobil Corp. With oil prices having collapsed in 1998, the industry saw self-help in the form of cost-cutting and high-grading of portfolios as the path to redemption — and it was (aided by an enormous rally in oil, of course).

Gold miners aren’t reeling from a collapse in the metal’s price. Gold is down roughly a third from its 2011 peak, but has traded sideways for much of the past five years. Like those oil majors of the late 1990s, though, the miners need to do something to spark some interest in their stocks. As a group, they have suffered especially from the rise of gold-backed exchange traded funds, which offered goldbugs purer exposure to the precious metal. In theory, the miners had a counteroffer of leveraged exposure, with the prospect of margins soaring on more modest increases in the underlying gold price. Yet, like the metal itself, costs appear to have flattened out.

Flat costs would be great if gold itself were due for a big rally, but there’s not much money betting on that. Consensus forecasts have gold ranging between $1,270 and $1,300 an ounce over the next four years, which is where it is now. Holding gold has been a lousy proposition over the past five years compared not just with stocks but also Treasuries. While the broader panic at the end of 2018 revived some interest in the metal, that came after speculative net length in gold futures being in free fall for much of 2018:

Mark Bristow, previously CEO of Randgold and now running the enlarged Barrick, has justified that deal by warning the industry risked becoming “irrelevant” if it didn’t do something. It surely wasn’t lost on Newmont that stocks in both of those companies soared after they announced their deal.

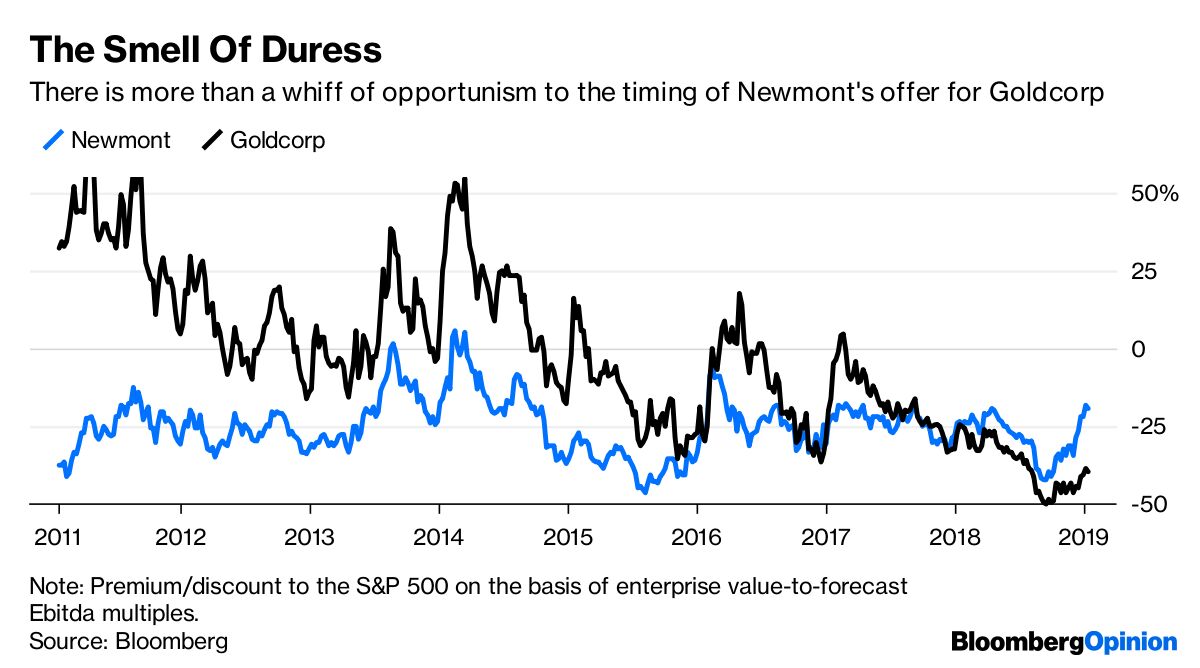

It likely also wasn’t lost on Newmont that Goldcorp’s valuation was in the pits. Having historically traded at a premium to the market, by September it had dropped to its lowest relative valuation in years.

Unlike the Barrick-Randgold deal, Newmont is paying a premium in this virtually all-paper offer. And at $1.5 billion, that’s three times the value of the touted cost-synergies, net to Newmont’s existing shareholders’ pro forma stake in the combined entity. Unimpressed, investors have chopped about $1.7 billion off Newmont’s own market cap as of Monday afternoon.

That may be overly harsh, as high-grading the combined portfolios should provide additional savings and the opportunity to cash out on some lower-tier assets. But it’s also a reminder that this deal, and those all but certain to follow, arise more from necessity than choice.

(By Liam Denning)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments