New year, new trade deal.

The Phase 1 agreement signed by the United States and China may raise as many questions as it answers, but it does at least dispel some of the global trade uncertainty weighing on base metal prices.

It’s certainly been enough to buoy copper, which spent much of last year under selling pressure from funds looking for a metallic trade-war trade. London Metal Exchange copper last week hit a nine-month high of $6,343 per tonne.

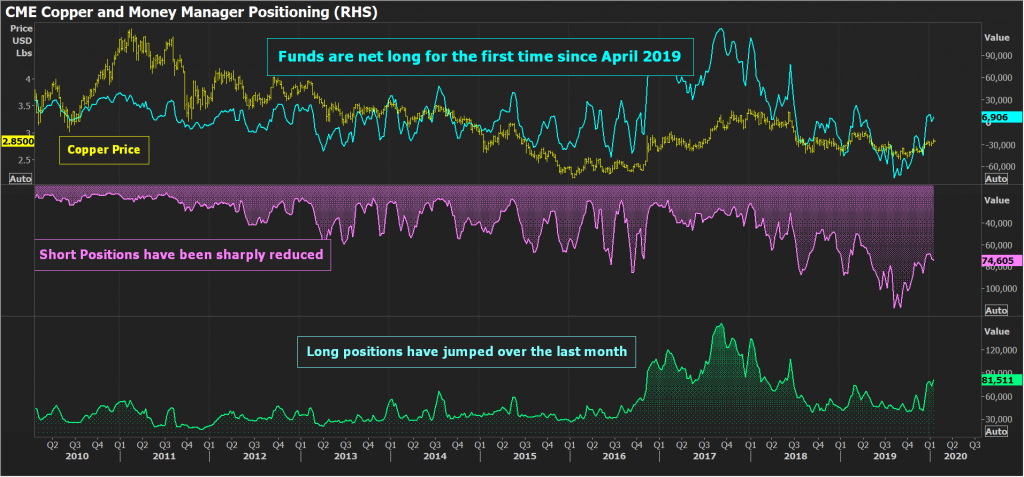

The money men have been buying copper since the start of December and are now net long of the CME contract for the first time in nine months.

The same holds true in London, with only the Chinese winding down activity ahead of the Lunar New Year holidays.

It helps that the break-out of trade peace, however temporary, is coinciding with a pick-up in Chinese industrial activity.

It also helps that copper’s fundamental market narrative is relatively bullish, unlike those of other metals such as aluminium.

Funds have been holding a net long position on the CME copper contract since the beginning of this year. The last time they were collectively this bullish was back in April 2019.

Macro negativity then turned the money men collectively short of copper, the bearishness reaching extreme levels in August and September.

That started changing during December as the prospect of a trade deal loomed. Funds turned net long of copper around the middle of the month and have stayed so since then, last week to the tune of 6,906 contracts.

The copper market this year will register the largest supply-demand deficit “seen over the past decade”

There has been some minor rebuild of shorts since the start of January, possibly because the copper price appeared to be losing upside momentum prior to the latest Commitments of Traders Report (COTR).

However, fluctuations in CME money manager short positions have been damped by the continued build in long positions. These reached 81,511 contracts last week, the biggest bull commitment since June 2018.

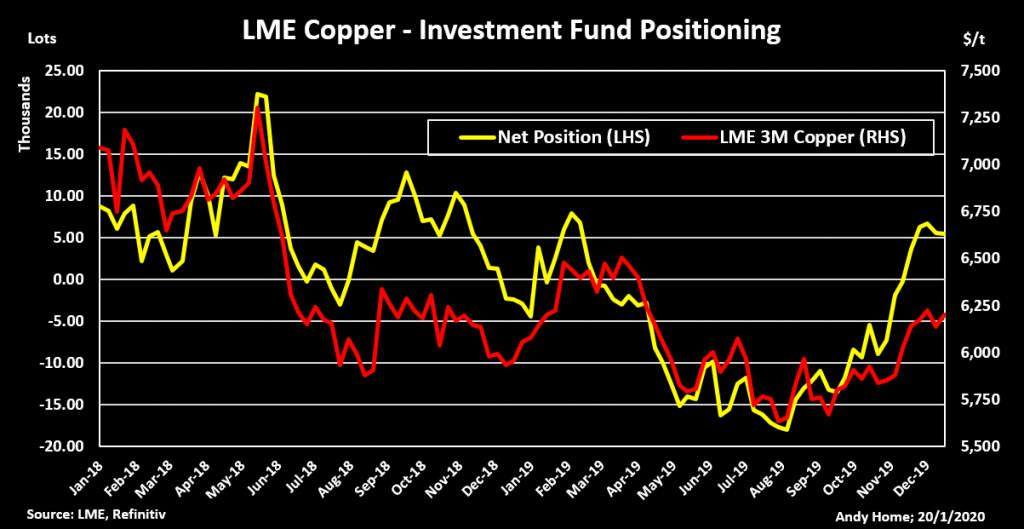

Something similar is happening in the London market.

The LME’s COTR figures show funds also turning net long of copper in December. As of the last report, up to the close of business on Jan. 10, “investment funds” held a collective net long position of 5,433 lots.

The LME’s “investment funds” category seems to capture shorter-term money flows. The category is well populated, with 155 entities in the last report, but with relatively small collective exposure.

Excluded are credit institutions and other longer-term players, although it’s noticeable that long positioning is also building in the LME’s “other financial” category, which includes pension funds.

Other analysts have their own methodology for assessing speculative positioning but everyone’s readings are pointing to the same movement of money.

LME broker Marex Spectron, for example, estimates speculators were net long of LME copper to the tune of 14% of open interest last Thursday. The range last year was a short of 12.7% in October and a long of 17% on Dec. 30.

Analysts at Citi assess positioning use a sliding scale from maximum short at zero to maximum long at 10 based on the last five years’ worth of positioning data.

They think cumulative copper positioning across both the LME and CME has gone from just one in August last year to a current seven.

Citi makes an interesting comparison with aluminium, where fund positioning has edged up only marginally from close to zero to a current two over the same time frame.

This might be because aluminium hasn’t historically played the same role as copper in reflecting broader market concerns, in this case the on-again, off-again trade talks.

It might also be because aluminium’s market narrative of Chinese over-production, high stocks and stuttering demand growth is hardly the stuff to set investors’ pulses racing.

Copper, by contrast, has a better bull story.

Supply has been struggling. World mine production fell by about 0.4% over the first nine months of 2019, according to the International Copper Study Group.

Exchange stocks are low. The LME, CME and Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) collectively held 302,400 tonnes at the end of December, down 48,000 tonnes on the year and the lowest end-month level since 2014.

The copper market this year will register the largest supply-demand deficit “seen over the past decade”, according to Colin Hamilton, analyst at BMO Capital Markets.

Analysts are pinning their bull hopes at least partly on confirmation that China’s giant manufacturing sector is starting to grow again

The key change from last year will be a modest recovery in demand both in China and, equally critically, the rest of the world, according to Hamilton.

“Our base case is for a modest recovery in 2020 demand (+2.2%), which in essence reflects simply an end to destocking,” he said.

“This will, however, divert some of the copper units away from Chinese buyers, and the resultant competition for units is what is needed to see further gains in the copper price.”

It’s a neat summary of the bull case for higher copper prices and helps explain why fund positioning has turned so fast in this market and not, say, in aluminium.

The only investors who don’t seem that impressed with copper right now are the Chinese, who are winding down ahead of the Lunar New Year holidays.

However, they haven’t been interested for some time. Volumes on the ShFE copper contract collapsed by 29% last year, part of a broader speculative retreat from the base metals sector in favour of the out-performing iron ore and steel markets.

December itself saw greater activity with copper volumes up for the first time in 2019, suggesting some impact from trade deal expectations and rising prices in London and New York.

The big question is whether copper returns to the Chinese investment radar after the New Year holidays.

Analysts are pinning their bull hopes at least partly on confirmation that China’s giant manufacturing sector is starting to grow again.

A pick-up in Shanghai copper trading volumes might be just as meaningful.

(By Andy Home; Editing by Jan Harvey)

Comments