Lithium battery dreams get a rude awakening in South America

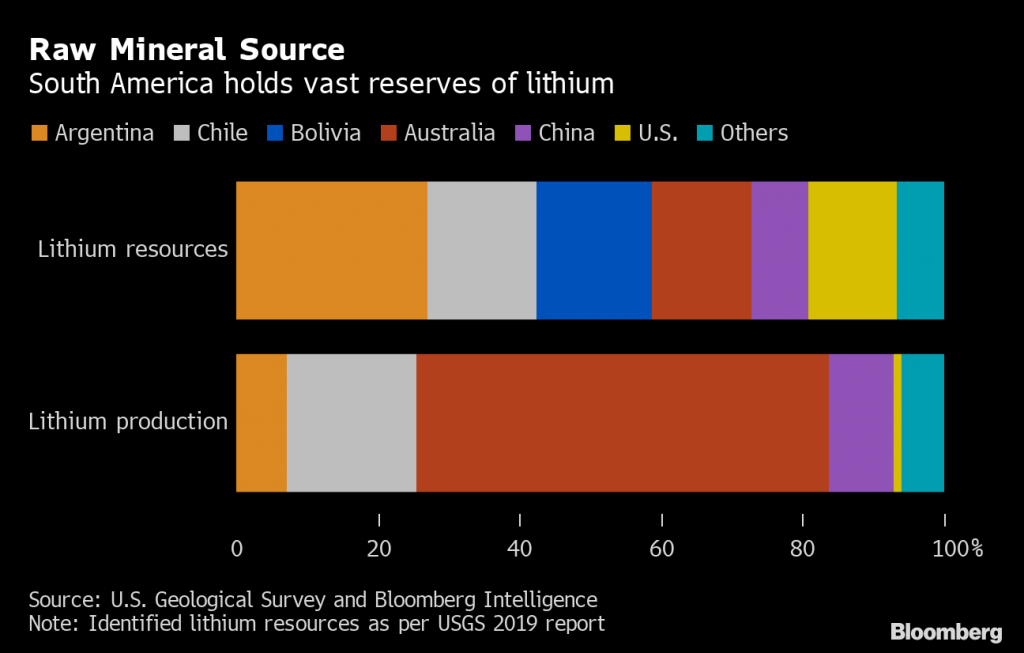

South America controls about 70% of the world’s reserves of lithium, the metal used in rechargeable batteries for mobile phones and electric vehicles, but none of the infrastructure needed to put it to work.

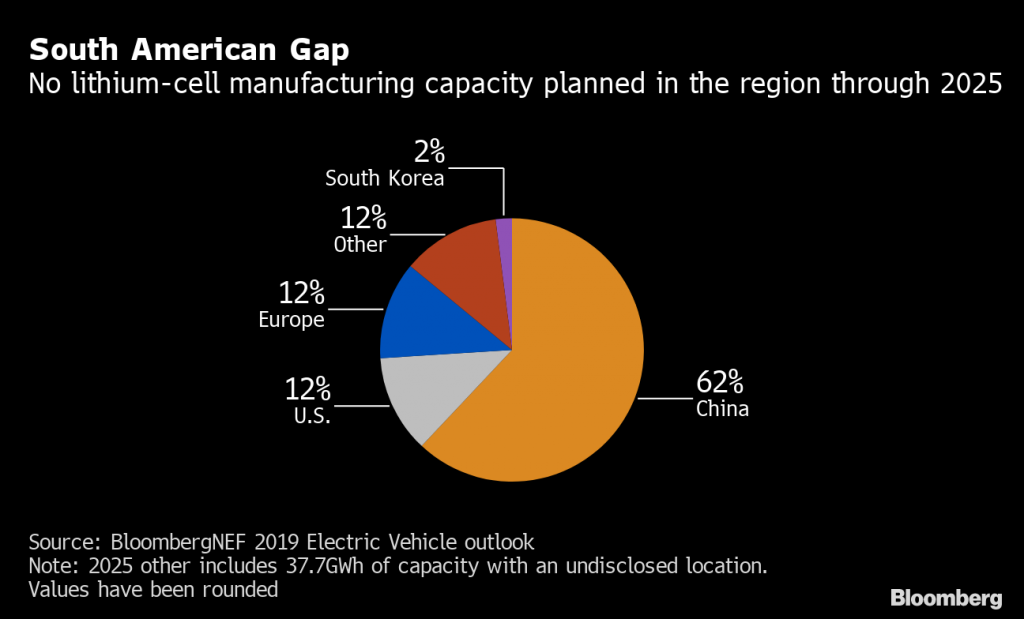

Lithium refining and battery-assembling facilities could help kick start industries in economies that are largely dependent on commodities for revenue, putting them at risk from sharp price swings. But so far, public and private initiatives in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Chile have failed to deliver even a single lithium cell factory. And none are set to be built through 2025.

Chile, the world’s second-largest lithium producer behind Australia, offers perhaps the best example of an effort gone off track. A $285 million lithium-cell project by two Korea-based companies was canceled in June when plunging lithium prices undercut government incentives on the metal. Meanwhile, a local company that assembles batteries using components from abroad is struggling to get lithium cells to support their sales in Chile.

“The size of the opportunity is huge,” said James Ellis, the head of Latin America research at BloombergNEF. “It makes sense to try to move up the value chain. But when you look at what’s planned globally, there are no battery manufacturing assets in Latin America.”

Other countries in the region face their own challenges. Here’s a breakdown:

Argentina

The third-largest lithium producer also saw a state-sponsored initiative stall.

Last year, Italy’s Seri Industrial SpA formed a joint venture with state-owned JEMSE, or more formally the Jujuy Energy and Mining State Society. The plan was to build a plant to make lithium cathodes and cells, and assemble battery parts, using raw lithium mined in Argentina’s Jujuy province.

But Argentina’s economic crisis and the possibility that Peronist candidate Alberto Fernandez could win the upcoming presidential elections has, in the words of JEMSE President Carlos Oehler, “cooled all investment projects in Argentina, including building a battery factory.”

The land and permits are ready, Oehler said, “and we were starting to look for financing, but the project is frozen now.”

Brazil

In Latin America’s biggest economy, former Tesla Inc. executive Marco Krapels and former SunEdison Inc. executive Peter Conklin founded MicroPower-Comerc with the initial goal of providing rechargeable batteries to commercial and industrial facilities. But Brazil offers almost no government subsidies for renewable energy, and import taxes add about 65% to the cost of the batteries.

That’s driven the company, which is backed by Siemens AG, to consider buying components abroad and assembling them in Brazil as a way to lower their costs.

While the nation’s market for big batteries barely exists, Krapels sees opportunity in a place with an occasionally unstable power grid and a robust market for wind and solar. “This is not for the faint of heart,” he said in an interview last month. “But I think there’s an advantage on being the first to move into a market.”

Bolivia

Bolivia hasn’t managed to produce significant volumes of lithium or lithium products. But it is home to the world’s largest salt flat, covering 6,437 kilometers (4,000 square miles), and holding more than 15% of the world’s unmined lithium resources.

A pilot plant run by state-owned Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos, or YLB, produced close to 250 tons of lithium carbonate in 2018, and the country’s goal is to generate 150,000 tons within five years, partnered with German and Chinese companies. If it succeeds, Bolivia would become one of the top-producing nations.

Last month, Industrias Quantum Motors SA began sales of the first car ever built in the country, an electric vehicle that answered President Evo Morales’s once-cited wish to see a lithium-powered car “made in Bolivia.”

The problem? Eager buyers aren’t allowed to drive the cars on Bolivia highways until the government can change some existing regulations.

Chile

The lithium producer tried to encourage battery companies to build factories in the country by forcing miners to sell lithium at a discount. That attracted interest from giants including Samsung SDI Co. and Posco in 2017, when lithium prices were at historic highs.

But since then, prices have fallen by a third, and earlier this year the companies abandoned their plans to build.

Even those embarked in less ambitious initiatives are facing hurdles. In Chile’s south, Andesvolt currently imports battery components from abroad and assembles them in the southern city of Valdivia. It supplies lithium-ion batteries for electricity companies including Enel Americas SA, which installs them as back-up power in industrial, commercial and residential facilities across the country.

Andesvolt expects to produce 1,000 kilowatt-hour this year, up from 200 kilowatt-hour last year. But he is finding it so difficult to import lithium cells that he is considering building South America’s first lithium-cell factory. Dealing with the hiccups of importing the cells from China is just too much, founder and Chief Executive Officer David Ulloa said.

Lithium cells are highly volatile and can explode if not handled properly, which means shipping companies are often reluctant to transport them. Even when they do, there’s no guarantee the cargo will arrive on time — or arrive at all.

“We’ve seen it all,” Ulloa said in an interview. “Once a Chinese supplier didn’t do any of the paperwork needed for Chilean customs and later offered to disguise the cargo as shoes — we’re a serious company, we couldn’t accept that and we lost that shipment.”

(By Laura Millan Lombrana)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments