Coal’s perfect storm rattles home to $50B new projects

It’s been a tough few weeks for Australia’s coal industry.

First there was a court ruling blocking a new mine on climate change grounds, then one of the world’s largest producers Glencore Plc capped output growth, and finally China was seen to be slowing down Australian imports.

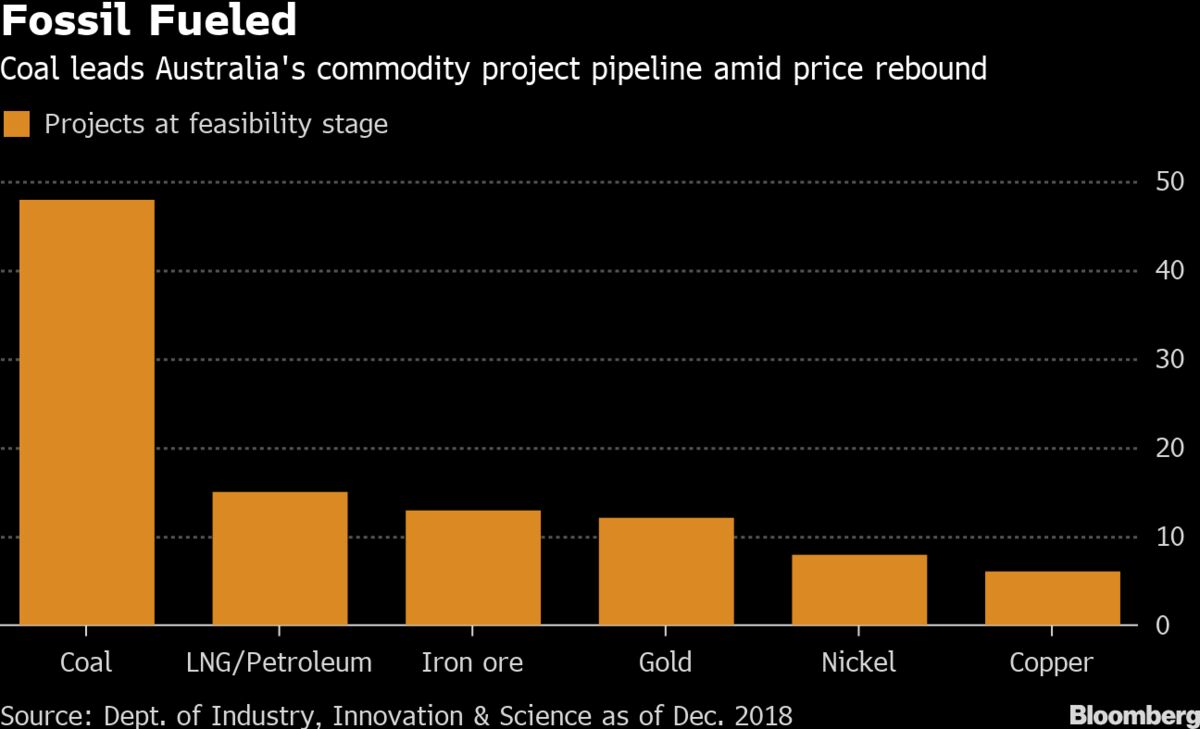

The developments are symptoms of the fuel’s decline and likely signal headwinds for the industry in Australia, the world’s second-biggest supplier of coal used for power generation and steel making, where the government estimates some A$70 billion ($50 billion) of new projects are in the pipeline.

Recent developments should be viewed as part of the fuel’s gradual decline from a position of dominance in the global power mix.

“They’re probably game-changing events from what we once knew of coal,” said David Lennox, a mining analyst at consultancy Fat Prophets. Recent developments should be viewed as part of the fuel’s gradual decline from a position of dominance in the global power mix, he added.

“If you’re building a coal mine and you need to find third parties (to buy the coal), it may not necessarily be so easy, so you’re not going to tip in billions of dollars.”

Of all the shocks to hit the industry, it was perhaps Justice Brian Preston’s ruling in a Sydney court room on Feb. 8 that has the farthest-reaching consequences.

Industry alarm

Gloucester Resources’ Rocky Hill coal mine proposal had already been rejected by the New South Wales government due to its potential adverse impact on the local environment and community, but Preston went a step further in throwing out Gloucester’s appeal, saying it would add to greenhouse gas emissions at a time when rapid and deep cuts were needed.

The minerals lobby reacted with particular alarm to Preston’s judgment that Scope 3 emissions — which encompass the carbon impact from end-users burning the coal — were relevant. The decision would “reverberate across the economy,” Minerals Council CEO Tania Constable said.

The ruling has persuasive power, said Rosemary Lyster, Professor of Climate and Environment Law at the Sydney Law School, part of the University of Sydney. Still, it doesn’t set a binding precedent as it was based on a merits appeal, she said, which doesn’t review the legality of an earlier decision.

“If other cases come before the same tribunal to challenge a decision to allow or not allow a coal mine by way of a merits appeal, the reasoning could go the same way,” she said. It could also influence other tribunals or courts in the future, Lyster added.

Coal may also be an unwitting victim of trade tensions between Australia and China

BHP Group’s Chief Executive Officer Andrew Mackenzie said it was a “strange” notion that Australia could manage climate change by stopping coal production, referring to the Rocky Hill decision.

Potential hurdles

Among the developers wary of the ruling is Whitehaven Coal Ltd. which is currently going through the approvals process for its A$700 million Vickery expansion project. Whitehaven Chief Executive Paul Flynn told investors in February the ruling was “unhelpful,” but did not necessarily have any implications for Vickery.

Other projects that might fall under the spotlight include the Glencore-led United Wambo, which plans to develop an open-cut mine producing up to 10 million tons per annum in New South Wales’ Hunter Valley. The Swiss company bowed to investor pressure when it pledged last week to limit coal production and align the business with Paris climate targets.

That move underlined the pressure producers are under from investors to make climate change an integral part of their business planning. Tougher environmental mandates mean fund fund managers are increasingly steering clear of coal, while Japanese industrial giants Mitsubishi Corp., Mitsui & Co. and Itochu Corp. are all pulling back from the sector.

Coal may also be an unwitting victim of trade tensions between Australia and China with the Asian nation jamming up imports of coal from Australia, with at least one major port suspending customs clearance.

Australia’s coal-loving Resources Minister Matt Canavan is undeterred by recent events, saying he wants the nation to dominate the coal market. Fat Prophet’s Lennox also warns against getting overly bearish on the fuel. While growth in gas, hydro and renewable power generation is set to eclipse coal globally, it will continue to be an important feedstock to meet the energy needs of a fast-growing world population.

(By James Thornhill)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments