Lead’s viral resistance carries a lesson for other metals

(The opinions expressed here are those of Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

The demand shock rippling around the world as the new coronavirus spreads has upended the industrial metals complex.

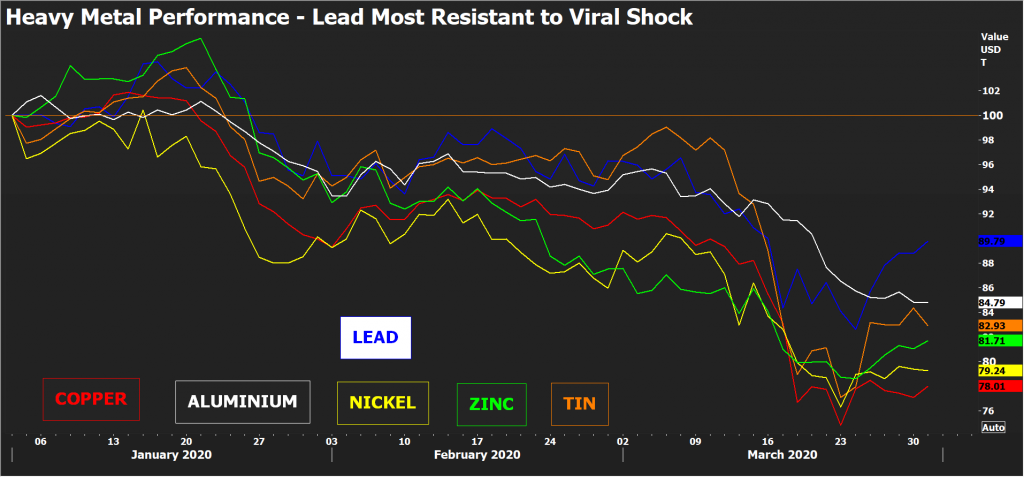

All the base metals traded on the London Metal Exchange (LME) are trading below their year-start levels.

However, one metal is proving remarkably resistant.

Lead, trading in London at $1,725 per tonne, is down by just 10.1% so far this year.

Zinc, the second best performer, has fallen by 15%. Copper, the LME’s bellwether contract and investors’ favourite metallic play, has slumped by 22%.

Lead’s apparent resistance to the viral chill on manufacturing activity is counter-intuitive, since it is most exposed to the automotive sector

Lead’s apparent resistance to the viral chill on manufacturing activity is counter-intuitive, since it is most exposed to the automotive sector, which has globally come to an almost complete standstill.

But the heavy metal’s resilience has already been seen in China, the country that is ahead of the coronavirus curve and which offers a template for how things might pan out everywhere else.

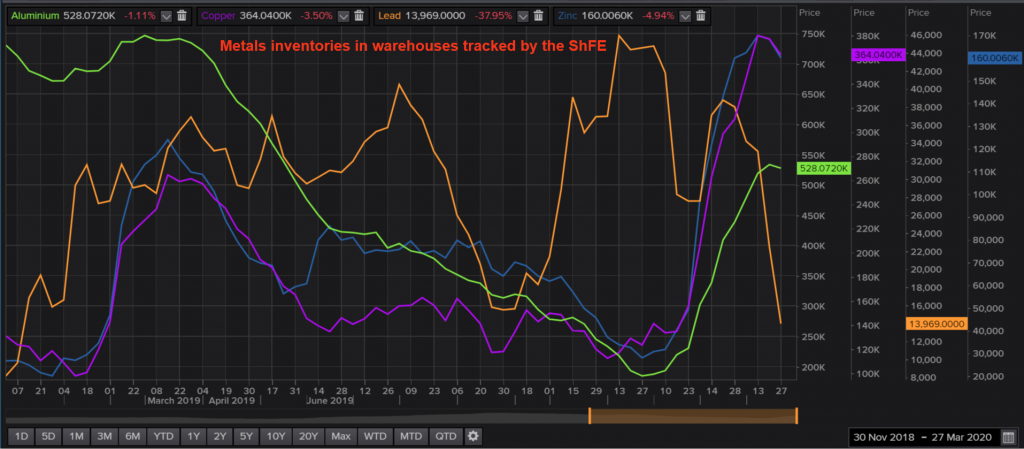

While stocks of aluminium and copper have piled up in Shanghai Futures Exchange warehouses as demand collapses, lead inventories have fallen by 30,600 tonnes to a 15-month low of 13,969 tonnes.

Lead’s differentiator is the speed of the supply shock that is running in tandem with the shock to demand. There may be a lesson here for other industrial metal production sectors.

Crisis management past

Past periods of collapsing metals demand and prices, such as seen during the global financial crisis or the cyclical trough of 2015-2016, have conformed to a classic commodity template.

A supply response lags the price signal because no producer wants to voluntarily relinquish market share at the expense of rivals.

The instinct is to hunker down, suck up the financial pain and wait for weaker operators to close.

This process plays out first at the mine stage of the production chain. Bigger companies know they have the balance sheet strength to continue operating, which means that a supply response to lower prices is an attritional process, comprising lots of smaller operators one by one throwing in the towel.

Once that process gathers momentum, it eventually feeds through to the refined metal stage of the production stream with smelters lowering operating rates in response to a tightening of raw materials availability.

The whole rebalancing process can take time. Sometimes a lot of time.

The one exception to this metallic rule of thumb is aluminium, where the smelter segment is more responsive to lower prices than the raw materials base. That’s because bauxite mining isn’t hard-rock mining at all but rather much cheaper open-pit quarrying.

But aluminium producers have historically been the slowest to react to low price signals because turning off smelters is itself expensive. The result of the 2008-2009 downturn in demand was a prolonged stand-off between operators and a massive build in unsold inventory.

Crisis management present

The collective supply response to the coronavirus demand shock is playing out faster.

This is because of multiple lockdowns on mining activity in major producer countries such as Peru and Chile, both of which have instituted emergency quarantine measures.

But that doesn’t automatically mean that smelters shut up shop. Indeed, Chinese zinc and aluminium metal producers actually lifted their production in the first couple of months of 2020, pumping metal into a demand void. Hence the rapid build in Shanghai inventories of both metals.

Lead’s outlier status is partly down to one specific company. Hindustan Zinc is a fully integrated mine-to-smelter producer of both zinc and lead and it has halted all operations to comply with India’s nationwide lockdown.

The company produced around 185,000 tonnes of refined lead last year. Relative to global refined production of 11.75 million tonnes, that doesn’t sound like much.

But this is where lead’s unique production profile is relevant.

The International Lead and Zinc Study Group estimates that primary metal production, meaning lead produced from mined concentrates, represented only 36.5% of global output last year.

The loss of production in India, therefore, represents over 4% of global output on an annualised basis.

The rest of the world’s lead supply last year came from secondary, or scrap, feed, which in lead’s case means spent automotive batteries.

It’s the hit to that part of the supply chain that explains lead’s super-fast supply response.

Freezing the supply chain

The battery recycling sector depends on geographically extended collection systems, which have been knocked out of action by lockdowns.

This is why China hasn’t accumulated excessive lead stocks over its lockdown period. Quarantine measures effectively froze the whole supply chain with lead recyclers having no choice but to cut production.

Demand for new batteries may have fallen off a cliff. But supply was being simultaneously constrained at the metals stage of the production chain.

Something similar seems to be playing out in other parts of the world.

France’s Recylex has mothballed both its recycling plants and its 140,000-tonne per year lead refinery in Germany until further notice.

It had no choice given the collapse in demand from the automotive sector and the simultaneous slowdown in used battery collection.

But, if replicated by other recyclers, the lead market will minimize the disconnect between supply and demand during this crisis. That in turn means no massive build in stocks left hanging over future prices.

The same scrap dynamic applies to other metals, all of which use recycled material as a production input, albeit to a lesser extent than lead.

Copper scrap, for example, has a proven track history of reacting much faster to price signals than the conventional mine-to-metal supply chain. Indeed, it is often the hidden market balancer during times of price stress.

Lead’s lesson for the rest of the industrial metals complex is that freezing the entire supply chain during an extraordinary demand shock leaves the entire market in better shape once demand comes back.

Lead producers have been forced to react by the metal’s unique production profile.

Copper, aluminium and nickel producers may not face the same imminent raw materials crunch but they might want to consider voluntary action to restrain metal output.

The novel coronavirus is rewriting the commodities rule-book. This might be the time to rewrite the supply response rules as well.

(Editing by Barbara Lewis)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments