‘Free money’ for banks as investors pile into fractured gold market

Banks are making huge profits from gold as investors flood into a market fractured by the coronavirus crisis.

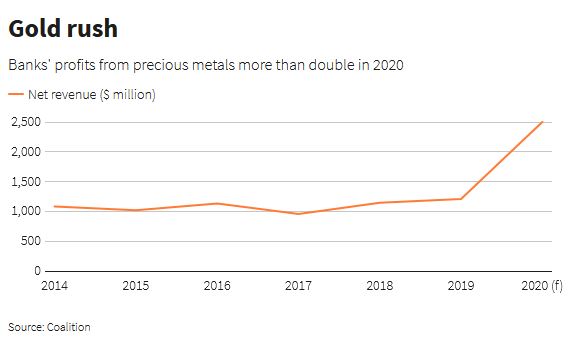

The world’s largest 50 investment banks are on track to double their income from precious metals this year to around $2.5 billion, most of it from gold, Coalition, a banking consultancy, told Reuters.

“$1.2 billion was the earnings pool last year. This year we already crossed that number,” said Coalition research director Amrit Shahani.

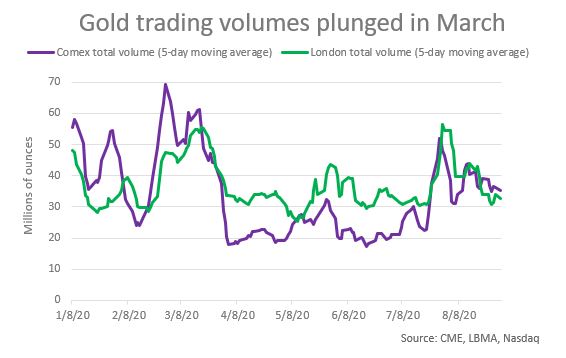

The juicy rewards, which have not previously been reported, mark a stunning reversal of fortune for bullion banks. In March, some had to wipe hundreds of millions of dollars off their trading books as the global pandemic snarled the supply of gold bars.

That disruption sowed the seeds for the current bonanza.

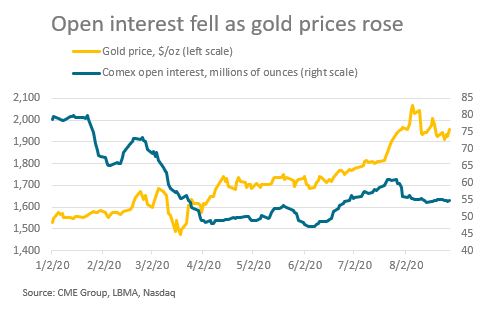

Stung by the losses, many big banks lowered their trading limits on the Comex exchange in New York, the biggest gold futures market, creating a lack of liquidity that pushed prices there above prices in London, the main hub for trading physical gold, and elsewhere.

Stung by the losses, many big banks lowered their trading limits on the Comex exchange in New York, creating a lack of liquidity that pushed prices there above prices in London

The divergence created a lucrative opportunity for banks who have the infrastructure to buy metal outside the United States and deliver it to New York to profit on the difference, especially during a pandemic, when investor demand has pushed gold prices to record levels of around $2,000 an ounce.

Reduced trading by large banks also drove prices of later-dated futures far above near-dated ones — an opportunity for those with gold to sell it forward for more than enough money to cover the cost of storage and capital.

The confluence of events has created a boom in profits on Comex, 13 sources at banks, brokers and funds told Reuters.

“It’s free money,” said an executive at one of the largest bullion-trading banks.

Even banks that reduced activity on Comex are making more money there than before, industry players said, none of whom was authorised to speak to the media.

“It’s double the profit on half the position,” a second banker said.

Banks, some hedge funds and asset managers that did little or no business on Comex have stepped up their activity, sources said and data from CME Group, which runs the Comex exchange, showed.

CME provides little data showing activity of individual actors on its market, but numbers that are available show banks including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Citi have ramped up trade in gold in vaults registered with the exchange in recent months, either delivering metal or accepting bars which they can sell forward.

Lenders such as Wells Fargo, BNP Paribas, Royal Bank of Canada and Barclays have also made or taken deliveries of gold against futures contracts after long periods of little or no activity.

With profits running high, not only from Comex but also from trading, financing and storing gold outside the futures exchange, some banks are hiring.

Deutsche Bank is adding a third person to its recently revived precious metals team, four sources said.

Citi, Bank of America, French lender Natixis and Australia’s Westpac have also hired in precious metals this year, according to sources and LinkedIn profiles.

The banks either declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment.

“We have seen strong growth in our precious metals markets this year, as new and existing customers use our products to manage uncertainty in today’s global economy,” said CME’s head of metals, Young-Jin Chang.

The cash and carry opportunity

Before the pandemic struck, banks such as HSBC and JPMorgan that dominate gold trading would buy metal in London and hedge their price risk by selling futures on Comex.

This allowed them to create liquidity in both places, but rested on assumptions that gold could quickly be shipped to New York if needed and that prices in the two markets would remain close together.

Those assumptions fell apart in March, when the virus shut supply routes. The link between London and New York ruptured, prices diverged sharply, and activity fell in both markets.

Futures prices became unmoored from London rates, sometimes trading cheaper but often $20 or more an ounce higher, and higher still compared to Asian countries.

With supply routes now reopened and the price premium outweighing the cost of making and shipping bars, which bankers say has ranged between $0.50 and $10 an ounce this year, more than 700 tonnes of gold worth some $45 billion at current prices has moved to New York since March, CME data show.

Before that influx, vaults registered with the exchange held less than 300 tonnes.

Flows of gold to the United States have begun to ebb, but another money making opportunity also opened in a transaction known as a roll, in which, every few months, investors in futures must swap expiring contracts for later-dated ones.

The scope for big profits has attracted more sellers into the market, from smaller banks to hedge funds and asset managers

To swap the February 2020 contract for the April one cost around $6 per ounce of gold, CME and Refinitiv data show — or around $240 million in total for the roughly 400,000 100-ounce contracts trading.

When the London-futures connection broke and banks became reluctant to sell in unlimited quantities, the price rose. To roll from June to August cost around $15 an ounce on average. The longer, four-month roll from August to December cost $25 an ounce — or $1 billion in total for 400,000 contracts.

A boon for the seller, the market is costly for futures buyers.

“There is no free lunch,” said a source at a large U.S. bank. “Somebody has to lose money along the way … those people (with long positions) are every time paying money to those willing to take the other side.”

The scope for big profits has attracted more sellers into the market, from smaller banks to hedge funds and asset managers.

A further uptick in futures supply could eventually temper profits, particularly if it’s accompanied by a drop in demand, but in the meantime, banks are coining it, both by managing their own trading books and facilitating trades by new entrants.

“The amount of business we’ve done with hedge funds around this is unprecedented,” said one banker, adding that his desk’s profits from gold were already double last year’s total.

“It’s a glaringly obvious cash and carry opportunity.”

(By Peter Hobson; Editing by Veronica Brown and Carmel Crimmins)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments