How a gold mine drama set this man on a path to lead Australia

For two weeks in 2006, Australia’s news cycle was dominated by the gripping and ultimately successful bid to rescue two men trapped in a collapsed gold mine. The real-life drama also unearthed an unlikely star — Bill Shorten, a union leader who’s now poised to become the nation’s prime minister.

“It was an incredible story and he made sure he was heavily involved in it,” says Barry Easther, who at the time was the mayor overseeing the remote Tasmanian town of Beaconsfield and watched Shorten position himself as the miners’ spokesman. While Easther believes his concern for the men was genuine, he said the unionist also “loved the media attention because he was very much building a profile.”

Shorten, 52, has rarely left the spotlight since. Thirteen years later, helped by a combination of political intuition, prodigious networking and hard work, he’s on the cusp of leading his left-leaning Labor party to victory in Saturday’s election and potentially ending Australia’s decade-long era of political chaos.

“Bill’s always been great at reaching out to people, making alliances and putting a team together that can get things done,” says Peter Cowling, who shared a flat with Shorten while they attended Melbourne’s Monash University in the 1980s. “The cliche comment about Bill used by his friends was there was no doubt he seemed destined to become a Labor prime minister.”

That goal is now within reach, and should he win power he faces the challenge of taking over an economy that appears to be running out of steam after nearly 28 consecutive years of growth. He will also need to navigate the intensifying trade war between the U.S., Australia’s most important ally, and China, its biggest trading partner.

Power broker

Shorten rose from working-class roots and became a union power-broker before winning his seat in parliament in 2007. While he quickly built a reputation within the party for crafting policy, his prominent role in removing two sitting Labor prime ministers means many voters still regard him as a back-room schemer.

Yet Shorten has earned respect for transforming the ramshackle party into a disciplined, united force since becoming its leader six years ago. His election platform has focused on stripping back tax incentives to redistribute wealth from older, comfortable Australians to a younger, poorer generation.

“This economy is more likely to grow sustainably when millions of Australian households are getting regular wage rises, getting support with cost of living, having a properly funded health-care system,” Shorten told an audience while on the campaign trail this month.

Shorten’s fixation on fairness was instilled in him by his parents. His father was a British immigrant working on Melbourne’s notoriously rough-edged wharves who organized union meetings, while his mother — described as his “biggest inspiration” — was a teacher who in later life became a barrister.

Although she shepherded Shorten into studying law at one of Melbourne’s most prestigious universities, he paid his own way through manual work, including cleaning up in a butcher’s shop. At the same time, he was using his nascent networking skills to lure eminent Labor figures such as prime ministers Bob Hawke and Paul Keating to speak to students.

‘Saving the world’

“Bill’s talent was to make student politics interesting and accessible to everyone,” says Cowling, who’s now the Australian head of Vestas Wind Systems A/S, the biggest maker of wind turbines. “His idea was you can have fun while saving the world.”

Shorten’s first full-time job was as a youth affairs adviser for the Victoria state Labor government. He then defended injured workers at a private law practice, and in 1994 began working for the Australian Workers’ Union. By 2001 he was leading the organization.

“Beaconsfield catapulted Shorten into the national spotlight and showed he was a potential Labor leader because his support of the working class looked genuine”

He was also mixing in more opulent circles, and was a friend of the late billionaire packaging mogul Richard Pratt.

Shorten met his first wife Deborah Beale, whose father was a lawmaker for Labor’s conservative rivals, while studying a Master of Business Administration degree; he’s now married to Chloe Shorten, the daughter of former governor general Quentin Bryce.

Known as a talented union recruiter, Shorten was willing to compromise with employers’ pleas for higher productivity from workers as long as his demands for better conditions were met.

Still, the power of Australia’s unions was withering. Shorten seized his chance to put a positive spin on the movement during the Beaconsfield mine collapse, which gave him a podium to rally for worker safety improvements — and boost his own profile.

“Beaconsfield catapulted Shorten into the national spotlight and showed he was a potential Labor leader because his support of the working class looked genuine,” says Andrew Hughes, a lecturer in political branding at Canberra’s Australian National University. “It showed a great political instinct and a willingness to create his own luck.”

Shadowy force

After Beaconsfield, the time was ripe for Shorten to launch his political career and he entered parliament in 2007, riding the wave as Labor returned to government for the first time in 11 years under Kevin Rudd.

Labor’s six years in office were a mixed bag for Shorten. Within the party he earned a reputation as a hard-working policy reformer, re-crafting the nation’s mandatory pensions program and helping to create a managed market for disability services as he managed portfolios including employment, financial services and education.

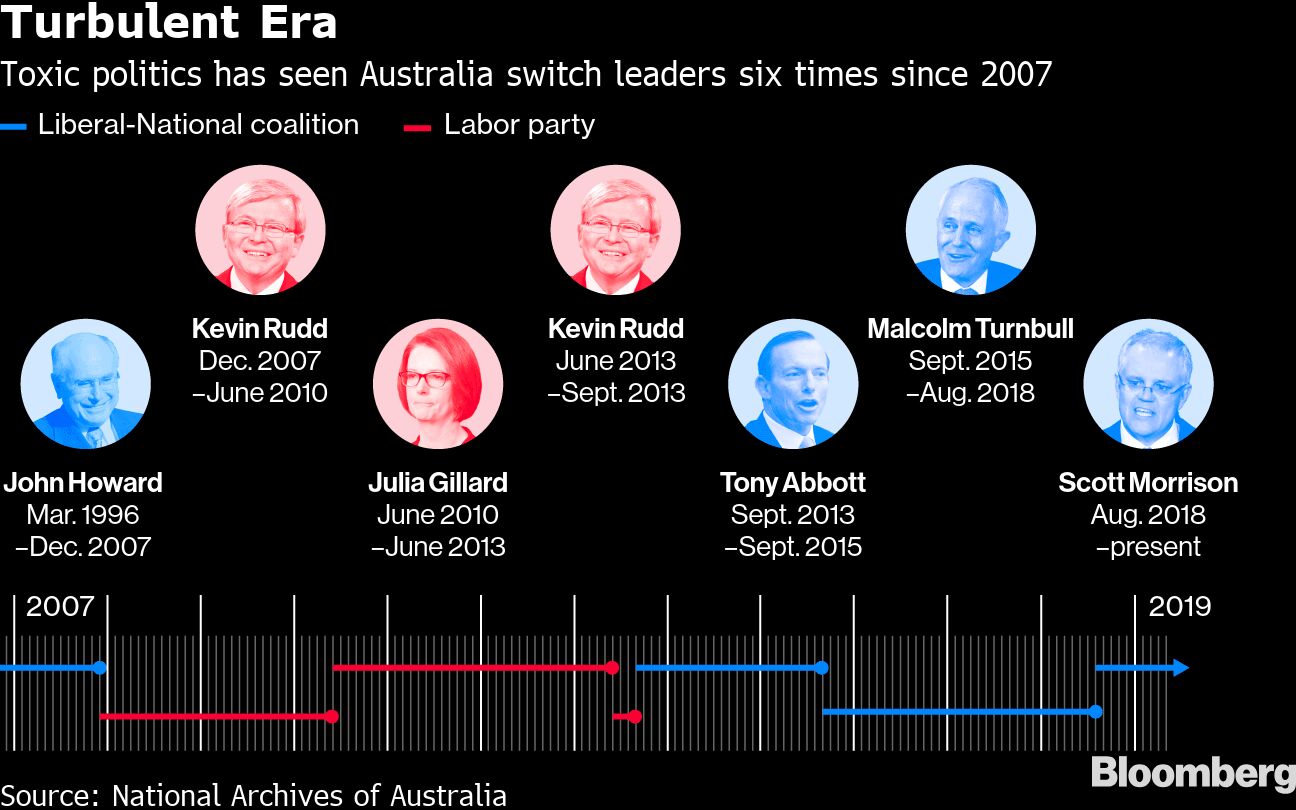

Yet he was also seen as a shadowy driving force behind internal Labor party votes that saw two prime ministers removed by their own lawmakers.

At the time Rudd was abruptly removed as leader by Labor in 2010, Shorten was filmed in a Canberra restaurant phoning colleagues to ensure their support for Julia Gillard. He was labeled by media as the “Faceless Man,” a moniker that resurfaced three years later when Rudd enacted his revenge on Gillard with Shorten’s support.

He seemed an unlikely choice when the party turned to him to lead it back from the wilderness after a thumping election defeat in 2013 that was partly blamed on Labor disunity.

“When he became leader, he caught everyone by surprise by his willingness to consult and with his calmness,” says Stephen Conroy, an old friend of Shorten and Labor colleague who served for three years as his deputy Senate leader. “I used to ask him if he’d been taking lessons in Zen Buddhism.”

Policy agenda

That discipline was tested in 2015 when Shorten had to testify at a probe into union corruption ordered by the Liberal-National coalition government.

Despite Shorten’s credibility as a witness being questioned in the investigation, which unveiled payments under his watch to the union by companies for training, advertising, and social functions, his leadership survived.

Shorten, whose office didn’t respond to a request for an interview, set to work crafting a solid policy agenda, including tougher action on climate change and boosting spending on taxpayer-funded schools and hospitals. He outlasted two prime ministers in Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull as the conservative coalition suffered its own bout of infighting.

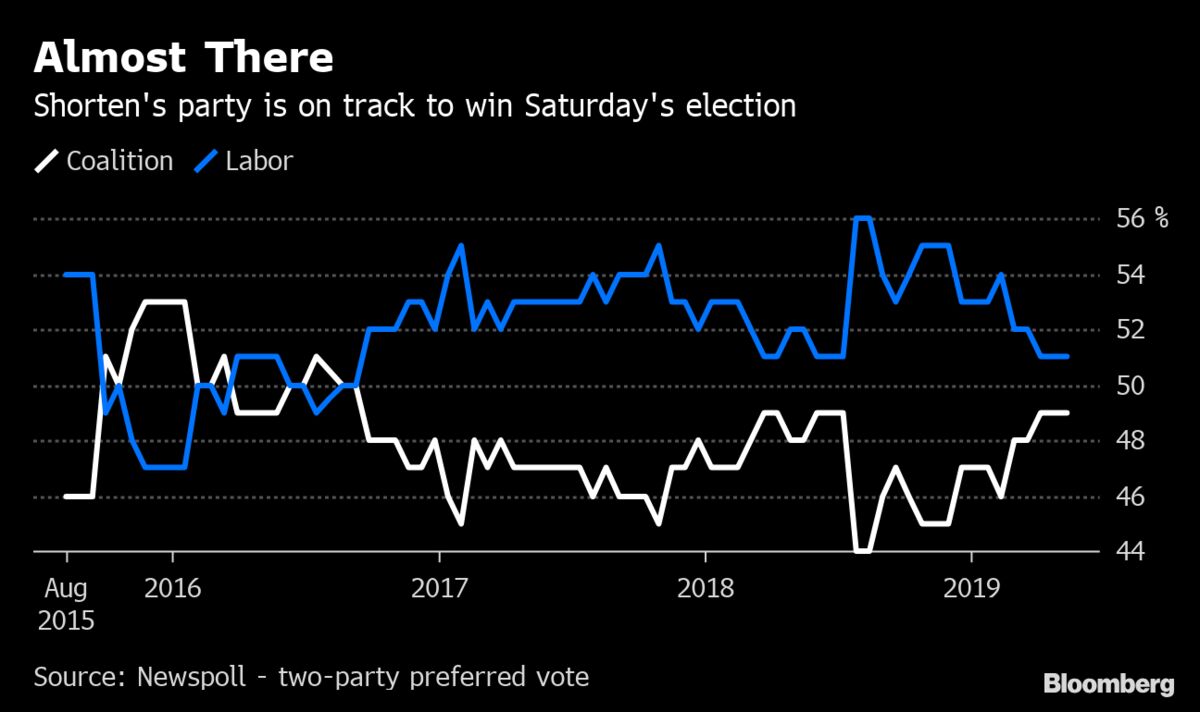

In 2016, he came within a couple of seats of a shock election win. This time, he’s even closer to the top prize. Despite Shorten being less popular with voters than Prime Minister Scott Morrison, Labor has consistently led the conservatives, who are campaigning on broad tax cuts and national security.

Brant Webb, one of the two workers rescued from the Beaconsfield mine, thinks he’s prime minister material. He’s become a friend of Shorten, who calls him every year on the anniversary of the collapse to help manage his grief, as the disaster also claimed the life of a colleague.

“Bill looked after my family and friends when there was every chance I wasn’t going to make it out alive — I can’t thank him enough,” says Webb, 50, between serving customers at the Tasmanian hotel where he now works. “He listens to the workers and will help them, but he also understands the business community. He’ll change Australia for the better.”

(By Jason Scott)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments