Column: Indonesian tax will shake up the nickel export mix again

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

Indonesia’s planning to reshape the global nickel market again.

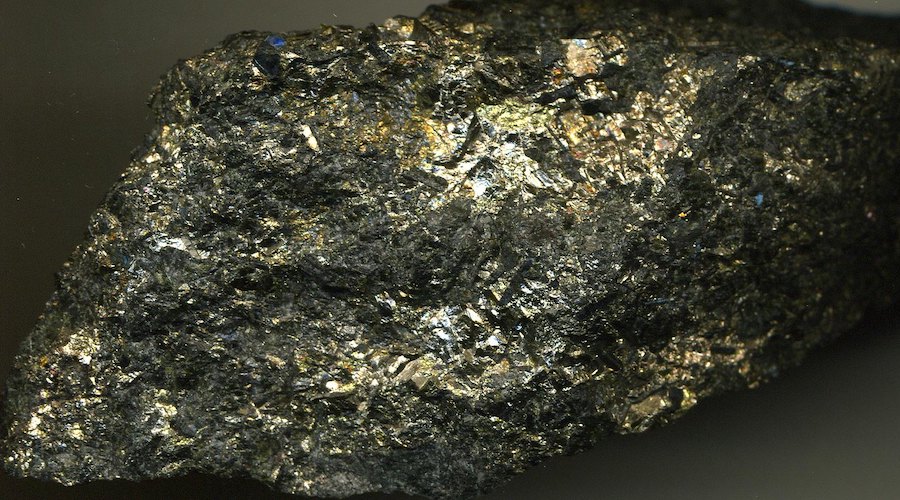

The country is the world’s largest and fastest-growing producer of nickel, used in both stainless steel and electric vehicle (EV) batteries.

It banned the export of nickel ore in 2020, forcing its mining sector to build out processing capacity. The huge flows of ore to China’s stainless steel mills have been replaced by shipments of nickel pig iron (NPI) and ferronickel.

The Indonesian government is now planning to tax exports of both products to stimulate more investment in domestic stainless steel capacity.

However, as stainless and battery nickel processing streams start to converge, it is equally likely the tax will tilt the Indonesian product mix further toward nickel as a battery input.

Exports change after ore ban

Indonesia’s nickel boom was initially defined by China’s hunger for ore to process into NPI as a stainless steel input.

China imported 161,000 tonnes of Indonesian ore in 2006. By 2013 imports had mushroomed to 41 million tonnes.

The following year Indonesia banned ore exports. It partly reversed the ban in 2017, then decided to ban exports again in 2020, this time for good. The policy flip-flop was a source of repeated turmoil in the nickel market at the time.

The export ban has been challenged by the European Union at the World Trade Organization but has achieved its aim of driving a fast expansion of first-stage nickel processing capacity.

China’s ore imports from Indonesia fell to just 856,000 tonnes last year, a figure that may include some misclassified high-nickel-content iron ore.

Imports of Indonesian NPI, by contrast, have surged. In 2014, the year of the original ore ban, China imported 7,000 tonnes of Indonesian NPI and ferronickel, which are covered by the same customs code.

The figure last year was 3.14 million tonnes. The flow accelerated by another 45% to 2.28 million over the first six months of this year.

Although one Chinese operator, Tsingshan Group, has built stainless steel capacity in Indonesia, it’s clear that a lot of Indonesian nickel is still leaving for Chinese mills, albeit in an upgraded form.

Shifting the mix again

Those accelerating export flows have evidently caught the Indonesian government’s attention.

A tax, possibly linked to the nickel price, could come as early as the current quarter, according to Septian Hario Seto, a deputy coordinating minister for maritime and investment affairs.

There is also an ongoing parliamentary review into capping the number of NPI and ferronickel plants operating in the country. There are currently 16 but that number is forecast to rise to 29 in five years, according to mining ministry data.

The government is concerned that too many smelters will use up the country’s nickel reserves too quickly to export what is still a relatively low-value product.

An export tax would be a faster way of stemming the flow of NPI and ferronickel to China, altering again the nickel trade picture between the two countries.

Converging process paths

What’s not in doubt is the Indonesian government’s continued drive to steer its nickel sector further down the value-add chain.

“What needs to be promoted is exports of stainless steel, or at least nickel sulphate,” one of the lawmakers currently studying the NPI capacity question told Reuters.

The comment captures a new truth about Indonesia’s nickel industry.

The processing paths for nickel as a stainless alloy and nickel as a battery input have historically been different, but Indonesian operators are working on closing the gap.

Some are using high-pressure acid leach technology to process ore into mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP), which in turn can be converted into nickel sulphate, the preferred input material for battery-makers.

Others, including Tsingshan, are aiming to achieve the same goal by converting ore to nickel matte in battery-friendly chemistry.

Such is the current scramble for battery material that reduced exports of ferronickel and NPI could simply mean more battery-grade nickel rather than more stainless steel.

Battery tilt

The tilt towards battery products is already starting to show up in Indonesia’s nickel trade with China.

China’s imports of nickel matte have been modest in the past but have quadruped to 55,000 tonnes so far this year. A wholly new flow of Indonesian matte accounted for 41,000 tonnes of the January-June total.

Imports of Indonesian intermediate products, a category that includes MHP, became a regular feature of the two countries’ nickel trade in April last year. Imports totaled 55,000 tonnes in 2021. This year’s January-June count has already reached 156,000 tonnes.

Both products will be refined further into sulphate form for China’s huge battery-manufacturing capacity.

Indonesia would rather China built its batteries in Indonesia and has been actively courting automotive companies such as Tesla with its mineral riches.

Its proposed export tax may hit hardest the flow of stainless-grade nickel to China, but it sets an ominous precedent for the still-incipient export flows of battery products.

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments