Gold mine gangs tote AK-47s to outgun South African police

At 10 p.m. on the second Sunday in December, a criminal platoon armed with AK-47 and R6 assault rifles stormed one of the largest gold mines still operating on South Africa’s fabled Witwatersrand basin.

Moving with military precision, the 15 attackers took hostages and plundered the smelting plant at Gold Fields Ltd.’s South Deep mine. While failing to break into the main vault, the gang escaped three hours later with gold concentrate worth as much as $500,000.

Violent crime soared through a decade of kleptocracy and graft under South Africa’s former President Jacob Zuma. Gold mines offer soft targets for syndicates that previously specialized in cash-in-transit heists. Their foot-soldiers outgun a demoralized police force and pile woes on a gold industry in the final stages of a decades-long death spiral.

“Mining companies are being attacked by thugs and armed gangs and there is a lack of police response,” said Neal Froneman, chief executive officer of Sibanye Gold Ltd., which repelled an attack on its Cooke mine two weeks ago. “It eventually has a knock-on impact into society, it’s lawlessness, it’s anarchy.”

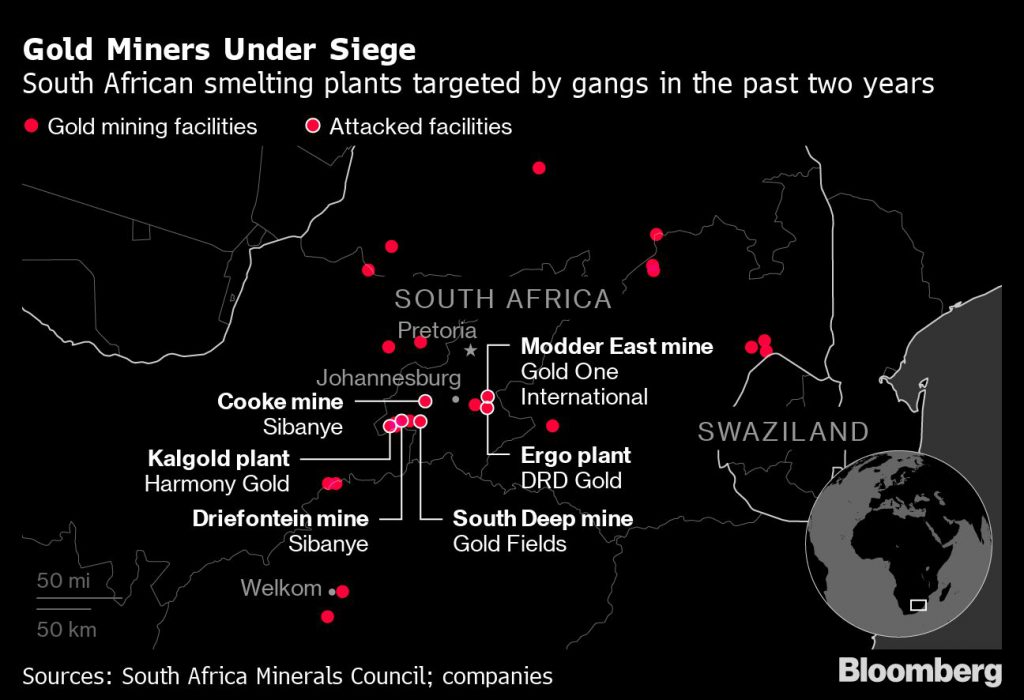

There were 19 attacks on gold facilities last year, almost double the number in 2018, according to South Africa’s Minerals Council. More than 100 kilograms (3,527 ounces) of gold was stolen in 2019 as bullion rose to a five-year high, although not all companies disclose their losses, said the council, which represents the nation’s largest miners.

The attacks are part of a wave of violent crime. Murders in South Africa climbed to the highest in a decade, with an average of more than 50 people killed each day. Violent robbery has surged and last year President Cyril Ramaphosa’s government deployed the army in Cape Town to quell gang-related killings.

Sibanye has strengthened its defenses after the nation’s biggest gold producer repelled several attacks last year

Ramaphosa has made combating crime a top priority since taking office in one of the world’s most unequal societies in 2018. While the violence is partly a legacy of apartheid rule that ended in 1994, his efforts have been hindered by the gutting of the National Prosecuting Authority and other law-enforcement agencies under his predecessor Zuma.

“The fundamental problem is police are not getting on top of organized violent crimes,” said Gareth Newham, who heads the justice and violence prevention program at the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria. “We are seeing a deterioration in our policing capacity.”

After meeting with gold mining companies in October, Minister of Police Bheki Cele is considering plans to set up a task force to tackle the violence, said Lirandzu Themba, a spokeswoman for the ministry.

When 50 robbers overwhelmed security at Gold One International Ltd.’s smelting plant in May, the police held back from engaging with the gang after they were fired on, according to Jon Hericourt, vice president of operations at the Chinese-owned miner. Since the gang made off with an unspecified quantity of gold, the police have only provided scant information on its investigations, he said.

Gold One has beefed up security and switched its focus from thwarting internal theft to combating all-out assaults. Still, Hericourt doubts that will be enough.

“It’s not a mining company’s job to take on gangs like this, it’s the government’s job,” he said.

Sibanye has also strengthened its defenses after the nation’s biggest gold producer repelled several attacks last year, said Head of Security Nash Lutchman. Combat training is now standard practice for guards, who wear bulletproof jackets and patrol in armored vehicles at night.

Still, their shotguns and 9-millimeter pistols can’t compete with the automatic weapons used by gangs. The raids take months to plan, with the gangsters coercing mine employees into providing inside knowledge, Lutchman said.

“It’s military precision in terms of planning and execution,” he said. “No smelting plant is going to have sufficient manpower and fire power to defend an onslaught from 20 or 30 attackers.”

In the final quarter of 2019, both Harmony Gold Mining Co Ltd. and DRDGold Ltd. suffered fatalities during assaults.

The attacks are putting additional pressure on South Africa’s 130-year-old gold industry, forcing companies to increase spending at often marginal mines that were already battling against incursions by illegal miners. That’s compounding the geological challenges of the world’s deepest mines, deterring investors already concerned by the country’s power supply crisis.

“It can potentially have a knock-on effect to potential investors as well because they are not going to invest in gold in South Africa because it’s too risky,” said Gold One’s Hericourt.

(By Felix Njini, with assistance from Samuel Dodge)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments