Major operational overhaul planned for KSM copper, gold mine

A massive gold-copper mine planned for northwest B.C.’s Golden Triangle would have a higher capital cost but lower operating costs and a smaller environmental footprint, according to a revised plan.

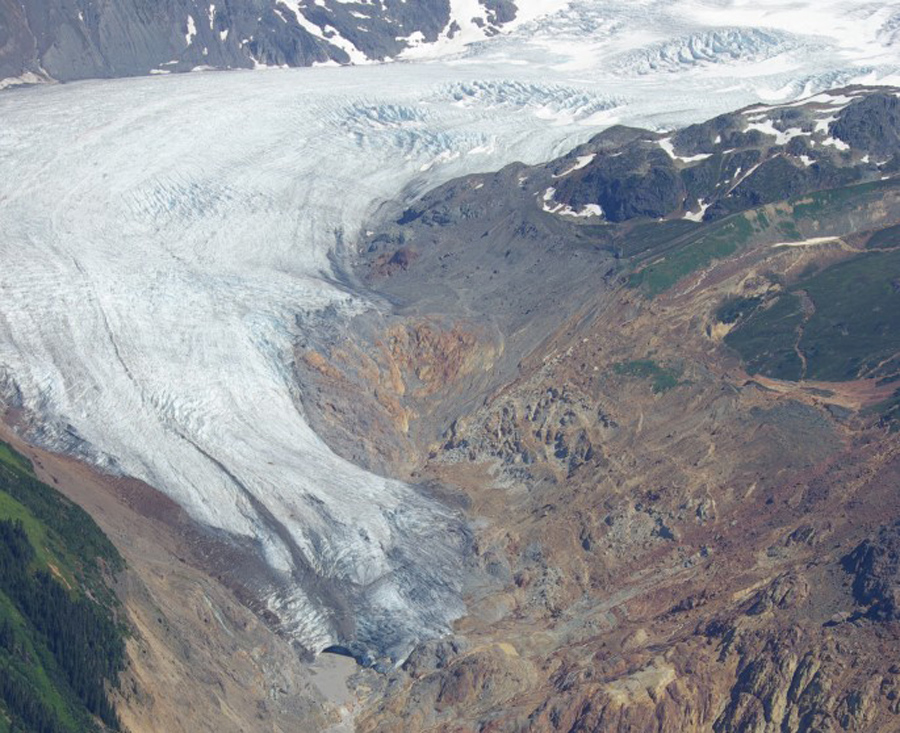

Seabridge Gold Inc. (TSX:SEA) recently updated its plans for the proposed Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell (KSM) mine 65 kilometres northwest of Stewart with a preliminary economic assessment and an updated pre-feasibility study that recommend block cave mining, an approach that would shrink the scale of open-pit mining to 22% from the 70% initially proposed and reduce the volume of waste by 2.4 billion tonnes.

It would also increase annual copper production to 170,000 tonnes from the original estimate of 130,000 tonnes.

The change in plans will add 10% to the initial capital costs estimated in the updated pre-feasibility report: $5.5 billion from $5.3 billion.

During the first seven years of operation annual gold output would top 1 million ounces.

But thanks to a low Canadian dollar, the project would have a lower capital cost – in U.S. dollars – than estimated in the 2012 pre-feasibility study, when the Canadian dollar was at par with the greenback.

“The strong exchange rate makes them look lower in U.S. dollars,” said Sid Rajeev, a mining analyst with Fundamental Research Corp.

The base case per-ounce capital costs to build the mine were estimated at US$673 in KSM’s pre-feasibility study. The new base case costs are now estimated at US$358 per ounce, thanks to the increased copper production.

“Five billion is still huge,” Rajeev said. “But one of the benefits of this project is that it has a lower operating cost.”

The mine received its environmental certificate from the B.C. government in 2014 and recently received a permit to build an exploration adit (the angled horizontal shafts used in block cave mining).

“This project is about volume and a low geopolitical risk jurisdiction that’s already permitted,” said mining analyst Joe Mazumdar, co-editor of Exploration Insights. “Those are the positives.

“The negatives [are] footprint, the high upfront capital and the infrastructural challenge of what you’ve got to do. It’s not an easy, low-execution risk build. It’s a pretty big project.

“It’s hard to get a decent IRR [internal rate of return] out of a $5.5 billion upfront capital project.”

The KSM project is said to be the world’s largest undeveloped gold-copper project. It’s made up of four deposits that would be mined and processed in two distinct operations 23 kilometres apart and connected by twin underground tunnels.

The KSM has proven or probable gold reserves of 39 million ounces and 10 billion pounds of copper, plus some silver and molybdenum.

Building the mine would create 1,800 direct and 4,770 indirect jobs over a five-year construction period, and 1,040 permanent jobs over a 52-year period, according to Seabridge.

By moving to block cave mining for some of the deposits, the environmental footprint shrinks in more ways than one. The approach reduces the amount of surface disturbed through open-pit mining and the amount of waste rock that would otherwise be produced. That in turn reduces the amount of waste that would need to be treated to prevent acid rock drainage. But such a big project would require equally big partners to enter a joint partnership or buy Seabridge outright, which would add about $1 billion to the total cost.

The world’s largest mining companies need to continually add production capacity, and Rajeev said there are few large undeveloped projects like KSM yet to be acquired or developed.

But many of the world’s biggest players took massive write-downs in the last mining supercycle. Some have been chastened for investing in massive projects with marginal ore qualities and failing to return value to shareholders at a time when commodity prices were high.

The trend today is to invest in smaller, higher-quality projects. So unless commodity prices get a significant lift, Rajeev said it’s unlikely that even the big players like Rio Tinto (NYSE:RIO) or BHP Billiton (NYSE:BHP) could finance such a large project.

“The market has not improved that much to make this project attractive yet,” he said.

The only players that might have the wherewithal to finance such a large project are the Chinese, Mazumdar said.

“In terms of western companies, on the gold side, I don’t see a lot of companies being interested in a big capital project right now.”

To date, Seabridge has spent $176 million on the KSM project. In 2015, the company’s share price dipped as low as $4.55, along with the general downturn in the mining sector.

It has since rebounded, as the commodity prices and investment sentiment in mining improved, reaching nearly $20 in July. Last week, the company’s stock was trading in the $14 range.

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments