Column: New fund friends will find lead in unusually lively mood

Lead has just joined the commodity A-list, bringing a new set of players to a market that has been trying to rebalance supply and demand for two years.

Although commanding a weighting of just 0.936%, lower than any other industrial metal, lead is included in the Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM) for the first time this year.

Lead’s entry in one of the most widely-tracked benchmark indices will generate a significant investment booster during the BCOM January roll window which starts on Monday.

The new fund flows arrive at a time of unusual volatility in what has historically been a relatively staid and stable market.

The London Metal Exchange (LME) three-month lead price has rebounded from a September low of $1,746 to a current $2,290 per tonne, partly thanks to its BCOM inclusion.

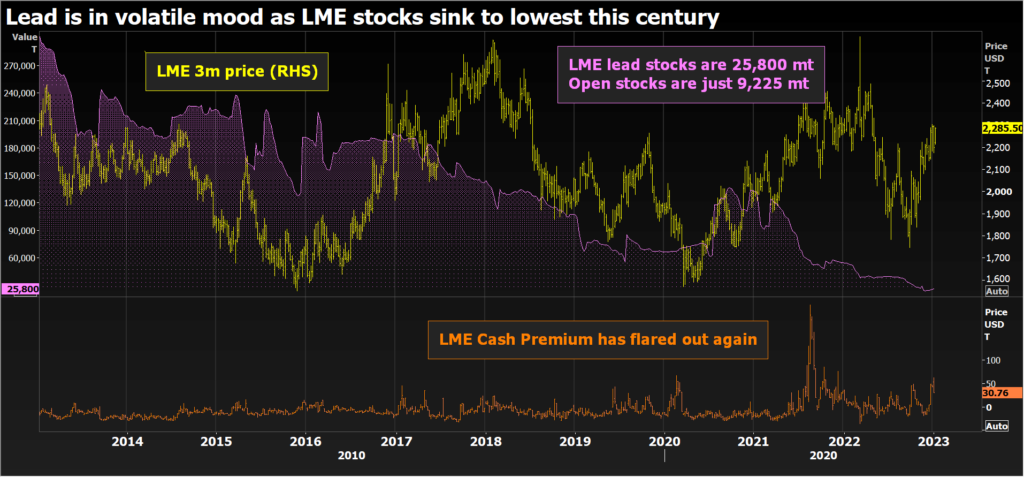

Depleted LME inventory, which has slumped to its lowest level this century as a two-year physical supply squeeze shows every sign of rolling into the new year, has also helped.

Stocked out

LME lead stocks fell by 54% to 25,150 tonnes over the course of last year. The headline figure has recovered slightly to 25,775 tonnes after some warranting activity last week at the Taiwanese port of Kaohsiung.

However, a string of cancellations in late December means that 64% of that metal is now awaiting physical load-out.

Live tonnage is just 9,225 tonnes, the lowest this century and equivalent to around six hours’ worth of global usage.

Time-spreads are unsurprisingly volatile, the LME cash premium over three-month metal flexing out to $63 per tonne at one stage last week, its widest since December 2021.

The distribution of LME warehouse stocks says a lot about the underlying stresses in the physical supply chain.

All the remaining available volume is located in Asia with the bulk in Kaohsiung. There are no registered stocks in the United States and just 1,775 tonnes in Europe, all of it cancelled.

European and North American markets have been tight for over two years due to a sequence of smelter hits, most notably the loss since mid-2021 of the Stolberg smelter in Germany.

The International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG) estimates that refined lead production slid by 1.3% year-on-year in the first 10 months of 2021, pushing the global market into a 46,000-tonne supply deficit, compared with an equivalent 48,000-tonne surplus last year.

China to the rescue?

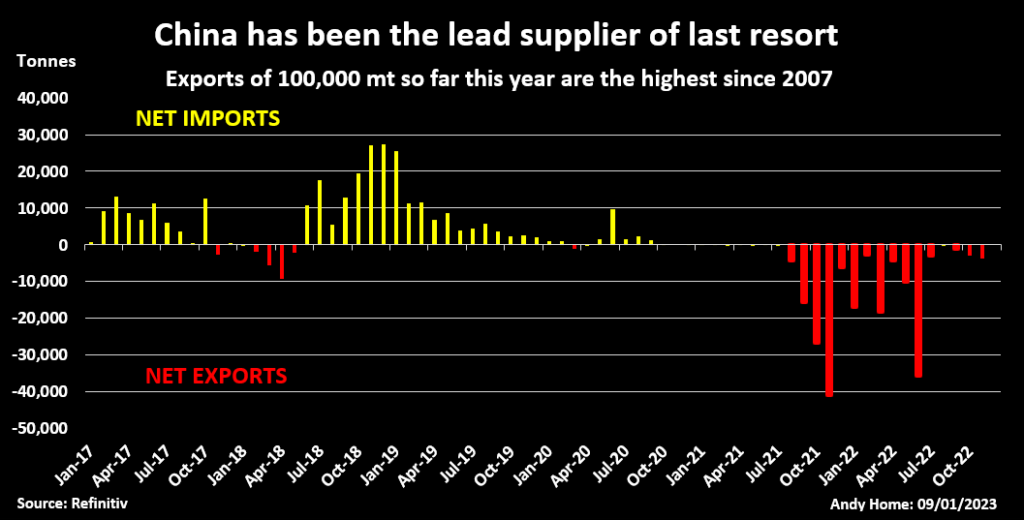

China has emerged as a supplier of last resort to a stretched Western market.

The country was a modest net importer of refined lead in the 2017-2020 period but that changed in 2021 as exports mushroomed to 95,000 tonnes, the highest annual total since 2007.

The export surge continued last year with outbound shipments totalling 100,040 tonnes in January-November. They included a 15,000-tonne cargo to Turkey in January, an 11,000-tonne dispatch to the Netherlands in March and a 30,000-tonne shipment to the United States in June.

All are highly unusual destinations for Chinese exporters, attesting to the economic incentive created by positive arbitrage and high physical premiums.

However, the pace of exports appreciably slowed over the second half of 2022 with lower tonnages heading to more routine destinations such as Taiwan, South Korea and Vietnam.

Shanghai is no longer sitting on a mountain of lead. Stocks registered with the Shanghai Futures Exchange (ShFE) were over 200,000 tonnes in September 2021. They currently stand at just 37,925 tonnes.

Exports of refined metal have obviously played their part in that inventory reduction. But so too have exports of lead-acid batteries.

China’s zero-covid policy last year did not help vehicle sales, a core component of lead’s usage profile. The China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) in July cut its forecast for 2022 sales growth to 3.0% from 5.4%. Sales through November were tracking that forecast with 3.3% growth on 2021.

Chinese battery-makers have compensated by turning to the export market. Exports hit a record 199 million units in 2021 and were up another 10% year-on-year in January-November last year, more than offsetting any domestic weakness.

Battery export demand has helped underpin domestic usage, while the shipment of almost 200,000 tonnes of primary refined metal to Western markets over the last two years has left China’s own inventories looking depleted.

It’s highly uncertain if China has the capacity to keep plugging Western supply-chain gaps going forwards.

Rebalancing

The lead market that has been trying to rebalance for two years and the return of Nyrstar’s Port Pirie smelter in Australia after three months of maintenance should help.

Still missing in action, though, is the 155,000-tonne per year Stolberg plant, which is in the process of being purchased by trade house Trafigura and which will be managed by Nyrstar. Although repairs to the 2021 flooding have been completed, a restart is dependent on regulatory approval of Trafigura’s purchase which is still pending.

Lead demand, meanwhile, will be determined by the state of play in the automotive sector with Chinese recovery playing out against European recession.

It’s worth remembering, though, that lead is in part insulated from the broader economic cycle by the need for replacement batteries, which tend to fail every few years, particularly in the sort of wintry conditions that have just hit North America.

What normally acts as something of a price cushion for lead may this year accentuate the continuing supply-demand imbalances in Western markets.

The ILZSG’s most recent October forecast was for another consecutive year of supply shortfall in 2023 to the tune of 42,000 tonnes.

Lead’s new fund friends could be in for a turbulent ride before a return to the more pedestrian performances of the past.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Alexander Smith)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments