Home: Guinea coup adds bauxite to aluminum’s supply concerns

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Aluminum extended its covid-19 recovery rally to hit a fresh 10-year high of $2,782 per tonne on Monday.

The trigger for the latest upswing was news of the military coup at the weekend in Guinea, a major producer of bauxite, which is processed into alumina and then primary aluminum.

[Click here for interactive aluminum price chart]

The aluminum market doesn’t normally pay much heed to disruptions at the bauxite end of the supply chain. It is, after all, the most common metallic element, accounting for around 8% of the earth’s crust, and production losses have historically tended to be quickly compensated.

No one’s expecting this time to be different, even assuming the military coup leaders were willing to put at risk one of the country’s main foreign revenue sources.

However, the political upheaval in Guinea catches the aluminum raw materials chain at a vulnerable moment with alumina prices already surging higher due to refinery problems in Brazil and Jamaica.

It also adds more fuel to a new bull narrative in the aluminum market, which after years of oversupply is now facing the possibility of a significant and persistent shortfall.

Bauxite impact seen limited

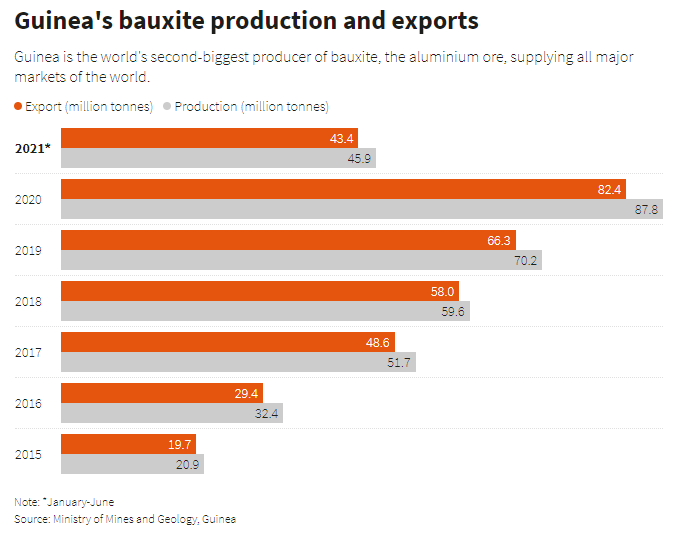

Guinea has over the last decade emerged as one of the world’s top bauxite producers.

The West African nation last year produced 78 million tonnes of bauxite, accounting for around 22% of global production, according to research house CRU.

With only one domestic alumina refinery, its prominence in the third-party market is starker and the country is a major supplier to refineries in Europe, North America and most of all China.

China’s bauxite imports have grown strongly in recent years due to “the deterioration in quantity and quality of domestic bauxite reserves”, according to CRU. Bauxite imports totalled 30 million tonnes in 2010. Last year they reached 112 million tonnes, of which 47% came from Guinea.

Fortunately for China’s import-dependent refineries, the direct impact of the coup in Conakry on the bauxite mining regions appears to be muted so far.

China’s refineries are also very well stocked, according to CRU, which estimates they are currently sitting on around 50 million tonnes of the stuff, representing almost half of annual imports.

They’ve benefited from a period of low pricing with the global market “crippled by surplus tonnages since 2019”, according to CRU. Ironically, that surplus has largely been down to fast-growing Guinean production.

A significant disruption of Guinean bauxite looks highly unlikely but it feeds into a narrative of constricted supply growth

All of which should help cushion the bauxite chain from any interruption of supply from Guinea even if it were to materialise.

That, however, hasn’t stopped the Chinese price for imported Guinean bauxite from hitting a near 18-month high this week.

Alumina stress

Nor has it stopped the price of intermediate product alumina spiking to a two-year high of $344 per tonne on the CME, although it has since slipped back to $322 on Tuesday.

The concern about bauxite supplies from Guinea has added to existing alumina supply-side woes after two production disruptions impacting the Atlantic sea-borne market.

Brazil’s Alumar refinery with a capacity of 3.5-million tonnes per year of alumina, reduced output by around one-third in July after damage to an unloading berth.

Then last month came news of a fire at the Jamalco refinery in Jamaica, a 1.4-million tonne facility owned by the government and Noble Group. The damage is still being assessed and the plant is out of action.

Trouble in the alumina market comes just as China’s own import appetite seems to be increasing, possibly reflecting the ripple effects of flooding at a Chinalco plant in Henan province in July.

Alumina imports surged to 527,000 tonnes in July, the highest monthly tally since December 2015.

The world’s bauxite-alumina supply chain is highly globalised and, as shown by events around the US sanctions on Rusal in 2018, surprisingly sensitive to unexpected kinks in that chain.

Supply chain sensitivity

The price spillover from alumina to aluminum markets also tells you how sensitive the latter has become to any hint of supply-chain disruption.

Aluminum has been on a rip-roaring rally since the covid-19 low of $1,455 per tonne in April last year.

LME three-month metal is currently trading at $2,760 per tonne, up 36% since the start of the year and the second-best performer after supply-starved tin.

Underpinning the rally has been a collective re-think about China, the world’s largest producer accounting for around 57% of global production.

This year has seen a growing number of smelters ordered to reduce output as provinces try and hit energy efficiency targets, China’s key policy tool to achieve peak emissions by 2030.

This is capping the country’s output to the point it is now importing significant amounts of primary metal to feed its domestic products sector.

China, lest it be forgotten, was until recently being blamed for building too much aluminum smelter capacity, producing too much metal and exporting too much in the form of products.

Indeed, the country’s seemingly endless ability to roll out more smelting capacity into any sign of price strength was the single most important dampener on the price action in the last decade.

Fast forward to 2021, however, and it’s becoming clear that the Chinese aluminum juggernaut is running out of road as Xi Jinping’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060 collides with a sector that is still overwhelmingly dependent on coal-fired electricity.

This new dynamic is why aluminum is trading close to levels last seen in 2011.

It is also why the market is becoming more sensitive to supply disruption at any stage of the bauxite-alumina-metal processing chain.

A significant disruption of Guinean bauxite looks highly unlikely but it feeds into a narrative of constricted supply growth in which any outage takes on added significance to market balance.

Copper has historically been the LME metal most sensitive to production outages because it has rarely generated enough inventory cushion to mitigate unexpected supply disruption.

That was never a problem for aluminum, a metal characterized by too much, not too little, inventory for the last 10 years.

Things, however, may be changing, judging by the way it’s reacted to news of potential (underlined) disruption at Guinea’s bauxite mines.

(Editing by Susan Fenton)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments