India’s plans to double coal production ignore climate threat

As climate diplomats at COP28 in Dubai debated an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels last December, India was facing another energy conundrum: It needed to build more power capacity, fast.

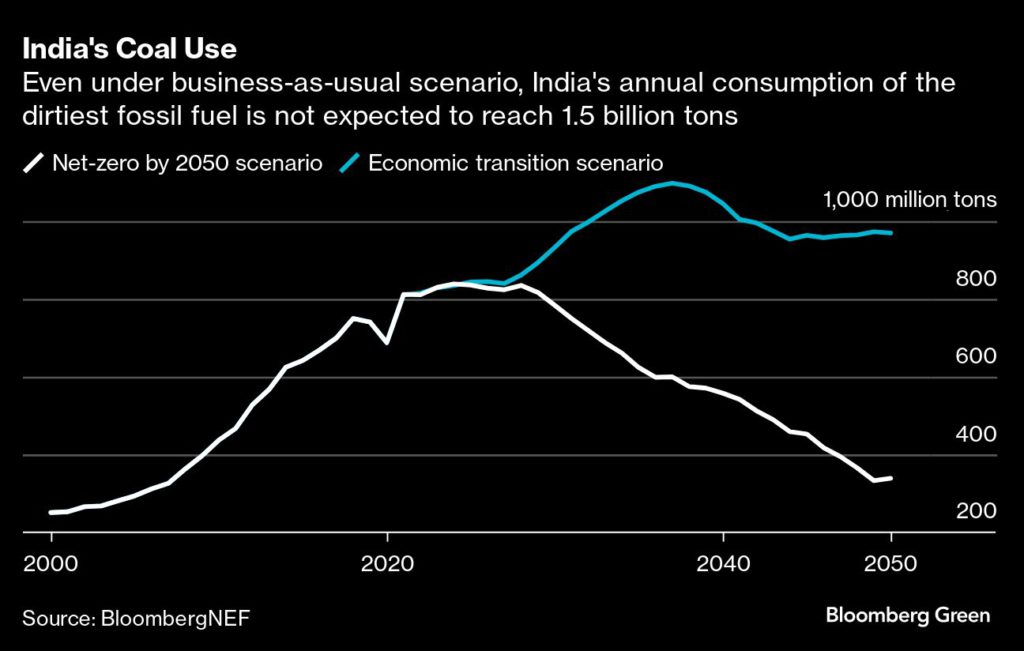

“To meet growing demand,” the Indian government said on Dec. 11 it expects to roughly double coal production, reaching 1.5 billion tons by 2030. Later, the power minister Raj Kumar Singh set out plans on Dec. 22 to add 88 gigawatts of thermal power plants by 2032. The vast majority of which will burn coal.

The move to invest more in the world’s dirtiest fuel – one of the biggest contributors to global warming – may seem counterintuitive for the South Asian country, which is highly vulnerable to climate impacts. Yet, as the country heads into elections during April and May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is keen to avoid any risks of power shortages. Along with record heat waves India has seen big spikes in peak demand for electricity over two successive years.

“India’s policy is to build everything. Push for renewables, but also push for coal and other fossil fuels,” said Sandeep Pai, director of the climate-focused organization Swaniti Global. “The justification is an increase in power demand.”

When it comes to renewable energy, however, India is failing to build enough to meet its ambitious goal of 500 gigawatts of clean-energy capacity by 2030. The rates at which solar and wind power was installed over the past few years is about a third of what’s needed, according to BloombergNEF.

There is a combination of factors affecting the renewables roll out. The top reasons, says Rohit Gadre of BNEF, are the misaligned incentives of state-owned electricity retailers, difficulty of acquiring the land necessary and lack of consistent policies at federal and state levels. As a result, even as the demand for power is rising, there’s not enough appetite among private investors to speed up renewable investments.

That is not to say things will be smooth for coal either, which is facing similar challenges in attracting new investment. “Solar and wind power plants can be built quickly, whereas coal power plants will take much longer and at higher costs,” said Vibhuti Garg, South Asia director for the non-profit Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Neither Pai nor Gadre expect India to reach the coal targets it has set. BNEF’s economic-transition scenario sees India’s coal use topping out at 1.1 billion tons before 2040.

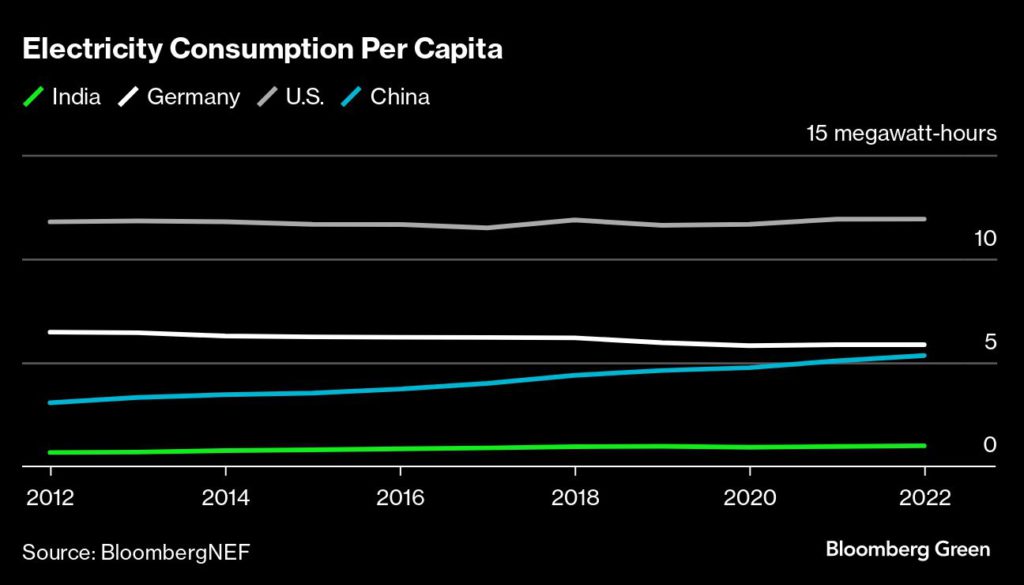

Ultimately, India needs investment in its energy infrastructure as the lower middle-income country seeks economic growth. Per capita electricity consumption for India is far below those of developed countries or even China. And India is still far from using up its fair-share of the global carbon budget.

India, as well as other big developing countries, also need more incentives to choose a greener path. Over the last three years, the Group of Seven nations have designed the Just Energy Transition Partnership to help South Africa, Vietnam and Indonesia to reduce coal use. Those deals have been messy and yet to show results.

While the world may have agreed to transition away from fossil fuels at COP28, it hasn’t found effective ways to help countries like India replace coal, environment minister Bhupendra Yadav suggested this week at a launch for the book titled Modi Energising A Green Future. That doesn’t have to be simply about rich countries handing out cash, he said at the event, but better policies, technology transfer and skills training are also needed.

Pai echoed this view. “The world needs to offer something to India to not carbonize,” he said. “The main challenge is the world really doesn’t offer much to India or to any developing country.”

(By Akshat Rathi)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments