A coal miner’s less-is-more lesson for frackers

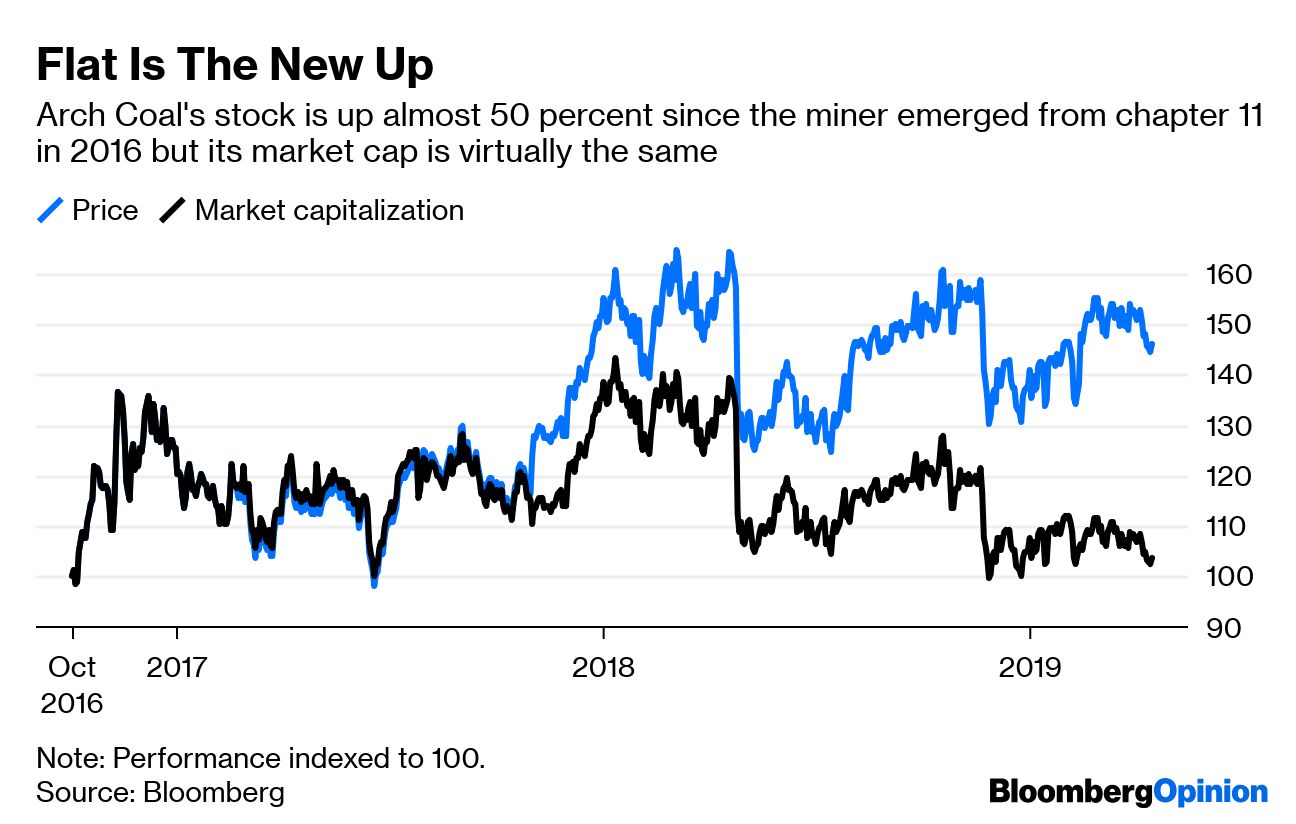

Arch Coal Inc. has a novel approach to beating the market: by not getting any more valuable. The miner’s stock has risen by almost 50 percent since October 2016, when it emerged from bankruptcy. Its market value, however, is roughly where it began.

The variable is the share count. Arch authorized a buyback program in April 2017 and by the end of 2018 had repurchased almost 30 percent of its stock.

It adds up to a compelling return. Say you bought 1,000 shares of Arch for about $68,500 the day before the first buybacks were authorized. Assuming you participated in the repurchases since then, today you would still own almost $64,000-worth of stock. In the meantime, though, you would have pocketed roughly another $25,000 of buyback proceeds and dividends – adding up to a healthy annualized pre-tax rate of return of just over 17 percent.

Arch has been careful to emphasize the higher spending shouldn’t preclude continued payouts to shareholders

Arch likely bought back more of its stock in the first quarter (results are due next week). It had $166 million remaining under its current authorization as of mid-February and consensus forecasts imply $328 million of free cash flow through 2019 and 2020. Taking off some for dividend payments and maturing debt, that would fund enough repurchases at the current price for Arch to have bought in more than 40 percent of the company by the end of next year, relative to where it started.

There’s a good reason for this kind of strategy. The U.S. thermal coal market is so sickly that the White House has been coming up with ever more creative ways to subsidize it. While a fifth of coal-fired power generation has closed since 2012, more than half of the remaining capacity faces negative operating margins at current forward curves, according to analysis released by Bloomberg New Energy Finance earlier this month. And even though the absolute tonnage of coal stockpiled by U.S. power plants has halved since the start of 2016, relative to demand it has barely changed.

Hence, Arch has boosted exports; these generated 45 percent of revenue in 2018 versus just 30 percent the year before. Its reliance on metallurgical coal, the higher-value type used in steel production, has also risen. “Met” coal accounted for almost two-thirds of profits in 2018, up from less than half in 2017, and it’s at the center of Arch’s flagship development project, Leer South in West Virginia. Capital expenditure for Leer South should average about $120 million to $130 million annually over the next few years; a big step-up for a company whose capex overall has averaged about $80 million a year – way lower than depreciation – since emerging from bankruptcy.

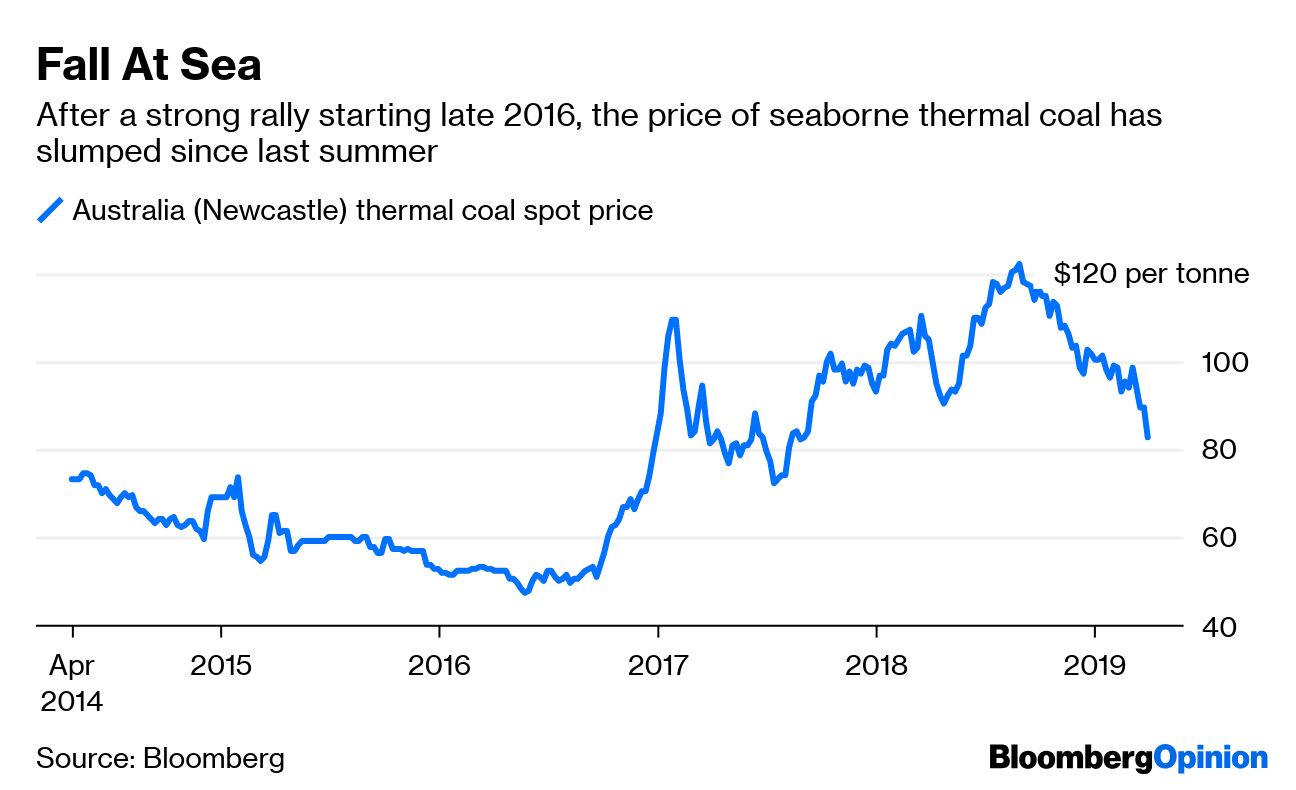

Arch has been careful to emphasize the higher spending shouldn’t preclude continued payouts to shareholders. That is vital. Even the met-coal business can deliver nasty surprises. It contributed to Arch’s big earnings miss in the first quarter of 2018, which touched off a one-day drop of 14.5 percent in the stock. And while exports have helped offset some of the decline in domestic demand for thermal coal, a slump in natural-gas prices – which competes to supply power generation – has had a predictable effect on the coal market.

Facing structural decline in its thermal business and still at the mercy of commodity cycles, Arch’s own stock competes well against development projects for cash. Despite the ups and downs of the past couple of years, the company’s weighted-average return on buybacks to date is 10.5 percent.

Demands for less drilling and more payouts, backed up by activists at times, have become the norm

More importantly, shrinking sends a signal. There is a parallel here with oil exploration and production companies. While oil’s demand dynamics aren’t like coal’s right now, there are intimations of a peak coming, and the sector’s recent history of favoring production volume over value has meant poor returns. Demands for less drilling and more payouts, backed up by activists at times, have become the norm.

Whether drilling or mining, these businesses were defined for decades by empire-building, reasonably reliable growth and the thrills (and spills) of riding the commodity cycle. Acknowledging a less-certain future, or outright decline, and managing accordingly doesn’t come easily. Yet Arch – which did go bankrupt, after all – shows acceptance can bring rewards of its own.

(By Liam Denning)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments