Home: Higher Chinese imports herald coming copper scrap surge

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

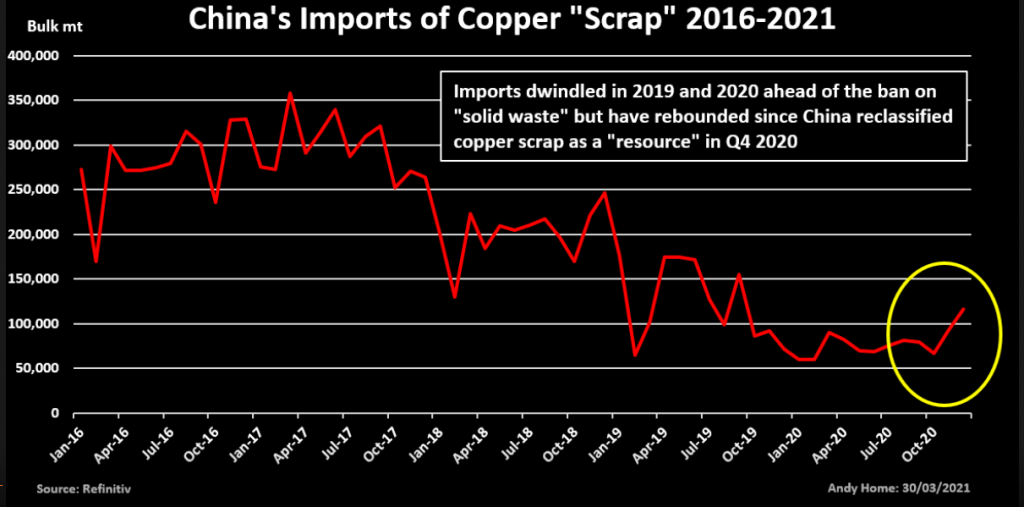

China’s imports of copper scrap surged over the first two months of 2021, jumping by 60% year-on-year to 191,720 tonnes.

A new import regime reclassifying scrap as a “resource” came into effect last November, removing high-grade copper recyclables from the list of “solid wastes” that are now banned.

China has historically been the world’s largest buyer of copper scrap but imports seemed in danger of disappearing altogether as the country’s customs department steadily tightened purity thresholds for metallic waste over 2018-2020.

The new customs codes should see import volumes recover, reducing the country’s need for copper in refined form this year.

Volumes will also recover because copper’s remarkable one-year rally will stimulate movement of the global scrap pool.

Just how much scrap flows down the supply chain in response to higher prices will determine the timing and degree of tightness in the global refined copper market.

Business as usual?

China’s copper scrap imports have averaged 103,000 bulk tonnes per month in the last three months, up from 76,000 tonnes in the three-month period before November’s customs code changes.

Delays to the new system – it was supposed to be rolled out in July last year – and ongoing teething problems are likely to restrain imports over the short term. So too will the combination of disruption to the shipping sector over the past year and the specific issues around container traffic to China.

That said, the new import tolerances are broader than many expected and China’s metals recycling body has just authorised another 26 foreign suppliers to supply copper scrap to the country.

That suggests that imports should continue accelerating over the course of this year, but the international scrap trade is unlikely to simply snap back to where it was before China started closing the door in 2018.

Recycled copper, whether fed directly into products or processed at a refinery, accounts for around 30% of global copper usage

Outright volumes won’t return to the previous peaks in the early part of the last decade, when China imported over four million tonnes of copper scrap each year.

Much of that volume was inflated by lower-grade material which cannot now enter the country even under the new customs codes.

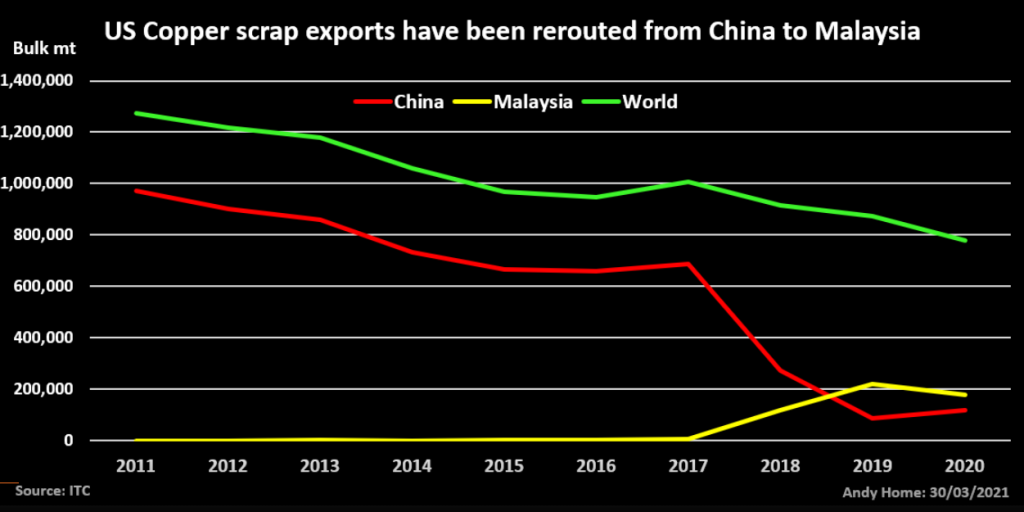

Moreover, trade flows have changed shape over the past couple of years with lower-grade scrap transiting through Malaysia, where it is sorted and upgraded to higher-quality material or copper ingots before onwards shipment to China.

Malaysia is now China’s largest supplier of copper scrap, accounting for 18% of total imports last year.

The United States, once the dominant supplier to China, accounted for just 11%. The country shipped more copper scrap to Malaysia than China last year.

China has in effect off-shored its lower-grade copper scrap business and the Malaysian upgrade hub looks to be here to stay.

Changing the balance

Copper scrap has been a key part of China’s supply picture for many years, which is why the country’s copper sector pushed back hard and ultimately successfully against a complete import ban.

When imports drop, it reduces both the amount of secondary refined production and the amount of “direct-melt” material used by product manufacturers, forcing buyers to turn to refined metal.

Several factors have combined to drive China’s red-hot imports of refined metal, which rose by 1.1 million tonnes to a record 4.7 million tonnes last year.

A strong post-coronavirus rebound in manufacturing activity, an associated restocking of the supply chain and strategic purchases by state agencies have all played a part.

So too has a shortage of scrap with total Chinese imports slumping by another 37% to 943,000 tonnes last year. Any offset from higher-purity levels was already largely spent in 2019 as all but the highest-content scrap was blocked.

Thus, the 550,000-tonne year-on-year decline in bulk volume imports translated into a significant supply shock for China’s copper industry.

Conversely, as copper scrap imports now pick up momentum, the displacement effect on the refined market should diminish.

Scrap wave

This relationship between scrap availability and the pull on refined copper is not just a Chinese but a global phenomenon.

Recycled copper, whether fed directly into products or processed at a refinery, accounts for around 30% of global copper usage each year.

The more lower-priced scrap is available, the less the amount of virgin metal needed to balance the market. A 1% rise in global scrap penetration is equivalent to around 300,000 tonnes of primary metal, according to Morgan Stanley (“Copper and Renewables”, March 23, 2021).

The single biggest driver of scrap availability is price. Higher prices incentivise the collection and processing of end-of-life scrap.

Global scrap volumes for refining into new metal jumped by 20% in 2006, a year when the copper price almost doubled, according to the International Copper Study Group. They continued growing over copper’s boom years and surged by another 25% between 2010 and 2012, when the price peaked out.

Copper’s price slide over the middle of the decade translated into a 10% decline in volumes by 2016, according to the group.

History suggests that a new scrap surge is imminent, given London Metal Exchange copper has more than doubled in price since last March’s COVID-19 low point of $4,371 per tonne.

For analysts such as Morgan Stanley this is a reason for caution about copper’s prospects over the course of 2021. The bank has a fourth-quarter forecast of $8,488 per tonne, below the current LME price of $8,780.

Citi, which is calling for a “copper supercycle”, is not convinced scrap availability can expand enough to fill its forecast 500,000-tonne supply deficit this year.

The bank looks at seven scenarios of potential scrap availability based on previous patterns and concludes that only one – a repeat of 2012 – would generate enough material to fill the gap. (“Supercycle sunrise – Part III”, March 23, 2021)

“We think this is a stretch and is not likely to occur as quickly as the market needs, given logistical constraints and the fact we find that there tends to be an eight-month lag between price strength and copper scrap export increases,” Citi argues.

The paucity of data on the scrap sector means that the numbers are inevitably ambiguous and so too is any calculation of the follow-through impact on the refined copper market.

But be in no doubt that scrap, one of the copper market’s most powerful balancing mechanisms, is about to have a revival. Just how strong will determine the copper market landscape over the coming months.

(Editing by Susan Fenton)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments