Copper bears beware as strike risks rise in top producer Chile

(Bloomberg) — Copper forecasters are reassessing their projections as the top-producing country prepares for its busiest year ever for wage talks.

Under a new labor code and with higher prices inflating workers’ pay expectations, Chilean mines will negotiate contracts with 32 unions next year. That represents about three-quarters of the country’s copper output, or about one-fifth of world production. Globally, labor negotiations could trigger disruptions at mines producing about 40 percent of supply, according to Barclays Plc, which this week raised its price estimate.

While prospects of slower Chinese demand growth have sent copper back below $7,000 a metric ton in the past few weeks, supply is also constrained after years of cutbacks spurred by low prices.

That means any disruptions resulting from strikes could quickly tighten up the market — as happened this year with stoppages at Escondida in Chile and Grasberg in Indonesia. If that occurs, prices could go back above $7,000 in the first half of the year, Bank of America Corp. analysts said last week.

“It’s going to be pretty tough,” Andrew Cosgrove, senior energy and mining analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, said by telephone. “Copper price risks mainly come from the Chinese property sector, but the Chilean negotiations add a thicker layer of price support.”

He expects supply to increase by 200,000 to 300,000 tons next year, signaling a fairly balanced market. But a repeat of this year’s strike interruptions would easily wipe out that increase. “Given how many negotiations are on, it could be even worse.”

While workers in Southern Copper Corp. mines in Peru returned to work on Tuesday after a 20-day strike, one union at Teck Resources Ltd.’s Quebrada Blanca mine in Chile were preparing to go on strike in what would be the first stoppage under the country’s new labor code.

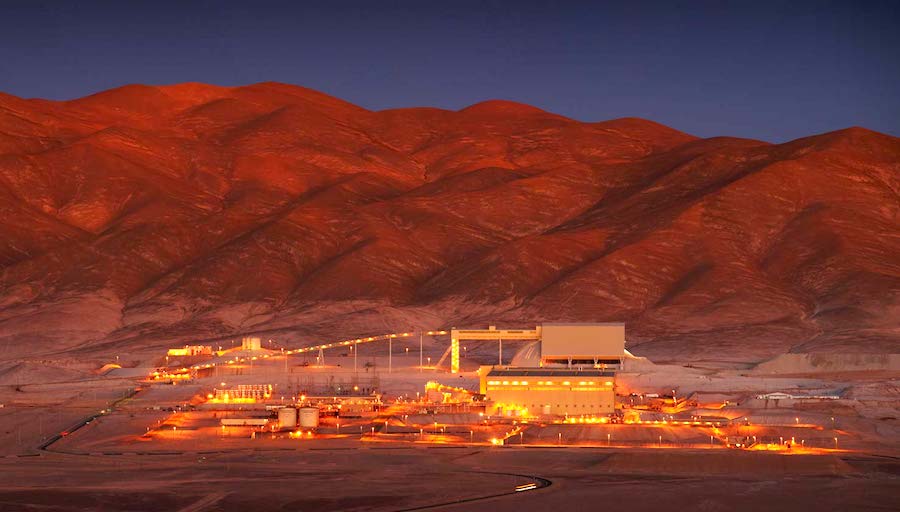

Most of Chile’s largest mines face wage talks next year, although much of the attention will be on BHP Billiton Ltd.’s Escondida. The longest mine strike in the country’s modern history ended in March with no accord and an extension of the old contract until June 2018. Tensions ran high during a stoppage in which workers set up camp at the mine entrance, displaying dummies hanging from ropes representing executives and recording videos burning company letters.

An announcement by BHP in November to cut 3 percent of Escondida’s workforce spurred a 24-hour strike and threats of further action, with unions calling the layoffs an act of intimidation ahead of next year’s wage talks.

“Under the labor reform that came in last April, there is no downside for the employees during the negotiations,” said Cesar Perez-Novoa, an analyst at BTG Pactual in Santiago. “Unions are empowered and this will influence negotiations. They are better prepared from a legal and economic point of view.”

“Workers have made sacrifices over the last two years,” said Gustavo Tapia, president of Chile’s Mining Federation, which represents more than 20 unions from the largest mines. “Everyone can see that prices and production are higher, so the talk of crisis is no longer relevant.”

At the highest point of the last commodities cycle, juicy end-of-conflict bonuses were at the center of the talks. Now, negotiations are more likely to focus on benefits, Tapia said. Unions won’t be making unreasonable demands, he said, but they will ask for what they deserve after years of cost cutting.

“We need to have this discussion in a responsible manner,” Tapia said. “If companies keep talking about crisis, the answer will be to strike. And if they don’t understand that, this could be a year of many stoppages.”

While copper prices are about 14 percent higher than a year ago, volatility over the last few months will mean companies will tread with caution, according to Diego Hernandez, president of Chile’s mining association, Sonami. On the other side, unions might have learned a lesson from the Escondida strike, which ended with no agreement, no end-of-conflict bonus for workers and a salary freeze that will only end when the new contract is signed.

“We are confident that workers will act realistically and with moderation in these negotiation processes,” Hernandez said in written answers to questions. “There is a need to act with caution, especially considering that investment hasn’t been strong enough to reverse the fall in employment that happened over the last few months.”

With higher copper prices and empowered unions, companies should try to sign early wage agreements with their workers, said Colin Hamilton, a managing director of commodities at BMO Capital Markets in London. “Unions are willing to sit and wait because there’s no urgency on their side. They have a lot more leverage.”

Last month, Antofagasta Plc failed to reach an early agreement with workers at its Los Pelambres mine after five weeks of talks. Formal negotiations will start Jan. 2, when the union presents its contract proposal, making it the first negotiation of the year. The company, which has never had a strike at any of its mines, declined to comment on the talks and said they are a normal part of the collective-bargaining process.

Codelco avoided strikes in all of its wage negotiations this year. The state-owned company — whose Chief Executive Officer Nelson Pizarro famously said it didn’t have “a single f—–g peso” — signed contracts with no real wage increases and austere bonuses. On Tuesday, Pizarro reiterated that any wage increases would have to be tied to productivity improvements.

Strikes could affect about 4.2 percent of the world’s total copper production, Hamilton said. But that percentage could increase given the number of union contracts up for renegotiation next year.

“We are projecting a very tight copper market by mid-2019,” Hamilton said. “The focus is on the supply side of the equation and any problems there would mean that tightness could be pulled forward if we have significant disruption.”

Story Laura Millan Lombrana

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments