Freeport-McMoRan Inc. shares have fallen about 21 percent since they opened Monday, headed for their worst weekly performance in almost three years.

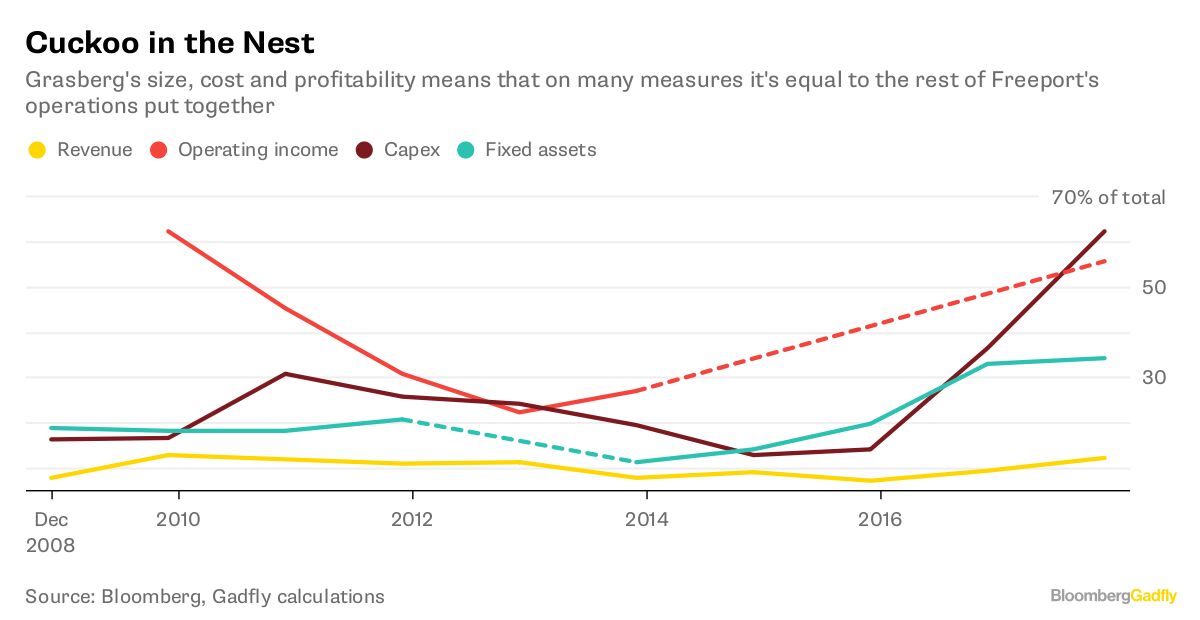

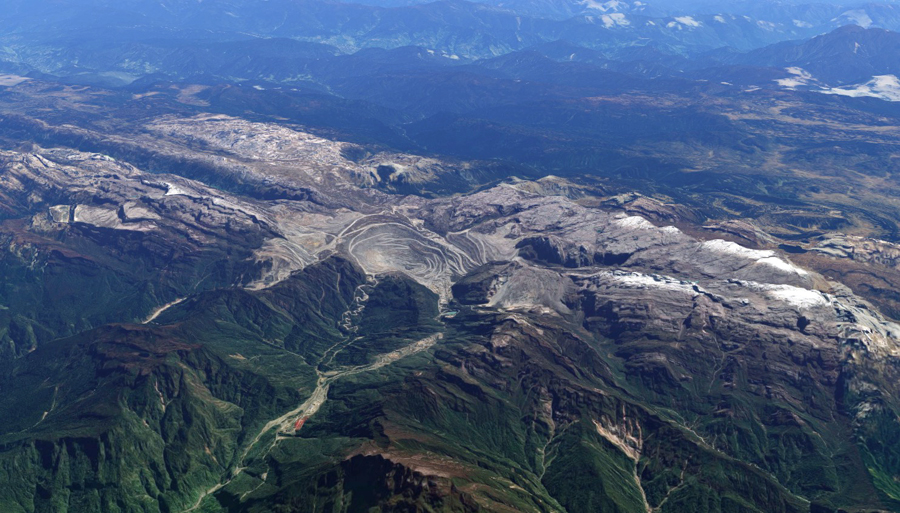

The reason is a further wrinkle in the Indonesian government’s attempt to lift its stake in the Grasberg mine on the island of New Guinea, one of the world’s biggest sources of copper and gold and among the most isolated and challenging pits on the planet.

Jakarta and Freeport President Richard Adkerson have been edging closer to an agreement for some time. After insisting he’d never let the government’s stake rise to more than 30 percent from its current 9.4 percent, Adkerson conceded last year that it could increase to 51 percent. A deal to convert Rio Tinto Group’s interest in the project into enough equity to give the government majority control – a neat way of getting around the trench warfare between Freeport and Jakarta – is intended to be finalized within months.

Now there’s a new hitch: A proposed change to the government’s environmental standards around the pit.

Under the current arrangement struck in 1994, several billion metric tons of mine waste that’s been dug from Grasberg over the past few decades is dumped straight into the Ajkwa river.

This tailings dump isn’t the sort of engineered, bulldozer-built berm pile seen near major mines elsewhere in the world. Instead, it’s a sort of inland delta formed from waste settling out of the stream naturally as it winds between man-made levees across the flood-plain. Much of the material drifts straight past and gets deposited at sea.

The new rules would lift the proportion of tailings that must be retained in the delta to 95 percent from the current 50 percent, Adkerson told an investor call this week. That level of recovery “just cannot be done,” he said: “You can’t revisit a system that was agreed to 20 years ago and has been operating effectively over 20 years with no unexpected environmental consequences.”

For all that Grasberg’s tailings system is inadequate, Adkerson is right to question whether the Indonesian government is motivated by environmental concerns. Jakarta wants state-owned PT Indonesia Asahan Aluminium, or Inalum, to get the lowest possible price for its Grasberg stake, and one way to do that is to sow so much political chaos that it can justify a discount valuation from sellers whose patience is wearing thin.

A proper solution to Grasberg’s substandard tailings system would be welcome – but also hugely costly, probably involving networks of slurry pipelines heading across the entire island and damaging its position as one of the world’s lowest-cost copper-mining operations. It’s hard to believe Jakarta would be happy to swallow its share of the expenses once it becomes majority owner.

The latest move demonstrates that, as Gadfly has argued, Jakarta holds all the best cards. Still, the pessimism that’s driven Freeport’s share price down so sharply this week might be overdone.

The worst-case scenario – a shutdown of the mine until the tailings situation can be resolved – isn’t really credible. Grasberg is one of the country’s biggest taxpayers, and with campaigning under way for a slew of provincial elections this year and President Joko Widodo up for re-election next year, the government will want that revenue at its disposal.

That timetable will mean it also wants this sorted out before voters go to the polls. With a resolution looking so close, it would seem self-defeating for the government to throw the process into turmoil for the sake of a billion dollars or so off the sale price.

After all, Freeport and Rio Tinto aren’t the only mining companies that Jakarta needs to be thinking about. If you pose as an unreliable partner to strike a hard bargain with one miner, the risk is that others end up thinking of you as an unreliable partner too, and reduce investments.

That appears to be happening. Foreign direct investment in Indonesian mining and quarrying, which averaged $2.2 billion a year during the second term of Widodo’s predecessor Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, has plummeted. During 2017, for the first time in records dating back to 2004, it went negative, with investors pulling out and losses on projects generating FDI of minus $1.2 billion.

Widodo’s government should take care. What does it profit a country if it gains a better price on one mine, and loses its mining industry as a result?

(Written by David Fickling)

Comments