In just four months, Glencore Plc chief Ivan Glasenberg has lost two of his closest business allies as President Donald Trump’s aggressive foreign policy hits home, forcing him to cut ties with billionaires Oleg Deripaska and Dan Gertler.

The U.S. actions demonstrate the rising risk from international sanctions for companies like Glencore, which has built a global business by cutting deals with powerful people, and leaves the trader without its key men in two major markets.

Glasenberg has quit the board of Deripaska’s United Co. Rusal, and Glencore abandoned plans to swap its stake in the Russian company with another of the oligarch’s businesses, En+ Group Plc. Deripaska is the second recent Glencore associate to face U.S. sanctions. Gertler, the Swiss trader’s former partner in the Democratic Republic of Congo, was singled out by America in December over allegations of corruption.

Watch out

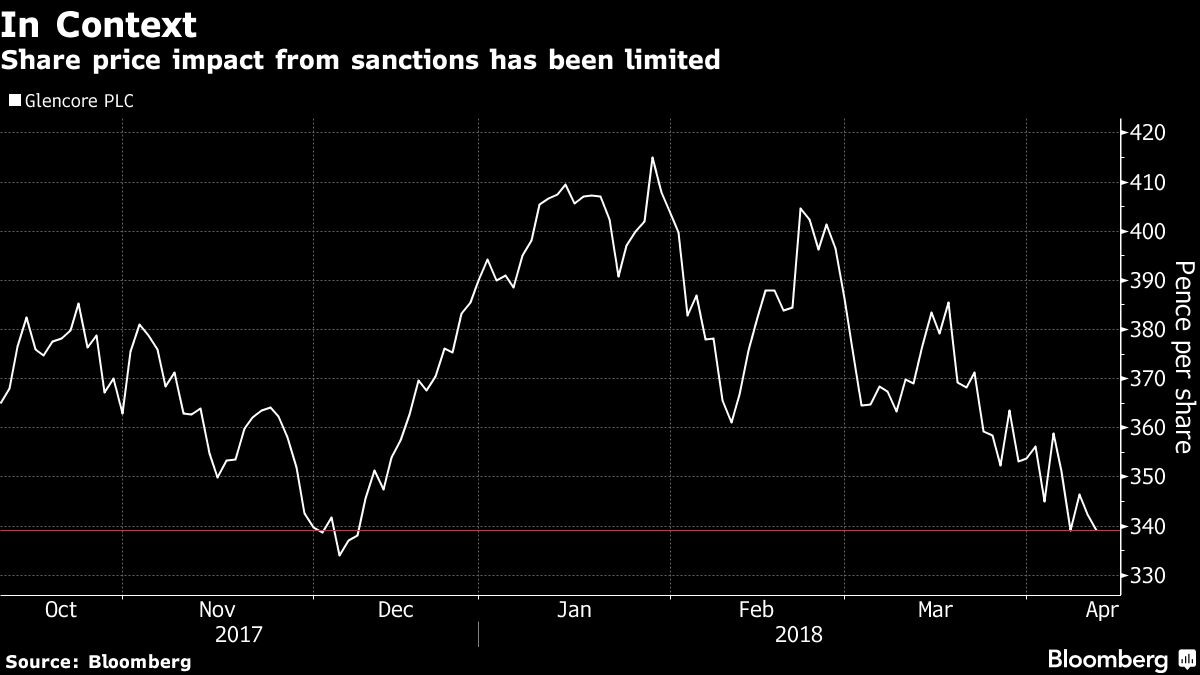

Analysts see limited damage to Glencore’s bottom line from last week’s raft of Russian sanctions — the company’s shares are still off the low earlier this week — but the long-term implications for the trader and the commodity industry could be more significant.

“The message to companies is you have to watch out who you are doing business with,” said former U.S. Ambassador Daniel Fried, who coordinated the State Department’s sanctions policy under the administration of Barack Obama.

“Business conducted with the world’s bad guys is going to have a higher risk premium.”

Glencore, which trades in 100-odd commodities in more than 90 countries, has partly built its business by dealing with people and places that others avoided. While many of its commodity competitors also operate in high-risk jurisdictions, few have a footprint as large as Glencore. Alongside Congo and Russia it mines Kazakh gold and zinc, drills for oil in Chad, and trades petroleum products in Libya. The Swiss commodity giant declined to comment.

The trader had already distanced itself from Gertler before sanctions hit, buying out his stakes in its two Congo mines 10 months earlier in a near $1 billion deal. Yet, it still faces questions on how to manage royalties it’s contracted to pay the Israeli businessman. With respect to Deripaska, Glencore has an 8.75 percent stake in Rusal, which has already lost more than half its value, and a multi billion-dollar deal to buy its metal.

Trouble shooter

More importantly, U.S. action has now forced Glasenberg to review two relationships he spent a decade cultivating and that gave his firm privileged access to decision makers.

In Congo, where Gertler had aided most of Glencore’s engagement with the government, the company now needs to navigate a series of complicated roadblocks without its trusted trouble-shooter.

In Russia, Glencore has other links to the Kremlin and relationships in the local oil and agriculture industries that have yet to be targeted by the U.S. Last year, Glasenberg was even awarded Russia’s Order of Friendship medal by President Vladimir Putin. Deripaska, a Glencore partner since at least 2007, was one of the company’s most important allies.

High risk

Barclays Plc and Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. analysts are among those arguing the financial fallout from U.S. sanctions will be limited. Yet, there’s no doubt that Trump’s aggressive foreign policy adds uncertainty.

“Russia has always been a high risk, high gain business environment,” said Fried from Washington. “They took advantage of the high gain, now they are learning about the high risk.”

Glencore has a history of taking such risks in its stride. Founder Marc Rich was indicted in 1983 for trading oil with sanctioned Iran and spent years on the FBI’s most wanted listed.

Three decades later, Glasenberg won oil industry admiration with a bold deal to buy an $11 billion stake in Russia’s biggest oil company, Rosneft PJSC, in a transaction that the U.S. reviewed for potential sanctions violations but didn’t block.

What’s different today is that America has refined its financial arsenal and then put it in the hands of a president who favors gut instinct over chess-like maneuvering. The Obama-era 2016 Global Magnitsky Act, which significantly expanded the reach and flexibility of sanctions, allows the U.S. to punish individuals accused of corruption or human rights violations anywhere in the world, without the need to first establish a specific program to target the behavior.

While the prior administration focused on a longer-term policy agenda, Trump seeks to punish those he views as wrongdoers, according to Maximilian Hess, a senior political risk analyst at AKE International.

Gertler, along with 14 others including including a Myanmar general, a former Gambian president and an organized crime boss from Uzbekistan, was sanctioned in December under the Act.

Glencore’s success has been based in part on operating in places “where others are uncomfortable,” said Hess. With changes in the U.S., “their current model is facing serious challenges.”

(Written by Tom Wilson and Thomas Biesheuvel)

Comments