In the land where coal is king, mine jobs outweigh climate fears

For Ann Taylor, the idea that Australia’s colossal coal industry should be tamed is risible.

Taylor is mayor of a council in Queensland state that already hosts 26 mines. She wants more added from the nearby Galilee Basin, a coal-rich area about the size of the U.K. that, if fully developed, could more than double Australia’s exports of the fuel.

“We’re absolutely pro-coal mining and proud of it—that’s why we’re here,” Taylor said in her office in Moranbah, a town of 8,000 people that owes its half-century existence to the industry. “There’s a lot of life left in coal.”

Coal is Australia’s second-largest income generator after iron ore, and many lawmakers welcome efforts to boost an industry that brings in A$60 billion ($42 billion) a year. None more so than Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who as the country’s treasurer two years ago brandished a lump of coal in parliament, taunting lawmakers from the opposition Labor party that they were scared of the fuel because they favored more cuts to carbon emissions.

Australia is the world’s biggest coal exporter, and the Galilee Basin will help decide whether it holds on to that status

As elections near on May 18, polls suggest that Labor leader Bill Shorten may now have the advantage over Morrison’s conservative government, with energy and the environment a key political dividing line. Yet there’s a limit to how far Shorten is willing to antagonize the coal industry. For even in the world’s driest inhabited continent, the imperatives of boosting revenue and economic growth are trumping concerns about the negative effects of man-made climate change.

Australia is the world’s biggest coal exporter, and the Galilee Basin will help decide whether it holds on to that status. Morrison’s government has been full-throated in its backing for Indian billionaire Gautam Adani’s plan to open up the Galilee with his Carmichael mine. Shorten has been less forthcoming. He is stuck between his party’s traditional support of the mining industry and lawmakers representing inner-city districts in Sydney and Melbourne who are against Carmichael on environmental grounds. Repeatedly pressed to clarify his stance during the campaign, the Labor leader remains ambivalent.

Bruce Currie is desperate for clues since whichever side prevails will affect his livelihood, perhaps permanently. A cattle farmer struggling to eke a living on the fringes of the Outback, Currie has seen his ranch stricken by drought that’s cut his herd from 1,500 head of cattle to just 70.

“We’re on the front line right here,” Currie said, surveying his dam that’s been reduced to a shallow, muddy pond. While he fears climate change, Currie said his immediate concern is that the Carmichael project less than 100 miles away could deplete and pollute water from the Great Artesian Basin, the world’s largest natural underground water resource. To Currie, bore water from the basin is now a matter of life or death.

“If the mine goes ahead, it will destroy us,” said Currie. “We’re going headlong into a potential disaster.”

The chief executive of Adani’s Australian mining division, Lucas Dow, rejects concerns that Carmichael will create any damage to Australia—or to the world. Work on the mine will proceed as soon as environmental conditions are met, he said.

After eight years and A$3 billion spent by the Indian company, what was once planned to be the world’s biggest coal mine with a capital cost of A$16 billion has been dramatically scaled down as financial backers retreated amid a concerted campaign by green activists.

“The prospect that we’re going to walk away now is a nonsense,” Dow said in an interview at the company’s Australian headquarters in Brisbane, Queensland state’s capital.

“People seem to have the view that if they shut our projects down, all the problems of the world would be solved,” said Dow. “The stark reality is you would actually exacerbate them. Coal is abundant worldwide so if Australia doesn’t supply it, somewhere else will, but it will be of a lesser quality.”

“People seem to have the view that if they shut our projects down, all the problems of the world would be solved”

Concern that the project could collapse spurred the conservative government to offer Adani A$1 billion to help fund a 120-mile rail link from the Galilee to Abbot Point, a deepwater coal port. While that plan was vetoed by the Queensland state administration, the company is proceeding with a modified proposal that may let other miners, including India’s GVK Group and Australian billionaire Gina Rinehart’s Alpha Coal project, to use Adani’s infrastructure.

Abbot Point has become a focal point for environmental protests as it’s on the doorstep of the Great Barrier Reef, the UNESCO world heritage site whose value to the country’s tourism industry has been calculated as A$56 billion.

At Airlie Beach, a tourist town some 60 miles down the coast, Tony Fontes has seen changes to the reef’s condition in the four decades he’s worked as a dive operator and instructor since moving from California. Agricultural run-off, port dredging and damage from boat anchors have all taken their toll, yet he says the biggest threat is from climate change bleaching the spectacular coral white—a phenomenon that scientists say has intensified in recent years due to warming oceans. He fears worse is to come.

“Opening the Galilee Basin will create a huge carbon bomb in my own backyard,” Fontes said at the town’s marina. “It would be great if Australia could vote an anti-coal government in and set a standard for other countries like India and Canada.”

That wish looks to be in vain. The support of Morrison’s coalition for the industry is locked in; indeed, it argues that Australia has a moral obligation to export more coal to countries like India so they can raise living standards through better access to reliable electricity. And while Labor has voiced concern about Adani’s project, it still officially backs the mine.

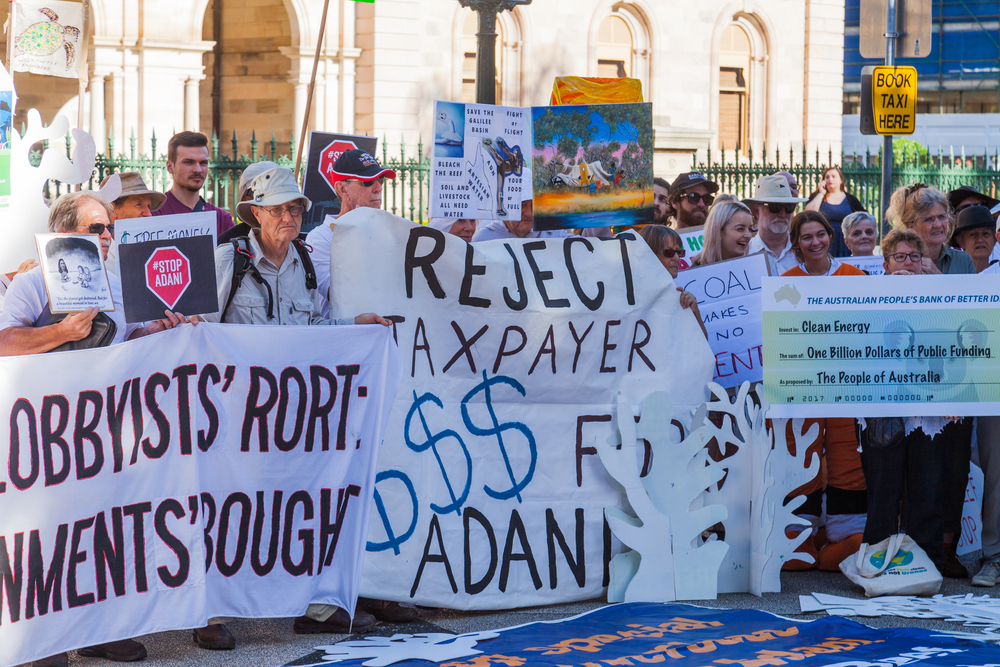

That could mean the fight against Adani and other future coal projects in Australia is left to increasingly frustrated environmentalists. During the election campaign, a convoy of protesters rallied against the Carmichael project, drawing thousands of supporters in the major cities before heading to the proposed mine site.

Anti-Adani protesters won’t find much of a welcome in Clermont, the closest settlement to Carmichael. Motel owner Paul Wilkes said protesters should they stay away from his three-pub, 2,000-people town. “I won’t sell them a room,” said Wilkes, 53.

As he sipped a morning coffee, a steady stream of mainly male workers in yellow fluorescent vests left their air-conditioned motel rooms and headed into the 38-degree Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit) heat to work in the region’s mines. “No-one’s against coal here,” Wilkes said.

(By Jason Scott)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments