Distraction or disaster? Freeport’s giant Indonesian mine haunted by audit report

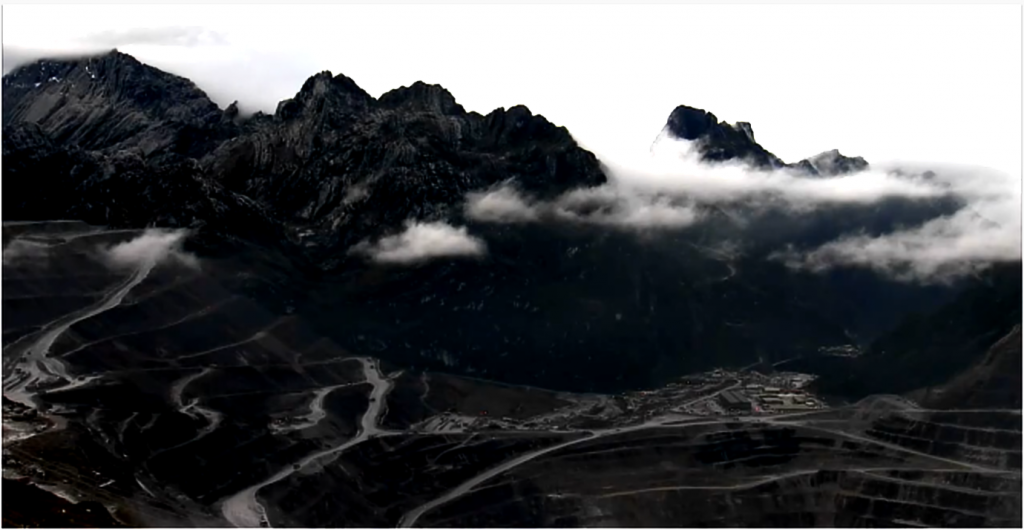

JAKARTA (Reuters) – A state audit of operations at Indonesia’s Grasberg mine has cast a cloud over the government’s multi-billion-dollar deal to take a majority stake in the mine from Freeport McMoRan Inc (FCX.N) and its partner Rio Tinto (RIO.AX), according to government and company officials.

In April, in follow-up action to the audit, the environment minister issued two decrees that gave Freeport six months to overhaul management of its mine waste, or tailings, at Grasberg, the world’s second-biggest copper mine. One of the decrees said Freeport would be barred from any activities in areas that lack environmental permits.

And there may be more troubles to come for the Phoenix, Arizona-based company as the government has so far acted on only a part of the 2017 report by Indonesia’s Supreme Audit Agency (BPK) on Freeport’s decades-long operations at the mine in Indonesia’s remote easternmost province of Papua.

A letter from Freeport CEO Richard Adkerson to the environment ministry, a copy of which was reviewed by Reuters, said the decrees imposed “undue and unachievable restrictions” on Freeport’s basic operations.

In a separate letter to the government, quoted by Tempo magazine, Adkerson said: “I am deeply concerned that these actions have the potential to derail the progress that all of us have worked so hard to achieve.”

Freeport officials declined to comment on the letters. Officials at the mining and environment ministries confirmed that letters from Adkerson were received, but did not provide detail on their contents.

Officials at the mining and environment ministries confirmed that letters from Adkerson were received, but did not provide detail on their contents.

In a call to analysts last month, Adkerson had played down the impact of the decrees. “This is a distraction, but you all know over time we have to deal with political issues, and this is one of them,” he said.

“We don’t see anything to interfere with our operations. The government needs and desires now to make sure that we continue to operate and they collect their taxes and royalties.”

The biggest problem for both the government and the U.S. company may be the additional findings in the BPK report that are yet to be taken up. It asserted that Freeport caused environmental damage worth $13.25 billion, missed royalty payments, cleared thousands of hectares of protected forest and began mining underground without environmental clearance.

Pressure is mounting on the government to take more action.

Kardaya Warnika, an opposition party member who chairs parliament commission VII, which oversees the mining sector, said the government and parliament were both obligated to follow up on the audit findings.

If Freeport is found to have royalty shortfalls, “then they should pay,” Warnika said.

Sonny Keraf, a former environment minister who led talks on Indonesia’s 2009 mining law, said the government needs to follow up on the BPK report “comprehensively”.

Stuck

Indonesian state mining holding company PT Inalum is due to take over the majority stake in Grasberg under a long-heralded acquisition deal, which has to be completed by 2019.

Under the proposed transaction, Rio Tinto (RIO.L), which has a stake in Grasberg’s output, would sell its interest to Inalum, which would be converted to equity.

Freeport, which would sell Inalum a further 9.36 percent stake, would see its current 90.64 percent holding in Grasberg diluted down to 49 percent, although it would remain the mine’s operator.

Last week, Inalum CEO Budi Gunadi Sadikin told reporters discussions on the acquisition were being held up by “several” environmental issues. Freeport had “made breaches that need to be revised through the environmental audit,” Sadikin said. “The biggest issue is the issue of tailings – that has to be improved.”

Environment Minister Siti Nurbaya told reporters on Wednesday she had met Adkerson for a three-hour meeting last week to discuss the decrees on the tailings. No decision was reached and the ministry will hold regular meetings to resolve the matter, although Freeport will meanwhile be allowed to continue to operate, she added.

But with Jakarta’s political climate likely to get increasingly tense ahead of the 2019 presidential elections, the government may not be in a position to work out a compromise with the company, political analysts said.

While the BPK report’s recommendations are not binding, they could be turned into political “ammunition to undermine” President Joko Widodo ahead of the election, said Achmad Sukarsono, an analyst at the Control Risks consultancy.

That would make it increasingly difficult for Widodo to finalize a deal for a majority government stake in Grasberg before the audit issues are resolved, he added.

For Widodo, getting a majority stake for the Indonesian government in one of the world’s biggest mining operations under his watch would be a political boon.

A spokesman for the president’s office deferred questions on the matter to Widodo’s chief of staff, who did not respond to a request for comment.

The mining ministry directed questions on the BPK report to the ministry’s environmental director, who did not respond to requests for comment.

Freeport “has responded to the relevant matters in the BPK report,” the company said in a statement in response to Reuters questions, declining to comment further.

No certainty

Freeport began exploration in Papua in the late 1960’s and, helped by ties to late President Suharto, clinched a deal to mine Grasberg in 1988.

The company is now one of Indonesia’s biggest taxpayers.

The issue of what will happen to Grasberg when Freeport’s contract there expires in 2021 has dogged the company for years.

In an effort to end years of wrangling, Freeport pledged last August to transfer majority ownership of Grasberg to Indonesia in return for rights to mine the deposit up to 2041.

That deal is critical to Freeport, whose underground expansion plans for Grasberg require billions of dollars in further investment, particularly as open pit mining there is slated to end this year.

(Reporting by Bernadette Christina Munthe; Additional reporting by Susan Taylor in Toronto; Writing by Fergus Jensen; Editing by Raju Gopalakrishnan)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments