In the country where coal is king, a battle with the EU looms

The buzzword in the Brussels energy and climate bubble is 450, a number that is dividing European Union lawmakers and making coal-dependent Poland fume over upcoming reforms to the world’s biggest carbon market.

“There is a risk that the ETS modernization fund for eastern member states may unintentionally support considerable investments in carbon-intensive electricity production,” Ronald Busch, managing board member at Siemens, said in an interview. “Setting a CO2 limit would bring investments in line with Europe’s climate ambition.”

The principle of the cap-and-trade system is that companies emitting less than their quota can sell their unused permits, getting a financial incentive to become cleaner. The overhaul aims to adjust the program to the 2030 climate goal and to bolster the price of allowances after they lost nearly 70 percent over the past nine years. Benchmark EU permits traded at 7.90 euros per metric ton on Friday compared with the 25-to-30 euro target lawmakers had in mind when they were designing rules for the 2013-2020 phase of the market.

The emission performance standard of 450 grams carbon-dioxide was the biggest sticking point at the previous round of talks between the representatives of EU governments and the European Parliament on Oct. 12. After 13 hours of talks, negotiators left the meeting around 3 a.m. without reaching a deal. Estonia, which leads the talks on behalf of EU member states, demanded the number be removed, offering instead a provision to ensure spending under the modernization fund is in line with the Paris Agreement goals. The team from the European Parliament didn’t want to give up on the 450 grams.

The Polish government and the Eastern European country’s energy companies including PGE SA have demanded an increase of the modernization fund and argued that they need time and money to shift from coal to greener energy sources without undermining the security of the power supply. An emissions performance standard would force utilities to build new natural gas plants, which they argue still produce greenhouse gases and would increase Warsaw’s dependence on gas from Russia.

To read more about reforming the EU’s cap-and-trade program, click here

“It seems that it will be difficult to reach an agreement in the Council of the EU,” Szydlo said in Brussels after an EU summit last month. “We’re still holding to hope that it will be possible. If not, I will propose that those disadvantageous proposals by the European Commission be discussed at an EU summit because they are very unfavorable for Poland and for a large group of countries.”

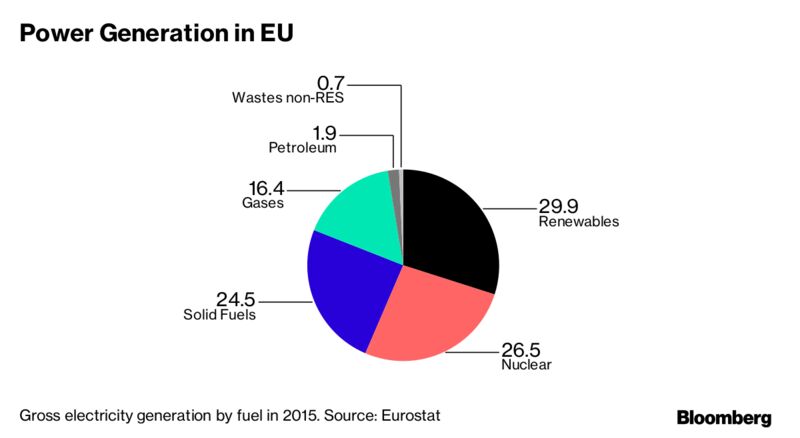

The modernization fund was set up to help 10 lower-income member states, with gross domestic product per capita below 60 percent of the EU average, modernize their energy infrastructure and reduce greenhouse gases. In the run-up to the Nov. 8 meeting, seven EU nations including France, Germany, Sweden and Denmark, suggested a compromise provision that would prevent using the fund to support “solid fossil fuels-based energy generation.”

“To the extent that this is made clear, we are open to alternative ways to formulate such appropriate safeguards,” the countries, which also include Luxembourg, Netherlands and the U.K., said in an informal document presented to Estonia and obtained by Bloomberg News.

Any compromise on the carbon-market overhaul will come in the form of a package that balances the need for bolstering the market, protecting the competitiveness of European companies and ensuring financing for modernization, EU lawmakers have said. In September, the negotiators provisionally agreed on the first element by approving strengthening of a special reserve that will alleviate oversupply of permits.

For Estonia, the holder of the rotating EU presidency until the end of this year, the reform is one of the most important issues on the table.

“EU ETS is the cornerstone of our climate policy and it needs a reform to ensure that the system functions well. This is, however, not an easy puzzle to solve,” said the presidency spokeswoman Annikky Lamp. “Our goal is to reach an agreement during the Estonian presidency, but as the latest 13-hour negotiation round illustrates, it’s a challenge.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments