Deutsche Bank sticks out among financiers of Peabody’s coal loan

When Peabody Energy Corp. agreed to buy the coal assets of Anglo American Plc, only one European lender joined the US investment bankers and private credit specialists financing the deal: Deutsche Bank AG.

Peabody obtained a $2.1 billion bridge loan to help it pay for the acquisition, according to a Nov. 25 filing. Behind that loan are divisions of KKR & Co., a unit of Jefferies Financial Group Inc. and Deutsche Bank. Of the firms providing financing, only Deutsche Bank has published an explicit policy on coal.

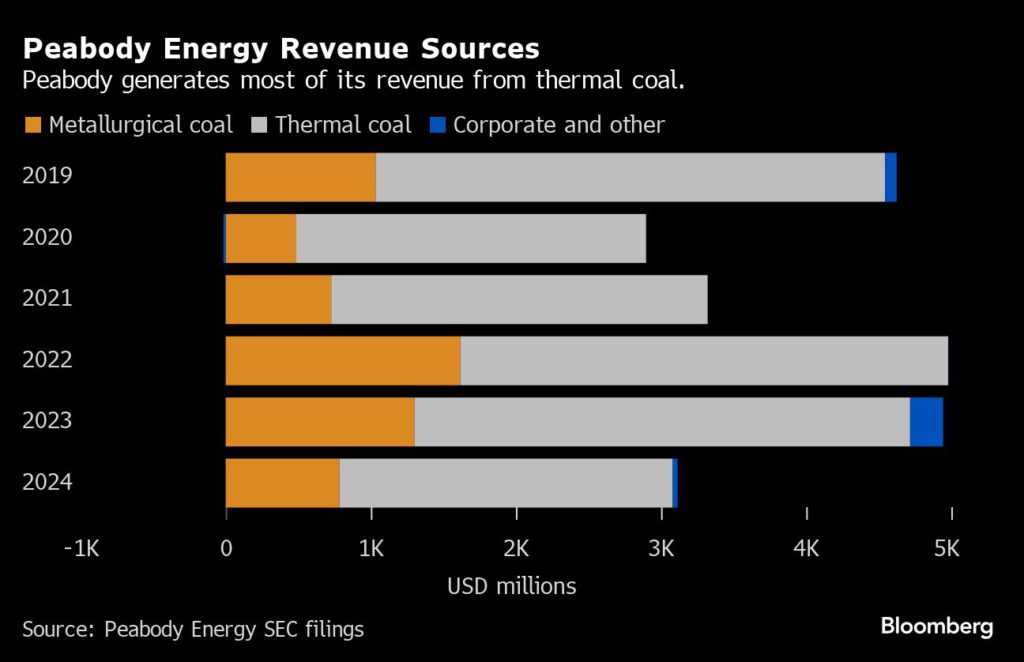

At issue is the extent to which the financing crosses a line at the German bank, whose exclusion policy singles out the thermal coal used for heating and electricity. The mines Peabody is acquiring produce mostly metallurgical coal, which is used in the manufacture of steel. But the company produces both types of coal across its operations and one of the mines being acquired produces thermal coal.

A spokesperson for Deutsche Bank said any business it does involving coal is closely analyzed and all transactions are in line with its exclusion policy.

But climate activists say the distinction between different grades of coal is arbitrary, and ultimately irrelevant when it comes to measuring environmental damage.

“Coal is coal regardless of its end use,” said Cynthia Rocamora, an industry campaigner at climate nonprofit Reclaim Finance. All types are “extremely polluting and need to be phased out,” she said.

Coal that’s broadly classified as metallurgical — often called met coal — can be sold in thermal-coal markets. In fact, it’s something that happens regularly for lower quality metallurgical products like pulverized coal injection (PCI) and semi-soft coking coal, according to Alexandre Claude, chief executive of DBX Commodities, a dry-bulk tracking firm.

The switch was particularly common in 2022 after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended pricing. From Europe to Asia, utilities took delivery of met coal to fire power plants as the cost of thermal coal surged.

Vic Svec, vice president of investor relations at Peabody, said “a small amount of crossover volumes by any metallurgical coal producer is always possible.” He also said there’s a “very high probability” that the coal from the mines Peabody is acquiring from Anglo American will go to steel markets.

In a February filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, Peabody said it “may market some of its metallurgical-coal products as a thermal-coal product from time to time.”

Details of the Peabody loan

Peabody secured a commitment letter from Deutsche, Jefferies and KKR to provide up to $2.08 billion to finance its acquisition of Anglo American’s coal mines. Peabody said in its public disclosure that the bridge loan facility isn’t expected to be drawn in full if future equity offerings and additional debt placement are successful. The company’s expectation is that it will “reduce the bridge commitments through such offerings or financings, possibly to zero, prior to the closing date.”

In practice, most met-coal mines produce some thermal coal as a byproduct meaning companies can’t reasonably claim to be pure-play met-coal producers. And since money is fungible, financing one type of coal asset can end up bankrolling the other.

However, coal producers and the financial institutions backing them have long sought to distinguish between metallurgical and thermal coal. Most banks and asset managers treat the former as a more acceptable risk because of the role it plays in the production of the steel needed to enable the clean-energy transition.

In reality, metallurgical coal can be up to three times as polluting as thermal coal, according to Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy. It’s also possible to produce steel without coal. So-called green steel can be manufactured using alternative energy sources, with BloombergNEF estimating that the combination of hydrogen and recycling will help spur a tenfold increase in production through 2030. That’s why some financial firms have started to adjust exclusion policies beyond just thermal coal.

Data collected by Reclaim Finance show that of 99 banks it analyzed, nine have adopted metallurgical coal policies, including BNP Paribas SA and Macquarie Group Ltd. And Zurich Insurance Group AG became the first insurer to add restrictions on metallurgical coal mining earlier this year. Meanwhile, 372 of 386 financial firms analyzed by Reclaim Finance have policies targeting thermal coal only.

Data compiled by nonprofit Urgewald show that US and Chinese banks provide the most coal finance, with Jefferies standing out as having significantly ratcheted up deals in recent years.

In Europe, Deutsche Bank made smaller cuts to its coal exposure between 2016 and 2023 than peers, Urgewald data show. For example, while UBS Group AG and BNP reduced their exposure over the period by 77% and 67%, respectively, Deutsche Bank cut its coal financing by just 4%. To be sure, Deutsche’s starting point in 2016 was meaningfully lower. But by the end of 2023, it was financing 50% more coal than BNP, and 29% more than UBS, the data show.

At the same time, thermal-coal companies that diversify into metallurgical production are finding it easier to get financing. Whitehaven Coal Ltd., one of Australia’s largest producers of the commodity, gained better access to insurers after announcing its move into met coal, Bloomberg has reported.

And Peabody, which had seen large banks such as JPMorgan Chase & Co., UBS and Bank of America Corp. retreat from its financing in recent years, is now finding that it has easier access to capital.

“We see expanding access to all aspects of the investment community based on the dramatic transformation of Peabody into a company with three-quarters of its cash flows coming from metallurgical coal,” Svec said.

Some banks, including Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Jefferies, have stuck with the company throughout, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Spokespeople for Macquarie, JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Jefferies and UBS, which took over Credit Suisse last year, declined to comment.

Nonprofits also have identified instances in which companies have downplayed the portion of coal production that’s thermal. Whitehaven Coal, for example, “greatly overestimated” its metallurgical, or coking, coal output at two mines in Australia, according to Market Forces, a nonprofit, and Energy & Resource Insights, a consultancy. And Bharat Coking Coal Ltd., a subsidiary of Coal India Ltd. that says it specializes in metallurgical coal, sent 68% of its production to power-sector customers in the financial year ended March 31, according to its annual report.

A spokesperson for Whitehaven declined to comment. Bharat didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“Given the uncertainty of what the end use is going to be for each type of coal, a safe approach is to just restrict financing for any type,” said Rocamora of Reclaim Finance. “The differentiated approach between met and thermal coal shouldn’t exist.”

(By Natasha White)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments