Interviewed Tuesday by Tim Loh of Bloomberg News on the sidelines of a Bloomberg New Energy Finance conference in New York, Murray said he might buy coal-fired power plants to secure demand for the output from his privately held mining company, America’s largest:

It’d be the culmination of my life’s work … It’s a new concept. If you control the fuel supply, you can price it how you want it.

A really salient, and related, point, though, is whether anyone wants to buy it at that price. Here, presumably, is where Murray’s plan comes in: If you own the mines and the power plants, then you can have them buy the coal at any price you please.

Except … no. I mean, yes you can. But you really maybe ought not to.

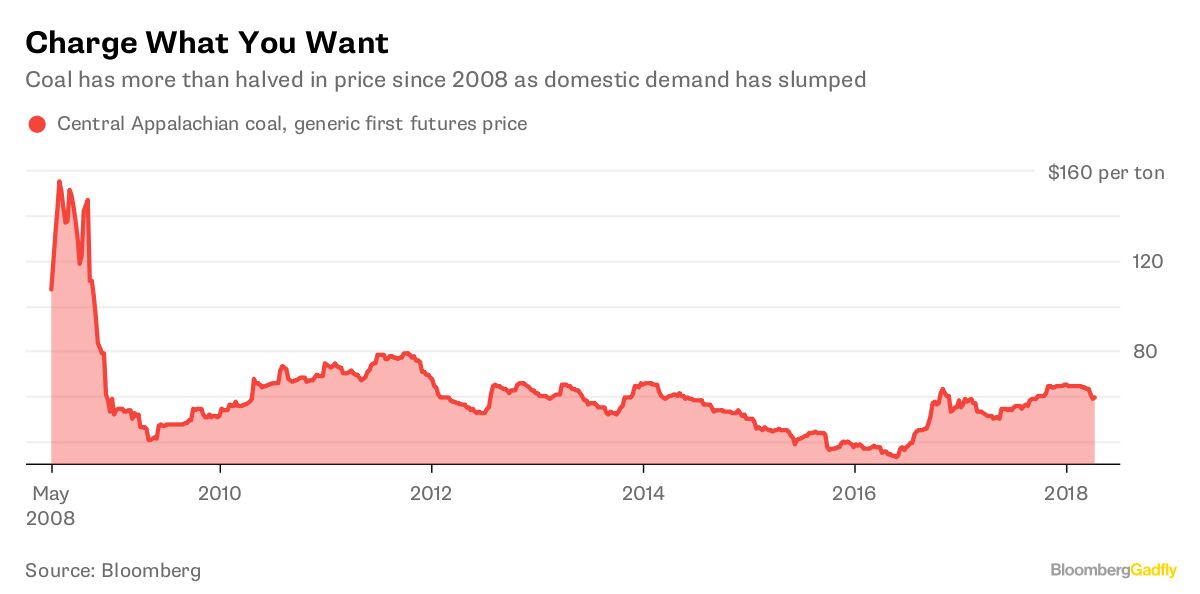

A brief refresher on why Murray contemplates this in the first place. Coal-fired power is falling out of favor in the U.S. at an astonishing rate, squeezed by cheaper natural gas, rising renewable-energy penetration and the cost of dealing with emissions:

In a recent report, analysts at Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimated that half of America’s coal-fired capacity ran with net losses last year. Little wonder that, by 2020, about 72 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity will have closed since “before the election of the Obama administration,” as Murray put it in his prepared remarks Tuesday. Little wonder, too, that Energy Secretary Rick Perry has bent over backwards to secure some sort of regulatory bailout for his boss’s favorite fossil fuel (so far, in vain) and that utility FirstEnergy Corp. recently demanded one to avert the bankruptcy of a coal-heavy subsidiary (again, in vain).

This context reveals the essential flaw in Murray’s plan.

Contrary to what he said, vertical integration by producers of commodities is by no means “a new concept.” The oil industry, for example, has periodically made big investments in logistical, refining and marketing operations to secure demand for its product since the days of Standard Oil (there’s another downstream revival going on now).

However, these tended to make most sense either when they locked up effective monopolies or oligopolies or when oil had yet to penetrate large parts of the globe, allowing the majors to both maintain pricing power and increase volumes. Neither holds true for U.S. thermal coal. Coal consumption is in decline, as is central electricity generation in much of the U.S.

The power sector’s demand for the fuel has dropped 36 percent since 2008 — and not because prices have stayed high:

So while Murray would be free to sell coal at any price to a captive power plant, that wouldn’t make it an economic transaction. Either the mine underprices its coal, and that part of the business suffers, or it overprices it and the already struggling generator goes deeper into the red. The bottom line is that even cheap coal struggles to compete in today’s market, no matter who owns the assets.

Now, it is possible that Murray could buy several plants — probably very cheaply — on the premise that they are due for some sort of revival.

In his prepared remarks, Murray called for regulatory relief, citing a recent study by the Energy Department that said coal plants had played a crucial role in preventing blackouts during the “bomb cyclone” at the start of the year. This echoes the argument made in Secretary Perry’s proposal that was rejected by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Yet the study’s conclusion rests primarily on the fact that more coal-fired power than any other source came online during the cold snap — which is all well and good but also goes to show just how much idle coal-fired capacity there was before the storm hit, demonstrating its lack of competitiveness.

There is a legitimate debate to be had around grid resiliency, but it encompasses a far more complex set of levers including power-market design, efficiency and alternative infrastructure than just subsidizing coal plants.

In any case, if Murray does buy power plants, success wouldn’t rest on transfer pricing. Instead, he would have essentially bought options on regulatory changes and a sustained upturn in U.S. natural gas prices. Good luck with both.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

(Written by Liam Denning)

Comments