Don’t expect a crisis to be good for gold

Here’s another factor to add to the gyrations in the gold price over the past few weeks: The biggest players in the market may be losing their buying appetite.

Russia’s central bank, one of the world’s largest gold buyers in recent years, is halting all purchases of the metal. It’s not alone: Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, whose central banks have also been reliable consumers of late, have also slowed down. Rolling three-month additions to official sector gold holdings (those held by central banks and international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund) in January amounted to just 67 metric tons, the slowest pace since August 2018.

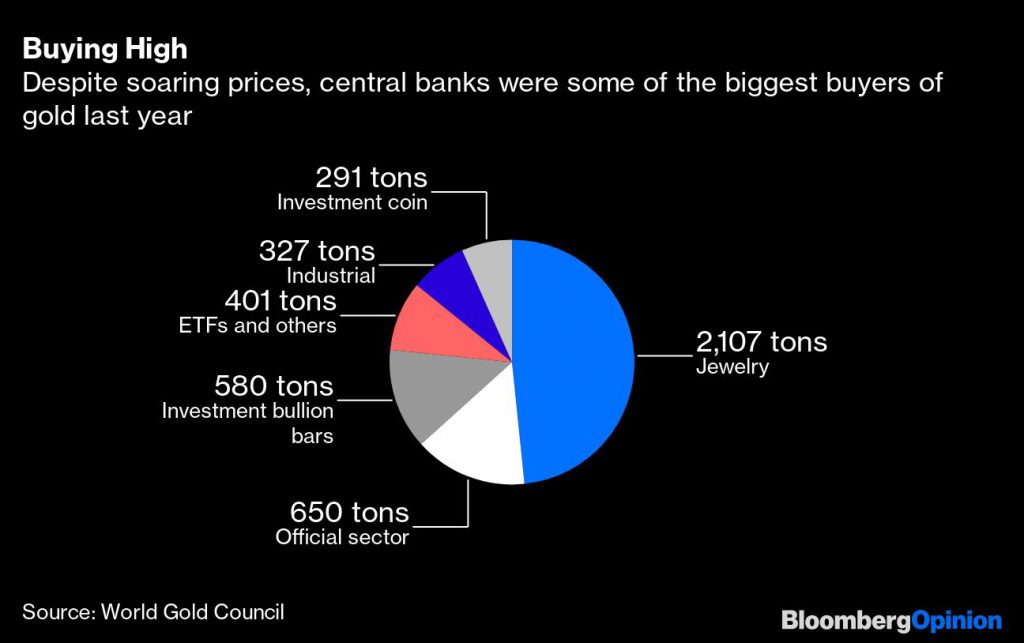

The official sector owns about a fifth of the gold that was ever mined, and was the biggest buyer last year after jewelry consumers. The last time it turned a net seller, in the 1990s and early 2000s, gold prices cratered. Should history repeat itself, the current spike in the market would quickly wilt.

It’s hardly surprising that the world’s most solid institutions should be holding back on purchasing a flight-to-safety asset at a time when nervier private holders are driving up its price. Purchasing bullion when it’s close to a seven-year high, and after a month of prices fluctuating through a range of about 13%, doesn’t seem a particularly smart way to add stability to your portfolio.

It might be argued that the current crisis is precisely the sort of emergency that proves the enduring value of gold for a central bank, as an asset with no counterparty risk that can be sold in an exchange for any currency if things get tight. There are two problems with that as a case for buying now.

In the short term, gold is only valuable in a crisis to the extent that you’re prepared to sell it. Any countries facing shortages of foreign currency to manage their balances of payments should be liquidating metal at the moment, rather than adding to their holdings.

In the longer term, the Federal Reserve’s announcement Tuesday of a temporary facility allowing central banks to swap their Treasury holdings for cash blows up even that argument. In a world that still runs on the dollar, the prime attraction of gold is the ease with which it can be exchanged for greenbacks. So long as the yield on Treasuries doesn’t drop to zero, they’ll represent a more attractive way of raising cash dollars for as long as those swap lines are open.

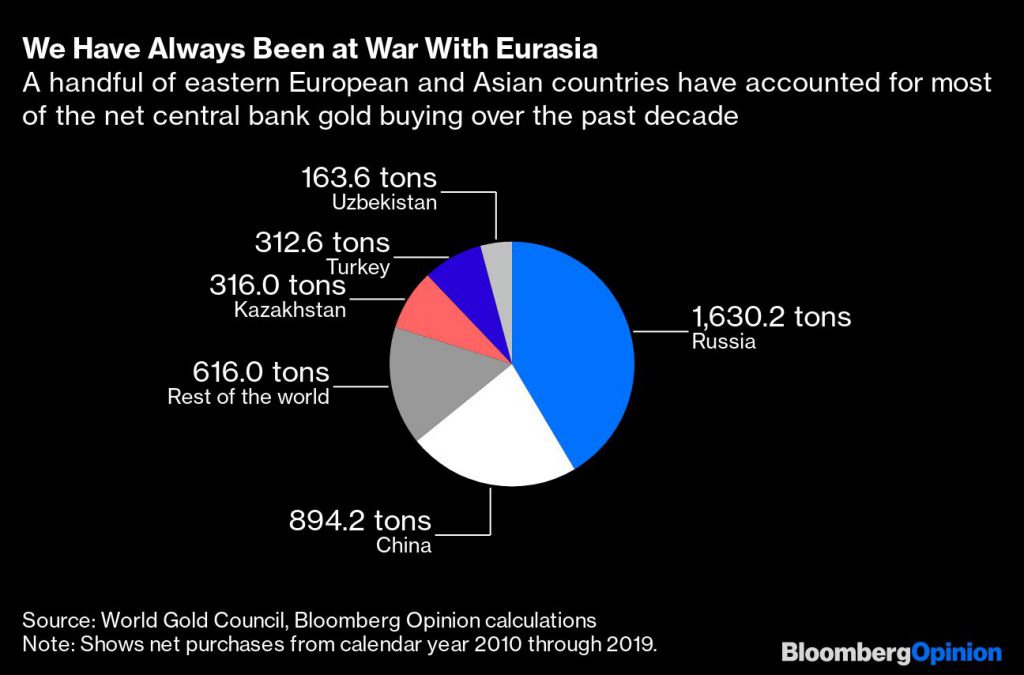

The appetite for official gold buying over the past decade has come from a surprisingly small club of mainly emerging economies. Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Poland and Mexico alone have accounted for about 90% of net purchases.

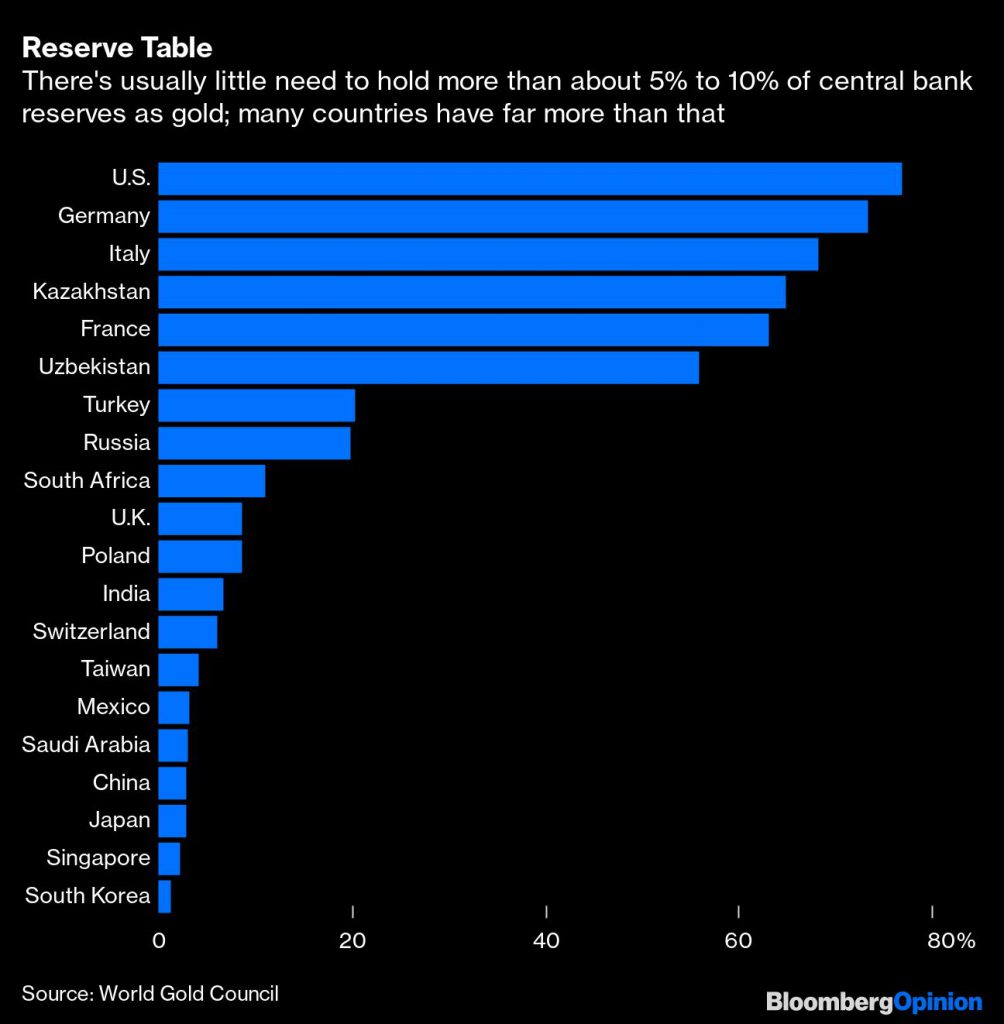

Most of those players have now reached levels where their appetite is likely to be exhausted. The two central Asian republics now hold more than half of their reserve assets as metal, well in excess of what they’d need to balance out their portfolios and manage currency risks. Turkey’s holdings at the end of December were equivalent to around 20% of its reserves, hard against the upper bound of new gold reserve limits announced in January. Russia has sworn off further purchases for the moment and Mexico has mostly been a seller in recent years.

It’s not impossible that other central banks might see things differently.

At 9% of reserves, Poland’s holdings look ample in principle, but recent policies such as the repatriation of nearly half its gold from London seem driven more by symbolism than economics. (In terms of liquidity management, you should want your gold to be based in an overseas bullion-trading center like London or New York, rather than Warsaw.)

More to the point, the major economies in east Asia continue to have reserves in the lower single digits, making the region one of the few where holdings are arguably lower than optimal. Any switch to more aggressive purchases by the likes of China, Japan, Taiwan or South Korea would deliver fresh support to the market.

Still, it’s worth reflecting that the surging price of gold is increasing the share of bullion in most central banks’ reserves right now, in some cases to the point where they need to think about selling.

It’s easy to forget that 20 years ago, official sector gold sales were regarded as undermining prices so severely that European banks struck an agreement to limit and coordinate their disposals. That deal, in turn, sparked a rally leaving sellers such as the British and Swiss central banks looking like the worst precious metal traders in history.

The agreement lapsed last year with the expectation that it was no longer needed in a world where governments’ hunger for metal looked insatiable. It would be typical of the ironies in the gold market if this safety net were abandoned just at the moment that it’s needed most.

(By David Fickling)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments