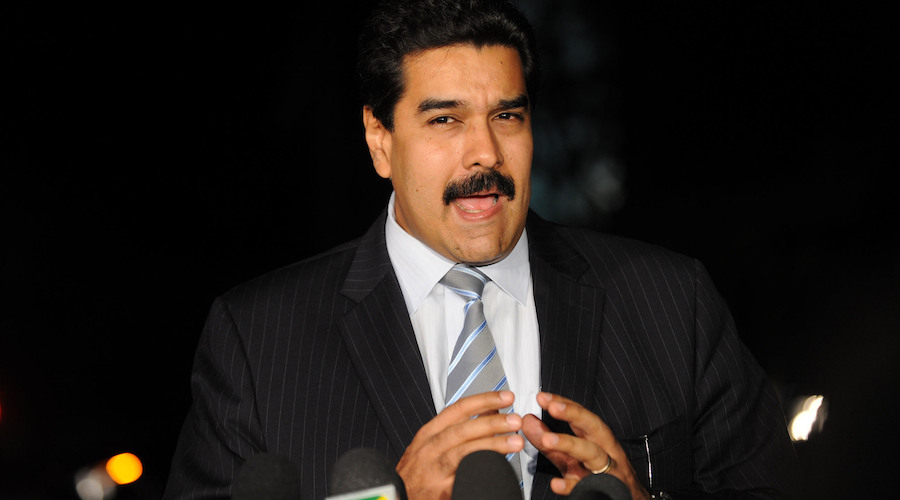

As Maduro digs in, his aides hunt for emergency escape route

Nicolas Maduro is under pressure at home and abroad, and being encouraged by the U.S. to go to “a nice beach somewhere far from Venezuela.” The question is where would — or could — he go?

The Venezuelan leader has held on for years in the face of protests, a collapsed economy and international sanctions, via a tight grip on the military and by cracking down on the opposition. But the stress has never been greater. The financial noose is tightening globally, many neighbors and western nations are calling on him to hold elections or step aside, and the opposition has galvanized under Juan Guaido into a more cohesive force.

Maduro has insisted publicly he’s going nowhere and a departure could be several steps away, if it happened at all. He has spoken frequently to denounce what he says are U.S.-led coup efforts against him, and all signs are he is digging in. Still, contingency plans are being drawn up in case he needs to leave Venezuela at short notice, according to four people with knowledge of the discussions.

Any potential safe havens bring risks, both for Maduro and the countries involved. While the U.S. has said he should leave, it may not take too kindly to any nation that gave him sanctuary. And Maduro would want to feel safe from the reach of Venezuelan and international law.

Some unsurprising destinations are being discussed, including Cuba, Russia and Turkey. In Cuba, the communist government of Miguel Diaz-Canel is an ideological ally to Maduro’s Bolivarian republic.

Russia, a traditional ally, is showing signs of doubt over Maduro’s ability to hold on to power.

Some conversations have also taken place about the possibility of him going to Mexico, two of the people said, asking not to be identified given the sensitivity of the matter. President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador is one of a handful of Latin American leaders not to have recognized Guaido, the National Assembly leader, as Venezuela’s rightful president. Maduro attended Lopez Obrador’s inauguration in December.

Discussions have been stepped up because Maduro’s wife Cilia Flores — who has two nephews serving 18 years in a U.S. prison for conspiring to traffic cocaine — is raising pressure on her husband to have a plan B ready, another person said. Venezuela’s information ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

“I think it is better for the transition to democracy in Venezuela that he be outside the country,” Elliott Abrams, U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo’s special representative for Venezuela, said of Maduro. “And there are a number of countries that I think would be willing to accept him,” he told reporters, citing “friends in places like Cuba and Russia.”

The fate of Maduro, his family and top lieutenants is key to any transition of power in Venezuela, an OPEC member whose population is suffering chronic shortages of food, medicines and basic amenities. A summit of European and Latin American countries held in the Uruguayan capital Montevideo last week agreed to work toward a peaceful political process that leads to new presidential elections in Venezuela.

Speaking in Washington last week, Abrams said that countries other than Russia and Cuba “have come to us privately and said they’d be willing to take members of the current illegitimate regime if it would help the transition.” He declined to name them.

“It’s not in our rules to give up our own — and he is still one of ours”

Any flight to Cuba by Maduro or his people would give the U.S. justification to put Havana back on the radar, said a person familiar with the thinking, citing the potential for evidence linking some officials to drug or weapons trafficking in the region. It would allow Washington to push ahead with a package of extraordinary measures targeting Cuba for encouraging state-sponsored terrorism across the region, the person said.

Jorge Rodriguez, Venezuela’s communications minister, was in Mexico last month around the time of a visit by Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez. One person said the topic of possible escape routes had come up late last year.

Roberto Velasco, the spokesman for Mexican Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard, said that Lopez Obrador’s government and the Maduro administration haven’t discussed asylum. A spokesperson for Sanchez wasn’t immediately available for comment.

At his daily news conference on Friday, Lopez Obrador reiterated his government is guided by the constitutional prohibition on intervening in the affairs of other nations but would be open to helping mediate a dialogue between the two sides in Venezuela.

Mexico has a long tradition of granting asylum to foreign leaders. The Shah of Iran, who fled during the revolution in 1979, took refuge in the resort city of Cuernavaca, with former U.S. President Richard Nixon coming to visit him. Soviet Marxist Leon Trotsky, who became an exile after clashing with Joseph Stalin, moved to Mexico in 1937 and was welcomed by leftist President Lazaro Cardenas, who is a hero for Lopez Obrador.

There is the possibility Maduro could seek refuge further afield if he decided to leave. A French official said the issue of Maduro’s fate is under active discussion in the international community, though a solution has yet to be found.

An added complication surrounds what to do with the vice president of Maduro’s United Socialist Party, Diosdado Cabello, according to another person with knowledge of the deliberations. Prosecutors in the U.S. have been compiling evidence against Cabello since at least 2015 on alleged drug trafficking, as the Wall Street Journal and Spanish daily ABC reported at the time.

The air is getting thinner for Maduro either way. The economy is in free fall, oil exports are subject to U.S. sanction, rank-and-file soldiers are deserting the military, while the International Monetary Fund said that it sees hyperinflation and outward migration intensifying this year. Russia, a traditional ally, is showing signs of doubt over Maduro’s ability to hold on to power.

Iran Slams U.S. Over Venezuela. Secretly, Some May Be Relieved

Moscow is not fond of Maduro, but has little choice in the matter, according to a person with knowledge of the internal discussions who spoke on condition of anonymity. The Kremlin won’t encourage him to flee unless there is a clear alternative — and for Moscow that is not Guaido, the person said.

“He is not planning to go anywhere,” Russian lawmaker Andrey Klimov, deputy head of the upper house of parliament’s foreign affairs committee, said by phone. He dismissed talk of Maduro’s evacuation as “psychological warfare” aimed at “sowing panic and hysteria.”

“I think Maduro and his people are more likely to become guerrillas and make a second Vietnam of Venezuela,” he said. Russia, he added, is “talking to Maduro in order to ease tensions inside the country and abroad. But we can’t command him.”

According to a person familiar with Guaido’s thinking, the National Assembly leader’s priority is to secure a significant humanitarian package to win over mid- and lower-ranking military members. As for the government, his stance is there is nothing to talk about except the terms of Maduro’s exit; anything else would allow Maduro to gain time to regroup, the person said.

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan called Maduro last month to assure him of his support, addressing him as “my brother!” The destination for tons of Venezuelan gold, Turkey has offered to take in Maduro, although only as a last recourse, according to a person familiar with the discussions. Any decision would be taken by Erdogan directly, and right now the priority is on backing him at home, a senior Turkish official said.

The Vatican may also have a role to play in organizing some kind of exit for Maduro, another person said. Guaido urged Pope Francis in an interview with Italy’s Sky TG24 broadcast last week to act as a mediator in Venezuela.

If Maduro turned to Russia, President Vladimir Putin would give him refuge, said Andrey Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council, a research organization set up by the Kremlin. “It’s not in our rules to give up our own — and he is still one of ours,” he said.

Russia, however, thinks Maduro can survive the crisis, according to Kortunov. “I believe Maduro has boltholes closer than Russia,” he said. “But this is still premature. So far, the regime has shown some resilience.”

(By Esteban Duarte, Eric Martin and Ilya Arkhipov)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments